Leadership

Leaders Adapt to New Realities

To make your vision real you have to deal effectively with reality.

Posted December 18, 2023 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- Leaders size up a new reality and adapt to it

- Team-building is key to helping an organization to adapt

- You cannot be sentimental about leaving behind old, comfortable MOs

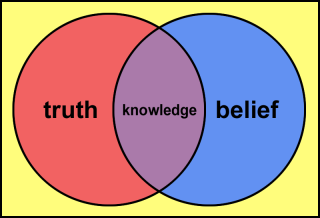

- Teams should intersect like a Venn diagram, with the leader at the center

“Adaptation” might be the title of Burt’s life story. Burt was fortyish, and obsessed with intermodal transportation: freight cars with containers off-loaded onto barges, then locally onto trucks. When he turned up in my office, his vision was to become the country’s largest intermodal shipper of refrigerated produce. While it was not glamorous, it was grounded in the undeniable reality that food needs to get to people who will eat it.

Burt inherited his vision. His grandfather had owned a fleet of trucks, and was known in the city for on-time, reliable deliveries. His father had joined the business, but when he tried to expand into the tri-state area he was clobbered by Mob operators. The business barely survived. Even at its best, it could not meet industry logistical standards. Burt was determined to rescue the firm, to bring it into the 21st century—and then to become a real player.

“Okay,” he told me. “I know it’s a challenge. But I see the possibilities.” Burt had worked in the business since college, mainly in accounts receivable, but now he succeeded his father as president. “It’s up to me,” he said.

Burt’s father had started grooming him to take over and had introduced him around but had never allowed him to get involved enough to credibly run the business—salespeople, dispatchers, drivers, contractors, facilities maintenance, truck maintenance, billing, purchasing—a world of interlocking pieces that had to be coordinated and, as Burt now saw it, massively upgraded. For example, “sales” had to become CRM. Dispatch had to segue into logistics. The challenge was huge. But as we talked, he thought maybe it didn’t matter that nothing was quite right. “I’m going to reinvent the place,” he said.

His idea was that you don’t just “grow a business.” You allow it to grow by tackling problems head-on—with everything you’ve got—so that they don’t get worse. So that they don’t make everything else a problem. So that problems finally disappear and let you tackle the next one.

In college, Burt had been the captain and quarterback of his frat-house football team. He was a motivator. When he saw shoddy playing, he called it out. He would analyze the opposing team’s moves and devise new plays to block them. When he was on the field, he played as if his life depended on winning, and he expected a similar commitment from everyone. “I’m a team-builder,” he said, “and teams solve problems.”

We discussed how all this would play out, so to speak, in building a next-gen, not-your-father’s shipping company. Burt hired a group of software engineers to analyze the potential tri-state market, spot bottlenecks, calculate effective price points for the various submarkets, and produce an algorithm that would allow him to adjust going forward. “I wanted to be on top of the market,” he said, “not just following the big guys. I needed a continuing source of intelligence that my salespeople could use.” Those salespeople were now learning to use CRM, to stay in touch with customers and monitor their daily, seasonal, annual needs on a product-by-product basis.

Burt realized, of course, that however nimble he was, he couldn’t compete on efficiencies of scale with the big refrigerated truckers that could always underbid him. His father never worried about them because he wasn’t after their customers. But Burt was. He hired another team to make the case to small shippers that merger was the only survival strategy.

Nor did he stop with trucking. He contracted with rail lines that handled refrigerated containers. He saw an opening beyond his original tri-state market. “I had to adapt to reality,” he told me. Reality is intermodal.” His father hated containers because they all looked alike. Now Burt knew where every container was, 24/7. “If you’ve got the technology,” he said, “you’ll never lose a single banana.”

When the pandemic hit, Burt saw his biggest opening. Refrigerated carriers were suddenly indispensable. Burt adapted by going into capital markets with gusto. He developed a business plan that would attract investors.

Of course, Burt had to allow a couple of the private equity guys onto his board, but he understood that he was no longer running a family operation. Part of adapting to reality is letting go of old, comfortable models for those that are open to new possibilities. If the private equity guys squelch some of his initiatives, his job—as he saw it —was to help them adapt as well. Burt was essentially fearless. Not impetuous, but convinced that if he put in the work and exercised his imagination, he’d bring other people along with him.

Will Burt ever rival the multi-billion-dollar behemoths? He’s still got time. But his story demonstrates that having a vision means executing a series of detailed plans. Do you give yourself and others the chance to do that? Leaders can’t afford to be impatient. They are also adept at keeping a dozen balls in the air at once and making sure that they all hit the ground in the right order. Some problems depend for their solution on solving other problems. Knowing when you’re ready to tackle the next problem is crucial, and that knowledge comes from understanding the depth of a problem and its ramifications throughout the rest of the operation.

How do you do that? By consultation with your teams and by developing a deep understanding of what they know. If teams think they can get away with doing less, they may be tempted. Don’t let them even think of it. You should talk their language, gain their confidence, even inspire their admiration. You should ask the kind of questions that suggest you could probably provide a pretty good answer on your own.

Finally, it’s crucial to encourage your teams to feel like they’re part of your vision, i.e., that they’re making it happen. They should care about whether you succeed and are entitled to expect proper credit. Remember, you’re not an island—so don’t act like one. Actually, part of your role as a leader is to promote communication among teams. So, determine how their tasks intersect, and facilitate useful in-person connections. Think of your teams as forming a living Venn diagram, where your project is central but all the intersecting parts define the center. Keep the conversation going and pay attention.