Career

How to Overcome Regret

“The hardest part was not the decision but coping with the ‘what if’ afterward."

Posted November 29, 2019 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Many people nearing the end of their lives battle feelings of regret. This negative emotion refers to self-blame resulting from the evaluation of bad life choices and the comparison with counterfactual scenarios of “what could have been.” Long-term life regrets frequently result from missed opportunities such as not enough time spent with friends and family or the failure to pursue the career path of one’s choice.

Anticipated Regret

The emotional pain associated with regret can be a key factor in shaping future life choices, and studies have demonstrated that the mere expectation of regret (also referred to as “anticipated regret”) can have a powerful impact. For example, an experimental study of bidding behaviour in first price auctions showed that participants were more likely to overbid if they anticipated the regret of losing to another person’s offer.

This insight on anticipated regret finds frequent application in aggressive sales strategies, which invoke “FOMO” (fear of missing out) during limited time offers to trick people into buying items they don’t need. Ever feel your purse strings loosening when spotting signs that promise a “one-time only deal” and urge you to “act fast to avoid missing out”? If so, heightened levels of anticipated regret might be the reason.

Indeed, research further suggests that anticipated regret is often disproportionate and may be worse than actual regret. In a study of emotional responses in the context of a negotiation task, for example, participants were found to overestimate the regret they expected to experience compared to the regret they actually reported in case of a negative task outcome. It thus appears that many people suffer unnecessarily from the negative affect associated with anticipated regret.

Minimising Regret

The above examples highlight situations where anticipated regret may create a disadvantage for decision makers. This is particularly detrimental in cases where personal choice has little effect on the final outcome and regret is unlikely to improve future decisions. In the negotiation study, for example, participants (unknowingly) interacted with a computer agent who had been programmed to reject their negotiation offer independent of its size. In situations like this—characterised by predetermined outcomes and little personal influence on the result—any self-blame for the outcome would be futile.

To minimise negative feelings of regret, many people try to reduce the riskiness of their choices. But is this really the best approach? Let's take a look at an alternative strategy referred to as the Minimax Regret principle.

As an example, consider the difficult task of making a career choice. A person (let’s call her Sandy) is torn between two different job choices: She could either accept a safe public-sector role, which would guarantee her a stable income no matter the overall economic developments. Her second option is to run her own business as a self-employed yoga instructor, which has been a life-long dream, but holds obvious risks. How can she minimise regret associated with her final career choice?

A Formal Analysis

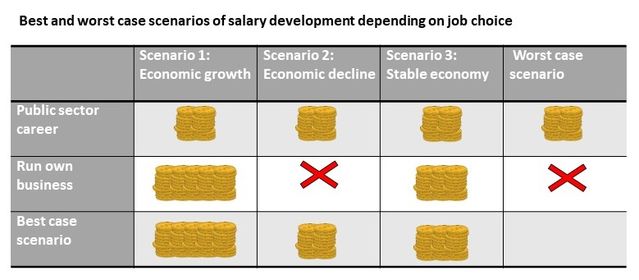

To compare the two choices, Sandy decides to draw up a table and fill the cells with rough estimates of her future income given three possible economic developments: (1) economic growth, (2) economic decline and (3) a stable economy. Take a look at Table 1, which displays the different income scenarios: The bigger the stack of coins, the higher the salary! Sandy knows the public sector job has a fixed salary. Hence, no matter the economic situation, she’d always earn a decent wage. On the other hand, while her yoga studio has the potential to generate a lot of income in a growing economy, bankruptcy is an all-to-real possibility in case the economy declines.

If Sandy was merely interested in minimising risk, her best bet would be to pick the public sector job. However, let’s assume she’s also interested in reducing feelings of regret. Maybe she is worried about waking up one day feeling disappointed with life’s missed opportunities!

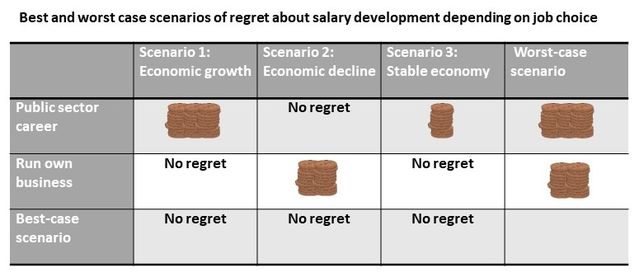

Consequently, Sandy drafts another table based on the first. In this second table, she considers the worst-case scenarios of regret. Sandy does this by looking at each scenario column in Table 1 and calculating the difference between each career’s salary and the best possible outcome for that scenario. For example, assuming economic growth, running her own yoga studio would give her fantastic earnings, which are also her best possible outcome in the situation. Hence, the choice of running her own business in Scenario 1 would incur no feelings of regret. However, if she had chosen the public sector career in a growing economy, she probably would have been disappointed by the small salary compared to the alternative income from the yoga studio. Sandy depicts this anticipated regret using three darkened coin stacks in the first cell of the second table. This way she systematically continues her analysis until all cells are filled.

Considering the final column of Table 2, Sandy can now draw some overall conclusions about the worst case scenarios of regret. The results surprise her: Even though the public sector job is arguably the less risky job choice, her analysis predicts overall higher levels of regret associated with this choice. Sandy is glad she has completed this little exercise—it appears that choosing the career path of a self-employed yoga teacher will leave her feeling happier with her earnings in the long-run!

Do I Really Need Tables?

The Minimax Regret approach is a structured process that can help people to think about future regret. However, not every decision situation requires a formal analysis of this kind. Often, a balanced consideration of different outcomes and your likely feelings associated with those outcomes can be enough to help you make a choice and minimise future self-blame or regret. By developing awareness for the power of regret and improving accuracy of anticipated regret, you can take an important step towards reducing later disappointment in your choices.

Because, to put it in the wise words of an anonymous Twitter user: “The hardest part was not the decision, but coping with the ‘what if’ afterwards.”