Forgiveness

Forgiveness

Is good for your health - physical, psychological and spiritual.

Posted June 11, 2018

Coventry is an attractive city well-known for its strong associations with forgiveness, reconciliation and peace. It was therefore an ideal place for the recent three-day conference on Forgiveness, held jointly by BASS (the British Association for the Study of Spirituality) and the European Conference on Religion, Spirituality and Health.

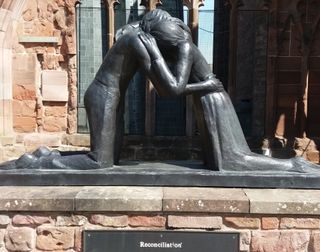

Nearly two hundred delegates attended the university site, just walking distance from the bombed-out shell of the old cathedral, destroyed during a Nazi air-raid in November 1940, and the adjacent new cathedral, completed in 1962. Notices, plaques and monuments, including the evocative 'chapel of unity' inside the new building, and the poignant statue 'Reconciliation' among the ruins, bear powerful witness to the quietly persevering efforts of many individuals and organizations forever seeking to build peace and security throughout the world today.

Despite the academic nature of the event, many moving stories were told at the conference, often involving the most extreme provocation. For example, in his public lecture on 'Dimensions of Forgiveness', Professor Everett Worthington from Virginia revealed that, despite being an expert on the subject, when his elderly mother was attacked and killed in her own home by a night-time intruder, his first impulse was to 'pulverise him to death with a baseball bat', before later calming down and wisely begin putting into practice what he had been teaching others for many years. 'Forgiveness', he said, 'Can be a valuable turning point in life'. Worthington's comment was echoed by numerous speakers, and other recurrent themes included:

- Forgiveness as a universal phenomenon, cutting across many different philosophies and religions.

- It is normally thought of as the one receiving harm forgiving someone causing the harm, but self-forgiveness can also be important, also (for some) forgiving and/or being forgiven by God.

- A process of reflection is involved.

- It requires an aspect of generosity, of giving a gift.

- Forgiveness does not mean making excuses for the perpetrator of harm.

- It does not mean abandoning the search for justice and restitution.

- It does not require repentance, remorse or the wish to be forgiven by the perpetrator, who may actively avoid or reject forgiveness;

- However, when an apology is forthcoming, it makes reconciliation much easier.

- Overcoming self-blame by forgiving oneself, and the forgiving of others, both benefit one's health.

- This may be because anger (sometimes in the form of a kind of toxic rage) is often repressed and can compromise health, for example by contributing to an increased risk of cancer. It can also damage existing relationships and make successful new ones harder to form.

- Forgiveness interventions and therapy can cure unhealthy anger.

- People studied and found to have benefited include incest survivors, people undergoing drug rehabilitation, cardiac patients, emotionally abused women, people who are terminally ill, and elderly cancer patients.

According to conference speaker, Robert Enright (known, according to Time magazine, as 'the forgiveness trailblazer'), there are four phases in the process of forgiveness:

Preliminaries - clarification

Who hurt you? How deeply? A specific incident to focus on? What were the circumstances? What was said? How did you respond?

Phase 1: uncovering anger (also shame, guilt etc.):

Have you been obsessed about the injury or the offender?

Do you compare your situation with that of the offender?

Has the injury caused a lasting change in your life?

Has the injury changed your worldview?

Phase 2: deciding to forgive:

Decide that what you have been doing hasn't worked.

Be willing to begin the forgiveness process.

Decide to forgive. Start by committing to do no harm to the one who hurt you.

Phase 3: working on forgiveness:

Work towards understanding (including personal, global and cosmic/spiritual perspectives).

Work towards compassion.

Accept the pain.

Give the offender a gift.

Phase 4: discovery and release from emotional prison:

Discover the meaning of suffering

Discover your need for forgiveness

Discover that you are not alone

Discover the purpose of your life

Discover the freedom of forgiveness

For some people, a useful approach involves writing a letter to the perpetrator, not to be sent, but as a way of clarifying and expressing one's feelings, enabling the trans-formative process of reflection.

Enright then spoke about a programme of 'Forgiveness Education', which, through stories, introduces students to the idea of forgiveness with no pressure to forgive. Already successfully deployed in 18 US states, Canada, Mexico, 8 countries in Africa, 5 countries in Asia, 7 countries in Europe, 4 countries in the Middle East, and 2 countries in South America, the initiative continues expanding. It involves 1 hour per week for 12 - 17 weeks, delivered by a teacher or mental health professional.

Forgiveness education shows young people how story characters solve problems, helping them understand what kindness, respect and love are when someone has been treated unjustly, enabling them, in the safety of their home or classroom, to practice forgiveness before the big storms of adult life arrive. Outcome measures show that forgiveness education reduces anger in students, increases co-operation in classrooms, and can improve academic achievement.

The strong link between forgiveness and spirituality was made clear on numerous occasions at the conference, for example in a study by psychiatrist Gloria Dura-Vila of five novice Roman Catholic nuns sexually abused by priests, people they had trusted. Their responses and recovery patterns were full of similarities, moving over time through a series of identifiable stages from severe physical, psychological and spiritual distress to their current state of mental well-being and spiritual balance. (N.B. Only nuns who had lived successfully through this kind of trauma were surveyed. Those who left the Order were not investigated.) Helpful factors included healthy grieving associated with spending lengthy periods in prayerful meditation ('I cried and prayed'), eventual disclosure within their religious community of what had happened, followed by continuing acceptance and support from their peers and superiors. Forgiving those responsible and praying for them was also an important aspect of spiritual re-integration. All five described 'post-traumatic growth', saying that they were now more in touch with human nature and sexuality, and with everyday reality.

The final speaker, Professor Carlo Leget, described a study of nurses, working with dying patients, who described occurrences of 'peaceful deaths' following acts of forgiveness and reconciliation as 'miraculous'. The whole conference affirmed for me that it is good to forgive, a wonderful, healthy, healing thing... and this last talk served to remind us that it is never too late!

Copyright Larry Culliford

Watch Larry on You Tube in a series of short videos on 'spirituality.

His new book, 'Seeking Wisdom - A Spiritual Manifesto', has already gathered superlative praise. See his website for more information about this and Larry's other influential publications.