DISCLAIMER: Most of the “preliminary” data I will discuss in this post has not been submitted to a peer-reviewed journal although data continues to be analyzed with the goal of submitting a paper in early 2018.

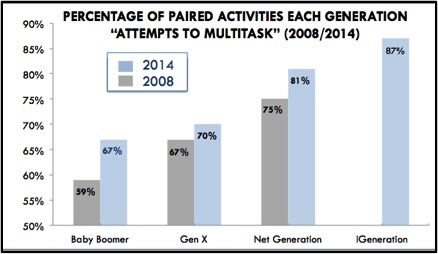

In 2009, my colleague Dr. Mark Carrier and our research lab published an article with data collected in 2008 (Carrier et al., 2009) detailing a cross-generational study—including Baby Boomers (born 1946-1964), Gen Xers (1965-1979) and Net Geners (1980-1989)—that asked participants if they attempted to perform various pairs of tasks together. Presenting all possible pairs formed from 12 tasks (nine technology tasks and three non-tech), sample questions included:

“Do you attempt to play a video game and text someone at the same time?”

“Do you attempt to go online and read a book at the same time?

Six years later we replicated the study but now included the iGeneration (born between 1990 and 1999) who were too young to participate as adults in the initial study. The following chart shows the percentages of pairs that each generation claimed that they “attempted” to do together. Over the six years, each generation claimed to attempt to multitask more pairs and strikingly, the iGeneration claimed that they attempted to multitask 87 percent of the pairs, which included, for example, reading a book and doing other technology-related activities. Each generation showed an increase although the Gen X change was not statistically significant.

In 2013, our lab created and published a measurement instrument called the Media and Technology Usage and Attitudes Scale (MTUAS; Rosen et al., 2013) that assessed the frequency with which one checked various technology devices, apps, and websites and yielded 11 usage subscales as well as three attitudinal subscales. The MTUAS was used in five studies between Fall 2014 and Spring 2017 with groups of similar upper division university students completing the same measure. These students were all taking the same upper division course taught by the same professor. The composition of these student groups did not differ on age (Mean = 25) on any other relevant demographic. Examining the MTUAS subscales the following trends were found over the three and a half-year period:

Increasing Trends:

► Smartphone usage

► Social media usage

► Texting

► Anxiety about missing out on technology (FOMO)

Decreasing Trends:

♦ Use of email

♦ Number of Facebook friends

♦ Media sharing

It is important to note which technology uses increased and which decreased. Not surprisingly, given the omnipresence of smartphones, the frequency with which they are checked daily has increased perhaps as a function of using more social media and texting more often—as I have mentioned in earlier posts and found in models that predict sleep problems (Rosen et al., 2013) and academic course performance (Rosen et al., in press). Equally striking is the use of email has decreased most likely due to additional communication through texting and social media. Also dropping were Facebook friends (more on that below) and media sharing, which includes watching media on a computer. This most likely decreased due to more use of a smartphone and, thus, more media sharing on phones and not on computers.

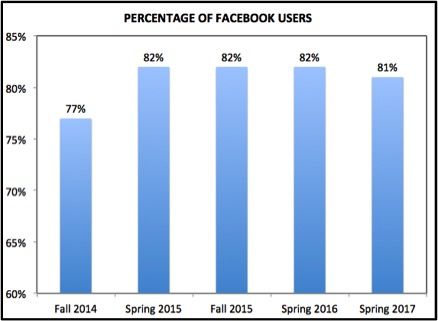

In addition, data were collected for each sample on the number of participants with a Facebook account with the following results showing relatively constant Facebook account holders over the same time period. This means that the rumors that people are leaving Facebook in droves are not true although they do have fewer Facebook friends now compared with three and a half years ago.

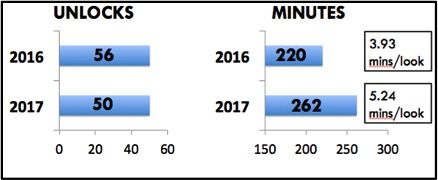

In the last two observation periods, Spring 2016 and Spring 2017 students were asked to use a smartphone app (Instant Quantified Self) that assessed the number of times the phone was unlocked each day and the number of minutes it remained unlocked. The chart below indicates that in 2016 smartphone users unlocked their phones 56 times a day (about every 15 minutes of awake time) for a total of 220 minutes a day (3 hours, 40 minutes) equating to just under four minutes per unlock. A year later, the number of unlocks dropped slightly to 50 but the total minutes increased dramatically to 262 minutes a day (4 hours, 22 minutes) or more than five minutes per unlock. In the final study in 2017, we also asked specifically about social media usage and those data may shed light on why the smartphone users were spending more time on their phone during each unlock period.

Each participant was asked if they had an active account on the 11 different social media sites with the most users. The typical participant indicated having active accounts on nearly six of the 11 sites with the top four including YouTube (84 percent), Instagram (83 percent), Facebook (81 percent) and Snapchat (79 percent). When asked how often they checked those four accounts, the “typical” response ranged from once a day for YouTube, several times a day for Facebook, to once an hour for Instagram and Snapchat. Given the changes we have seen, it is likely that the impetus for remaining on one's smartphone for an additional 1.31 minutes may be due to feeling a need to check in with social media accounts.

What does this all mean for the future?

I am asked this question often and my response is that from a consumer science point of view, most innovations act like an upside-down pendulum, starting slowly, reaching a peak and then abating. Some follow this pattern rather quickly (Google Glass, Pokémon Go) while others stall at the peak and maintain their highly active use with no sign of slowing down. In The Distracted Mind: Ancient Brains in a High-Tech World, Adam Gazzaley and I explored what we termed the major “game changers” in promoting distraction. The first was the World Wide Web, the second social media and the third, smartphones that, as Steve Jobs aptly noted, “changed everything.” The Web gave us email and anytime information; social media expanded our world to one-to-many communication and public self-expression and smartphones made it all portable and omnipresent in a single device that fit nicely into our pocket, purse or the palm of our hand. These game changers, I believe, have not yet even reached the apex of their pendulum swing and I don’t see that happening anytime soon. With apps such as Pokémon Go and Angry Birds reaching 50 million users (the standard used to determine when a product has penetrated society) in a month and social media apps such as Instagram and Snapchat taking only a few months to hit that mark and became part of our world we are likely in for more apps that continue to beckon us to use them. In all likelihood, those apps will involve communication as that appears to be the most used aspect of our smartphones.

What will it take for us to stop being so obsessed with our phones and social media? First and foremost we must want to stop checking in as often and stop sleeping with the phone next to the bed and stop checking the phone when playing with our children, eating dinner, watching television, attending church, at a ballgame, and anywhere and everywhere we see people paying more attention to their phones than to the environment and people that are directly in front of them. In a 2016 Psych Today post entitled “Are We All Becoming Pavlov’s Dogs,” I detailed four helpful strategies for eschewing software and hardware and embracing our “humanware.” We can have it all but it will take work to wean ourselves from this obsessive behavior.

References

Carrier, L.M., Cheever, N.A., Rosen, L.D., Benitez, S., & Chang, J. (2009). Multitasking Across Generations: Multitasking Choices and Difficulty Ratings in Three Generations of Americans, Computers in Human Behavior, 25, 483-489.

Gazzaley, A. & Rosen, L. D. (2016). The Distracted Mind: Ancient Brains Living in a High-Tech World. MIT Press.

Rosen, L. D., Carrier, L. M., Miller, A., Rokkum, J., & Ruiz, A. (2016). Sleeping With Technology: Cognitive, Affective and Technology Usage Predictors of Sleep Problems Among College Students. Sleep Health: Journal of the National Sleep Foundation, 2, 49-56.

Rosen, L. D., Carrier, L. M., Pedroza, J. A., Elias, S., O’Brien, K. M., Lozano, J., Kim, K., Cheever, N. A., Bentley, J., & Ruiz, A. (accepted for publication). The Role of Executive Function and Technological Anxiety (FOMO) in College Course Performance as Mediated by Technology Usage and Multitasking Habits, Psicologia Educativa (The Spanish Journal of Educational Psychology).

Rosen, L.D., Whaling, K., Carrier, L.M., Cheever, N.A., and Rokkum, J. (2013). The Media and Technology Usage and Attitudes Scale: An empirical investigation. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6), 2501-2511.