SSRIs

Antidepressant Guidelines to Tighten in the UK

Welcome policy change also reveals scale of the problem.

Posted May 31, 2019

Doctors across Britain will soon be told to warn millions of patients taking antidepressants that ending treatment can cause “severe” adverse effects and last much longer than previously advised.

“We are currently updating our guidelines on the diagnosis and management of depression in adults,” a spokesman for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) told a reporter for the Daily Mail midweek. The newspaper called it a “major U-turn” in policy. After months of reporting by British media on the scale of the problem, with more than 7 million in Britain taking antidepressants (one of the highest per capita among OECD countries), the Royal College of Psychiatrists warned that the effects of ending treatment can, in fact, be “severe” and last for weeks, even months.

Current guidelines from NICE, a watchdog for the National Health Service, state that “[withdrawal] symptoms are usually mild and self-limiting over about 1 week.” “For the vast majority of patients,” the RCP until recently held, “any unpleasant symptoms experienced on discontinuing antidepressants have resolved within two weeks of stopping treatment.”

A substantial number of international studies and meta-studies have disputed both assertions, leading last month to a joint statement in the British Medical Journal by leading UK, European, and North and South American researchers: “Clinical guidelines on antidepressant withdrawal urgently need updating.” “We think that NICE's current position on antidepressant withdrawal not only was advanced on insufficient research but is now widely countered by subsequent research.”

Britain’s regulators were issuing recommendations at odds with a now-substantial evidence base, they concluded, arguing that antidepressant withdrawal too often was “misdiagnosed … as relapse or as a failure to respond to treatment—with antidepressants being reinstated, switched, or increased in dose as a result.” That would help explain, they wrote, “why the average time a person spends taking antidepressants has doubled in the UK since the guidelines were introduced in 2004.”

One 2010 study from Japan found that 78 percent of people trying to taper off Paxil experienced severe withdrawal symptoms. Last September, London-based researchers James Davies and John Read received global coverage when they concluded, based on a meta-study of 23 earlier peer-reviewed studies, that “more than half (56 percent) of people who attempt to come off antidepressants experience withdrawal effects.” Further, almost half of them (46 percent) described the effects as “severe.”

In a March 2019 article on antidepressant withdrawal for the New York Times, Benedict Carey added, “Dutch researchers in 2018 found that 70 percent of people who’d had trouble giving up Paxil or Effexor quit their prescriptions safely by following an extended tapering regimen, reducing their dosage by smaller and smaller increments.”

The same month, Lancet Psychiatry published a study by University College London psychiatry researchers Mark Horowitz and David Taylor, arguing that responsible tapering of antidepressants should extend to months or even years, depending on the individual, not conclude in four weeks, the boilerplate advice. Both authors added that their recommendation stemmed in part from their own difficulties trying to end antidepressant treatment, which Taylor described in a related New Yorker article as a “strange and frightening and torturous” experience that he endured for six weeks.

Even though the Royal College of Psychiatrists “now accepts that it has not paid enough attention to patients suffering from severe withdrawal symptoms when coming off antidepressants,” wrote Guardian columnist Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett of the recent shift in policy, “patient stories weren’t enough to bring about change to prescribing and withdrawal guidelines. That has happened only because clinicians such as Taylor, who also happened to be a patient, have experienced withdrawal and studied it as a result.” Had he not suffered withdrawal, Taylor told the New Yorker, he “probably would have accepted the standard guidelines.”

Doctors for years “have dismissed or downplayed such symptoms,” Carey concluded in the New York Times, “often attributing them to the recurrence of underlying mood problems.” Drug-makers also helped minimize the problem by urging staff and publicists in internal memos, “Highlight the benign nature of discontinuation symptoms, rather than quibble about their incidence.”

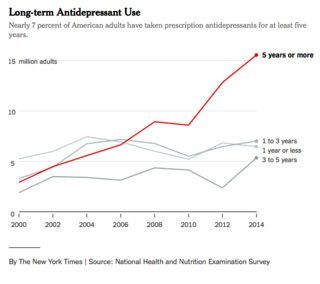

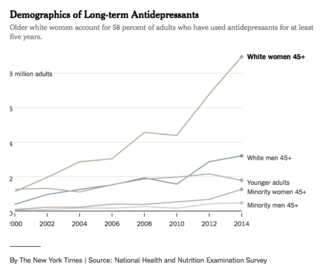

With all the evidence now amassed, the decades’ long delay in updating prescribing guidelines for such widely prescribed medication raises urgent questions about a profession-wide failure to recognize the scale of the problem. “More than 15 million Americans have taken the medications for at least five years,” notes Carey, “a rate that has almost more than tripled since 2000,” according to a New York Times analysis of federal data.

“I know antidepressant withdrawal symptoms are real,” concludes Cosslett pointedly of her own difficulties ending treatment. “Why didn’t doctors?”