Identity

Clothes Make the Killer

Some killers dress the part, influencing thoughts, acts, and identity.

Posted November 29, 2020

We’re aware of murder kits that some offenders prepare so they can more effectively carry out their crimes. We rarely consider their clothing. Yet some killers do consciously dress for murder. They even refer to certain outfits as their “kill” clothing. This “enclothed cognition” apparently helps them to feel more like a someone intent on taking a life.

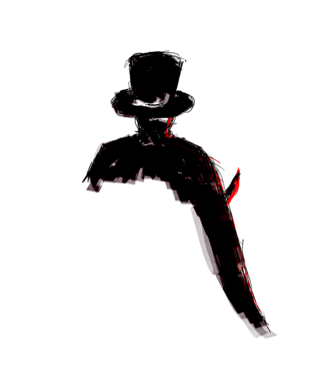

Imagine Jack the Ripper getting ready for a fatal prowl. We don’t really know if JtR was a he, she, or they, but an image persists of a man stalking in an opera cloak, the better to hide his implements of death. This conveys the impression of a killer from the upper class, someone who could afford such a cloak and enhances the secretive nature of the sinister man who slaughtered sex workers undetected.

So, what do the killers say? When Edmund Kemper was arrested after killing his mother and her best friend in 1973, he admitted to the murders of six hitchhiking coeds. For hours, he described to detectives how he’d met the young women and what he’d done to them.

He blamed his mother’s emotional abuse. A motorcycle accident had forced him back home with her, and her constant belittling had enraged him. After arguments, he’d cruise around to watch the college girls she said were too good for him. When they’d thumb for rides, he’d pick them up. Soon, he’d packed a murder kit with knives and bindings. He’d worn a special outfit, reserved for murder: a pair of dark jeans, a buckskin jacket, and a tan checkered shirt. They’d reminded him he meant business.

The idea that “clothing makes the man” is based on the psychology of impressions. People dress “up” to enhance their status and make others think they’re more economically successful than they are. They want to influence how others view them, as well as reinforce their own sense of confidence or power. The concept of enclothed cognition identifies how color, fabric, and fashion play a part in how we develop our identities.

One study proposed a two-prong effect of symbolic meaning and physical experience. The researchers put subjects into lab coats, a clothing item associated with focus. The subjects participated in tasks that involved attention. Compared to controls, the research group showed increased attention to detail, especially when the coat was described as a doctor’s lab coat versus a painter’s smock. The researchers concluded that, when there’s a specific context of meaning, clothing influences the wearer’s psychological processes.

Clothing communicates. We can play roles more easily in costume. Clothing might even help to present a persona that’s different from our everyday selves. The more we identify with a specific outfit, the more it can impact our self-esteem and behavior. Our outfits help us to rise to the occasion, as the imbued expectations convey goals. Whether you dress for business, medicine, sports, cooking, or art, there’s a uniform of some sort that helps you to feel the part.

For killers, there’s clothing for power, for terror, or for concealment. Fictional boogeymen often wear masks, and so did some real-life killers. In 1946 in Texarkana, the “Moonlight Murderer” targeted couples parked in lovers’ lanes. Five were killed and three injured. One couple that survived told police they’d seen a man in a white mask with holes cut for the eyes and mouth. California’s Zodiac Killer, too, wore a mask during at least one fatal assault. Between 1968 and 1969, he killed at least five people (he claimed more). Never identified, he seems to have approached one couple in a park wearing a black executioner-style hood.

Trench coats have become symbolically loaded for school shooters. Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold wore them during their suicidal assault on Columbine in 1999, but even three years before them, Barry Loukaitis dressed in a black duster like a Wild West gunslinger before he killed his teacher and two students in Moses Lake, Washington.

Dennis Rader, the “BTK” killer in Wichita, Kansas between 1974 and 1991, used several different outfits to support a deadly ruse. In one, Rader wore an Air Force parka to make a military impression. For a different impression, he donned a tweed jacket and carried a briefcase. To approach his ninth victim, he glued a telephone company logo from a phone book to a hardhat to make her think he was there as a repairman. It worked, and a young woman died.

Clothing can enhance one’s sense of identity, and with it the motivation and confidence to play a role. Only a few killers have articulated what their murder clothes mean, but it’s safe to say that, for predators, how they dress is part of their preparation.

References

Adam, H. & Galinsky, A. D. (2012). Enclothed cognition. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 48(4), 918-925.