Child Development

Does Your Problem Pup Need a Do-Over?

Rescue dogs with developmental deficits call for creative and mindful solutions.

Posted January 30, 2022 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Rescue puppies can have unexpected and confusing special needs.

- When we understand developmental deficits behind problem behaviors, it’s easier to respond with compassion.

- Early interventions attuned to developmental, social, attachment, and sensory needs may offer hope for problem puppies.

Some years ago, my husband and I adopted a puppy—a fuzzy, potato-sized creature who had been abandoned by her mother behind a gas station.

The first clue that I was unprepared for what lay ahead arrived two days later in the shape of Karyn Purvis, Ph.D., a child development researcher at Texas Christian University. She set her computer on our kitchen table, swung aside long gray hair, and knelt to greet the new addition. Then she asked, “Has she pooped yet?”

“What?” The question startled me.

“Has she pooped yet? She’s so little, her system can’t work by itself. She needs her mamma to lick her belly and help her go.”

“Oh, my goodness,” I said. “Now that you mention it, I don’t recall seeing...”

“Get me a warm washcloth and some cooking oil, and I’ll show you what to do."

Karyn lifted the puppy to her lap and showed me how to stroke its round underside with a warm, moist cloth, mimicking what the mother’s tongue would do. She dabbed a spot of oil on its nose, to be licked off and smooth its digestion.

What a stroke of luck, I thought to myself. This woman was not only a child whisperer—uncannily skilled at connecting with even the most troubled youngsters—she also knew about dogs.

When Karyn returned the next morning to continue our work on manuscript revisions together, she carried a giant tote. Out came a pack of swizzle rawhide sticks for the puppy, plus two gigantic hand-me-down feeding bowls.

I burst out laughing. How would we ever use these monster bowls? Bathe the creature in them? This animal was barely 6 inches long. I thanked Karyn and put the bowls away in a closet, snickering.

But that night, a thought prickled at the back of my head: Did she know something I didn’t?

Apparently so.

Within weeks, I was ranting to my husband.

The puppy’s teeth were too sharp. She was too wild, too nippy, too uncooperative. She rocketed around the house, leaping onto any cat in sight. One of our cats had gone into hiding. The other crouched in ambush, tail twitching, waiting for her chance to—whack!—bring a paw down on the puppy’s head. Our household was in chaos. Visions of Petageddon kept me up at night.

Gone was the sweet, docile little creature we had adopted from the shelter. This animal was mushrooming in size and greeted each day like the crack from a starter’s gun. If I tried to pet her, she sprang and snapped like an angry Jack-in-the-Box. Leashing her for a walk was a whirl of lashing teeth and sharp nails. Red welts laced my arms.

Nothing in the training guides prepared me for a puppy that behaves like a downed electrical wire.

And soon, I snapped.

I rolled a newspaper into a baton and knocked the offender square on the nose. She yelped and backed away, whirling in circles, biting at her tail.

Oh my God, I thought in horror. What have I done? I don’t believe in beating animals.

This could not go on.

I pleaded with my husband to return this handful to the shelter, where somebody more qualified could adopt her.

Naturally, I didn’t mention that a shelter pup’s chances of adoption shrink with each passing day. At nearly 3 months, Hazel was not flashy or photogenic. Even the kind vet described her as “a generic brown dog.” At a shelter, she risked languishing—or worse.

But I was sapped, frustrated, drowning in a river of chaos. My husband and I talked for hours, but ultimately, he could not be swayed. He still believed in her goodness. Each night, after I went to bed, he and the puppy dozed together in front of the television, her snout nestled in his armpit.

Hazel stayed.

Seriously.

What the heck.

When I finally calmed down, the irony washed over me. Here I was—a childless, 40-something woman—being held hostage by a fanged, uncontrollable child. I had become a struggling parent.

And I had just helped write a parenting book.

On a whim, I went to my computer and pulled up the manuscript. The words were familiar, but this evening I read with fresh eyes.

Faint as a wisp of smoke from a genie’s lamp, my co-authors’ compassion and calm and confidence wound around me.

The next morning, when I bent to pet Hazel, she responded with sharp teeth.

“Ow!” I cried. But this time, Karyn’s words whispered in my ear and I curbed my anger. I stepped back. Took a centering breath. Collected myself and gently knelt. The puppy took a break from snapping at her tail to eye me.

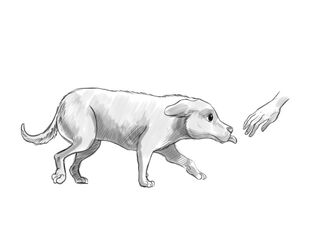

I reached out an arm and extended relaxed fingers in her direction. In a calm voice, I said, “Do over.”

She cocked her head and eyed my fingers. I stayed crouched on the floor and kept my hand steady. I repeated in a mild, warm tone. “Do over.”

Hazel stepped nearer, sniffed, and then—for the first time ever—she licked my hand. No nips, no scratches, no snapping at her tail. One lick. Then she waited and watched.

I nearly swooned with delight.

Good girl! I cooed. Good girl!

* * *

That one lick arrived like a miracle, a clear sign of goodwill.

In a flash, I saw that this puppy wasn’t the devil’s spawn or a malicious sprite out to torment me. Hazel was a young, unformed creature who didn’t understand what was expected of her. She wanted to connect with us, her clan, her human pack. She just didn’t know how.

That do-over cast my role in a new light. More than simply feed her, care for her physical needs, or string safety barriers across the house to protect her from injury, I needed to become this animal’s guide, her teacher, her coach. This puppy and I didn’t have to be adversaries. It was time for a fundamental shift in my attitude.

In my ignorance, I assumed life with a puppy would be a straight trajectory, an easy transition to maturity. After some rambunctious chewing and piddling, the animal would transform directly into a docile family pet. Neat. Simple. Straight line. No zigs or zags.

It hadn’t dawned on me that a rescue puppy who had introduced herself by climbing into my husband’s lap and going to sleep might be waving a red flag of malnutrition or illness. That her early inability to move bowels might be a sign of developmental or sensory needs. That being taken too soon from her biological family would deprive her of basic social skills. That her small size could signal an early stage of life and trauma and medical problems rather than her final, mature stature—which eventually peaked at 65 pounds, more than double what we guessed.

No, it hadn’t crystalized yet that we had a special needs puppy on our hands when I revisited The Connected Child and was inspired to offer the puppy a re-do, a mulligan, a do-over.

But this single interaction affirmed the promise my husband saw in her. It offered hope that I, too, could one day bond with this challenging puppy. And with my shift in mindset, I could explore creative ways to help Hazel settle and adjust. Over time, she became a loving family member who grew old peacefully with our two cats.

What made the “do-over” strategy work?

I asked Kelley Bollen, a certified animal behavior consultant and former director of behavior programs for the Maddie’s Shelter Medicine Program at Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. She told me:

“What you call the 'do-over' was just so great because you came to a place where you knew you had to change. It wasn't about the puppy changing, it was about you changing. You finally realized, look, this is a baby. This is an infant. This is what I try to teach people: you are a grown adult human. This is an infant animal, and it's doing puppy things. If you want to teach it, you have to guide it and be patient with it.

“Your ‘do-over’ worked because the puppy was still weeks old and very young. You were lucky because you made this decision when the puppy was still open to learning. If the puppy was too much older, it wouldn’t have been as receptive.

“You also learned from your own experience that your demeanor is going to affect the animal's demeanor. This is true when I work with clients who have a dog who shows aggressive behavior and we're trying to modify the aggressive behavior. Part of my work is to teach them how to change their attitude and emotions and behavior so that they're not inadvertently feeding right into what the dog's doing. You were feeding into the puppy. You were feeding into the puppy's mouthiness and inability to calm down because you were getting so agitated by it. Your energy was feeding her energy, and it was just this horrible cycle you were in. When you finally realized, 'I'm going to take a breath, I'm going to calm down, I'm going to be quiet and calm with this puppy,' the puppy in turn was able to do the same.”

It's easy to misinterpret dog behavior. Here are some examples.

(c) Wendy Lyons Sunshine. All rights reserved.

References

Purvis, K. B., Cross, D. R., & Sunshine, W. L. (2007). The Connected Child: Bring Hope and Healing to Your Adoptive Family (1st edition). McGraw-Hill Education.

Purvis, K. B., Cross, D. R., Dansereau, D. F., & Parris, S. R. (2013). Trust-Based Relational Intervention (TBRI): A Systemic Approach to Complex Developmental Trauma. Child & Youth Services, 34(4), 360–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2013.859906

Bollen, K. S., & Horowitz, J. (2008). Behavioral evaluation and demographic information in the assessment of aggressiveness in shelter dogs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 112(1), 120–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2007.07.007