Relationships

How Close Do You Really Need to Get to Your Partner?

Why partners may struggle to find the "Goldilocks Zone."

Posted February 25, 2022 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- In general, the closer a couple feels to each other, the happier they are in their relationship.

- However, more isn’t always better, and different people need different degrees of closeness with their partner.

- Couples are happiest in the “Goldilocks Zone”—neither too close nor too distant from their partner.

For much of human history, marriage was an economic arrangement for maintaining property and raising children. People wanted a partner they could depend on to fulfill their end of the bargain, but they had little expectation of getting emotionally close to their spouse. Instead, they got that through relationships with friends and family members.

Nowadays, though, we expect our partner to be our soulmate, the one person in our lives who fulfills all our needs, whether that be sex, companionship, or emotional support. This means that intimate couples generally feel a need to be emotionally close to their partners, with expectations that the two of them should act and feel like one, or that they should be able to read each other’s thoughts and feel each other’s emotions. But how close do you really want to be to your partner?

Most research on this topic to date has been conducted with the assumption that the closer a couple is, the happier they will be in their relationship. Data show that people who feel close to their partner tend to be more sexually and relationally satisfied. However, as University College London (UK) psychologist David Frost and San Francisco State University psychologist Allen LeBlanc point out in an article they recently published in the Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, the connection between closeness and the quality of romantic relationships is complicated.

Closeness as the inclusion of other in self

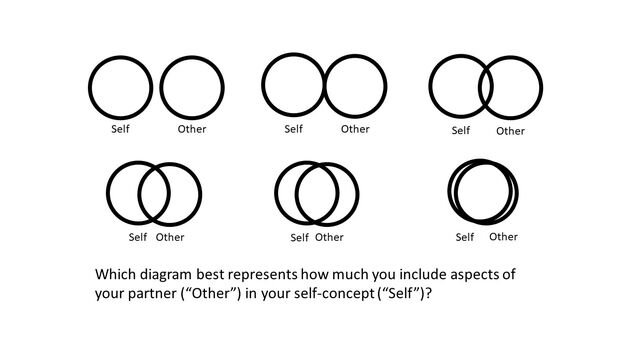

Because the term “closeness” is vague, in that you can be physically close but emotionally distant or vice versa, relationship scientists define the term as the degree to which your own self-concept includes aspects of your relationship partner. This is referred to as “inclusion of other in self,” or IOS for short.

In the laboratory, IOS is measured with a simple task involving two circles, one representing yourself and the other your partner. To show how close you feel to your partner, you select the degree of overlap between the two circles that best represents the inclusion of your partner’s characteristics in your own self-concept.

Using this IOS scale, researchers have found that the closer people feel toward their partner, the greater their relational and sexual satisfaction as well as the stronger their commitment to the relationship. This finding meshes with the modern romantic view of marriage, in which the two partners become as one and serve as each other’s soulmates.

More isn’t always better

However, this “more is better” approach often fails in other areas of relationship research. Take sexual frequency and relationship satisfaction as an example. Plenty of research shows that, in general, the more often a couple has sex, the happier they are with their relationship. Yet, a closer look at the data shows that what’s really important is whether couples are getting as much sex as they want. When researchers ask couples to report both actual and desired frequency of sex, what they find is that the less discrepancy there is, the higher their level of sexual and relationship satisfaction.

Likewise, Frost and LeBlanc propose that it’s not actual closeness, but rather closeness discrepancy, that predicts the quality of the relationship. In other words, people are happiest with their partners when their desired degree of closeness matches their actual experience. In other words, they’re satisfied with their relationship because they’re as close to their partner as they want to be.

The researchers point out that closeness discrepancy can occur for two reasons. One is that people don’t feel as close to their partner as they’d like, in which case they see too much distance in the relationship. The other is that they feel closer than they want, in other words, not enough distance. Either way, closeness discrepancy can put a damper on a relationship.

Frost and LeBlanc also speculated that feelings of closeness discrepancy in one partner can also affect the relationship satisfaction of the other partner. This is because emotions are contagious, and stress can spill over from one person to another. In this way, the second person picks up on the low mood and high stress of the first partner, and they both feel less satisfied with the relationship as a result.

Finding the “Goldilocks Zone”

To test these hypotheses, the researchers recruited 103 cohabiting couples to respond to a survey, with each partner completing the questionnaire separately. First, each partner indicated both their actual and desired degree of closeness, using the IOS scale. Next, they responded to questions that assessed their relationship satisfaction, sexual satisfaction, and degree of commitment to the relationship.

Frost and LeBlanc calculated closeness discrepancy for each partner by subtracting desired from actual closeness. Approximately 59 percent of respondents reported no closeness discrepancy, about 35 percent reported that they weren’t as close as they’d like to be, while around 6 percent said they were closer than they wanted.

The researchers also compared each person’s desired and actual degree of closeness with those of the other partner. They found that in more than half the couples, there was a discrepancy between one participant’s actual closeness and their partner’s desired closeness.

When they compared each participant’s closeness discrepancy with their ratings of relationship satisfaction, sexual satisfaction, and commitment, they found, as predicted, that the greater the closeness discrepancy, the lower each of these three measures of relationship quality was. In other words, it’s not necessarily the degree of closeness that predicts relationship quality but rather whether each partner’s closeness needs were getting met that counts. The researchers also found a “partner effect” for closeness discrepancy, in that when one partner’s closeness needs weren’t being met, the other partner also reported somewhat lower relationship quality.

Modern views of marriage often portray it as a melding of minds in which two become one. This “soulmate relationship” works well for some couples, but findings from the current study as well as plenty of others show that it isn’t necessarily a goal that all couples should strive for. Instead, couples are happiest when they find themselves in the “Goldilocks Zone” of getting their needs met to just the right amount. And they’re even happier still when they strive to meet their partner’s needs, whatever those may be.

Facebook image: fizkes/Shutterstock

References

Frost, D. M. & LeBlanc, A. J. (2021). The complicated connection between closeness and the quality of romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. Advance online publication. DOI: 10.1177/02654075211050070