Health

The Mental and Physical Health of Caregivers

How do we safeguard the health of caregivers?

Posted February 22, 2019 Reviewed by Davia Sills

In a 2017 Health Affairs piece, Peter Buerhaus, David Auerbach, and Douglas Staiger discussed an approaching health care challenge—the reality that many nurses of the Baby Boomer generation will soon retire, creating a shortage of experience among the remaining RN workforce.

The article caused me to reflect on the broader condition of caregivers in the U.S., particularly that of non-professional caregivers, who face many of the same scenarios that confront professional nurses but must do so without the training and expertise of the experienced RNs who will soon leave the health care field. As these caregivers play an ever-greater role in safeguarding the health of our aging population, here's a note on the physical and mental health of caregivers, and how public health can best support these individuals and, by extension, the populations they care for.

As I have written before, population aging is one of the central demographic shifts of the coming century and a key challenge for public health. The Population Reference Bureau projects that, by 2050, the total global population of people who are over the age of 65 will comprise 16 percent of the world’s population—nearly 1.5 billion people. This shift represents a dramatic increase since 1950 when people over the age of 65 totaled just 5 percent of the global population.

In the United States, the number of Americans aged 65 and older is expected to more than double between 2016 and 2060, from 46 million to more than 98 million, as the proportion of the 65+ age group rises from about 15 percent to about 24 percent of the world’s population. Aging populations face a range of distinct health challenges, from chronic disease to issues of mobility and mental health. Increasingly, the work of helping these populations navigate the challenges they face has been performed by unpaid caregivers, i.e., family or friends who provide full-time or part-time assistance to individuals with an illness or a disability due to age or other factors. Because caregivers must often balance their work with other day-to-day responsibilities, providing care can take a toll on their well-being.

There are over 34 million unpaid caregivers working in the U.S. who provide support to an adult aged 50 years or older in their life who suffers from an illness or a disability. Eighty-three percent of these are family caregivers assisting a relative. Approximately 21 percent of U.S. households play host to this type of support, and unpaid caregivers provide approximately 90 percent of long-term support.

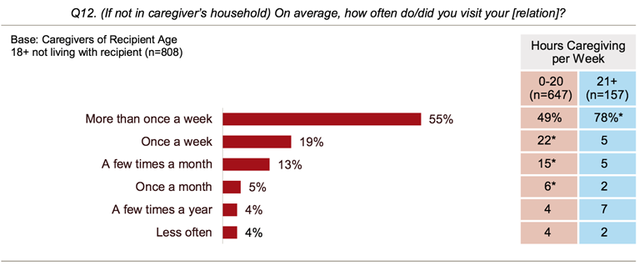

The “typical” caregiver is 46-years-old, female, works outside the home, and devotes over 20 hours per week to providing unpaid care to her mother. Many of those who care for older individuals are older themselves; the average age of caregivers supporting someone 65 or older is 63. Often, caregivers live close to the person they support; of the 83 percent of caregivers who care for relatives, 24 percent live with the person they care for, 61 percent live up to an hour away, and 15 percent live between one and two hours away. Fifty-five percent of caregivers who do not live with the care recipient say that they visit the care recipient more than once per week (Figure 1).

The financial costs of caregiving can be significant. In 2007, the out-of-pocket expense for individuals caring for someone 50+ was $5,531. These costs can be compounded by a loss of time; caregivers must often minimize other important activities to continue to provide support.

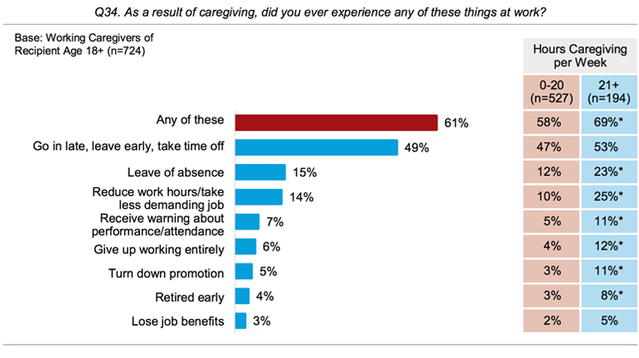

An estimated 37 percent of those providing care for someone 50+ in 2007 needed to cut back on work hours or even quit their job. This is particularly significant, as most caregivers are employed; approximately 60 percent of caregivers between the ages of 50 and 64 work either full-time or part-time. Forty-nine percent of employed caregivers have said that they needed to either arrive to work late, leave early, or take time off as a consequence of providing care; 15 percent have said that they needed to take a leave of absence (Figure 2).

Providing regular support to a friend or a relative can entail a number of responsibilities, which, taken together, can create stress and undermine the health of caregivers. Increased life expectancy and better management of chronic care, both positive developments, have nevertheless lengthened the period of commitment for caregivers, affecting their quality of life over the long term. The responsibilities of care can include meal preparation, cleaning, running errands, helping the care recipient dress and take medication, scheduling appointments, providing transport, and assisting with physical therapy.

The intensity of this workload depends in large part on the conditions surrounding the care recipient. The recipient’s distance from the caregiver, illness type, and geographic/cultural context all play a role in shaping the caregiver’s experience and her or his health. Caregivers have, for example, reported skipping doctor’s appointments, with 57 percent saying that they prioritize the care recipient’s needs over their own. Fifty-one percent say that they do not have enough time to take care of themselves, and 49 percent say that they do not do so because they are too tired. Additionally, 29 percent say that they experience difficulty managing emotional and physical stress.

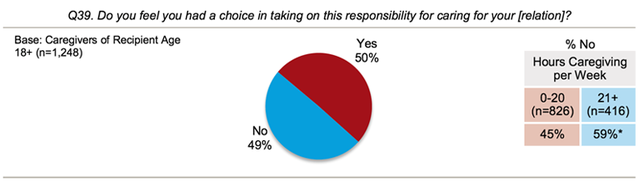

Caregiving can also pose challenges to mental health. Significantly, 49 percent of caregivers said that they do not feel that they had a choice in taking on their responsibility (Figure 3).

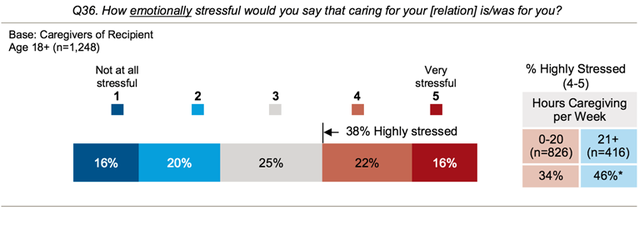

Given the challenges of caregiving and the fact that it often comes as an unsought responsibility, it is perhaps not surprising that four in 10 caregivers say that they consider their caregiving activities to be highly stressful, with 38 percent ranking their stress level as four or five on a five-point scale (Figure 4).

Caring for someone with a chronic or long-term physical or mental health condition appears to be particularly stressful for caregivers. Fifty-three percent of caregivers supporting someone with a mental health issue, 50 percent supporting someone with Alzheimer’s disease or some other form of dementia, and 45 percent of those supporting someone with a long-term physical condition report feeling emotional stress. This stress has been associated with the level of suffering that the caregiver perceives in the care recipient, with emotional and existential distress significantly linked with rates of caregiver depression and the use of antidepressant drugs.

It is important to note, however, that caregivers also cite the positive elements of caregiving. Even when the experience becomes stressful and intense, caregivers will say that it provides meaning, gives them an opportunity to learn new skills, strengthens their relationships with other people, and makes them feel good about themselves.

Safeguarding the health of caregivers means investing in long-term, community-based care delivery systems, and technological innovations like telemedicine, that shift the burden of care away from individuals and towards the social and economic resources that we can, collectively, provide. Too often, age and disability mean isolation; we need to work to change this, so that individuals become more, not less, integrated into the community as they age.

A public health approach stands to improve how we care for those with chronic disabilities in older age and lift the burden off their caregivers. This means investing in much more than clinical care, broadening our investment to include exercise programs, home visits, volunteer opportunities, and other means of engagement. At the level of prevention, we can make a difference by tackling the conditions that lead to chronic disease and mental health challenges, investing in the foundational determinants of health to mitigate these conditions throughout the life course.

Ultimately, caregiving emerges out of love and commitment to family and our intimate circle of community members, reflecting the broader social bonds that tie all of us together and helping to create a society that is worth living in. Improving conditions for caregivers means deepening these bonds and the capacity of communities to provide support for populations who need it. As we make progress in this area by strengthening communities, we must also keep the focus on the caregivers themselves, working to support their physical and mental well-being.

For those of us who, like myself, have loved ones acting as caregivers or who are caregivers themselves, this is more than an academic question; it is a personal one. As populations age and the need for caregiving grows, public health stands to play a key role in making sure that both caregivers and care recipients are supported at all stages of life.