Psychology

Why I Am a Rabble Rouser in Psychological Science

Keynote talk given at the First Heterodox Psychology Conference.

Posted September 6, 2018 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

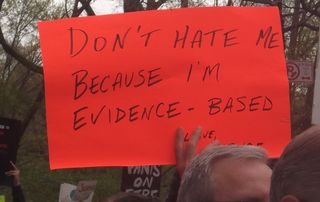

In August 2018, the first Heterodox Psychology Conference for Early Career Scholars convened at Chapman University. Since the meteoric rise of Heterodox Academy, the term “heterodox” has come into fairly common use in academic circles. There is no one definition, but when I use it or hear it used, I think of it as meaning:

- The embrace of diverse viewpoints except when something is so well established that it would be perverse not to believe it. This includes but is not restricted to diverse viewpoints based on demographics (race, ethnicity, class, culture, gender, etc.), politics, and scientific theory.

- The embrace of deep skepticism about many social scientific claims and conclusions pending arrival of evidence so compelling it would be perverse to disbelieve it.

- A rejection of most of the political discrimination and tribalism that pervades much of academia and the wider culture (at least in the U.S., where I live and work). And, no, this does not mean affirmative action for Nazis or communists.

- A degree of open-mindedness, of willingness to consider perspectives that differ from one’s own, and to accord them a certain presumption of respect until something happens to demonstrate they do not deserve it (such as the mass murder and genocide committed on horrendous scales by Nazi and communist regimes).

What follows below is that keynote address, slightly edited to flow better as an essay.

Why I am a rabble rouser

It's an honor to be with you all tonight. It is a unique experience for me to be among so many people to whom I have to explain so little. (I confess to having stolen that line from Alice Dreger’s keynote address at TheFire.org’s first faculty conference).

First, I just want to thank Richard Redding for organizing this; this sort of thing is a tremendous amount of time and effort. It is also exactly one of the (many) things psychology needs to become the scientific discipline it has long claimed to be, and to deserve the esteem and credibility that comes with being an actual science.

But the main reason I want to thank him is that this is the first time I have ever been invited to give a talk, let alone a keynote like this because I am a rabble rouser. Usually, in the past, this meant either avoiding me altogether or, at best, inviting me despite being a rabble rouser. So this will be a bit more of a personal talk than I usually give. In three parts:

- What is a scientific rabble rouser?

- Why am I a rabble rouser?

- Why you might (or might not) want to do it.

What is a scientific rabble rouser?

Rabble rouser? Really? That is the name/theme I chose for myself? What the hell?

In preparing for this talk, I figured I would look up the term. From a quick Google search:

rab-ble rous-er: noun

A person who speaks with the intention of inflaming the emotions of a crowd of people, typically for political reasons.

synonyms: agitator, troublemaker, instigator, firebrand, revolutionary, insurgent, demagogue.

Inflaming the emotions. For political reasons.

At first glance, this looks mostly pejorative. I am definitely not striving to be a demagogue, not even a scientific one. But the more I thought about it, well, yeah. I think moral outrage is actually a reasonable response to many of our field’s dysfunctions.

But moral outrage and its associated anger are energizing. I want you to be energized. I want you, if you want to take it on yourself – and I realize this is not for everyone – to keep others energized about this.

Being a rabble rouser is about energizing people. And about politics. Not political in an ideological Democrats are better than Republicans or conservatives are better than liberals sort of way. But in a grassroots movement sort of way. We need organized efforts, a movement even, to change the normal operating procedures.

Heterodox Academy itself is probably the most visible manifestation of this as a grassroots movement.

It is amazing how successful that has been. It started in Fall 2015, basically when Jon Haidt and Law Prof Nick Rosenkranz shot the breeze. It was founded with about 10 of us. It now has over 2000 members, an active blog series, and an active research arm. It has probably done more to put the problems of lack of intellectual diversity on the map than any academic organization I know.

Another smaller grassroots organization, SIPS (the Society for the Improvement of Psychological Science), sprung up in 2016, and they are probably the vanguard of the effort to improve psychology's methods and practices.

Organizations such as Heterodox Academy and SIPS are necessary because the field is a mess. The psychology elites have mostly failed us, in social psych, that failure has been pervasive.

So mostly, yes, I embrace this definition. Emotions are energizing, and, yes, I hope to energize you into action.

Being a rabble rouser is not for everyone

So let me talk about diversity and science. I think we need super diplomatic scientists who lead by example, never say a harsh word about anything at all, and do not come within a mile of ever criticizing even a paper for concern that it would be taken badly by the authors.

I think we need people who criticize in broad and general terms – say, “the journals need to start publishing replications,” or “look at social psych, it is filled with dramatic studies based on tiny samples!” That is criticism – but it is directed so diffusely, no one can claim “personal attack!”

We need “replicators” – those who do not criticize others’ work but simply try to replicate. When they fail, they simply report it.

And, if (social) psych is ever to become the self-correcting science it claims to be, we need more, not fewer rabble rousers. Agitators; cranky, crabby, thick-skinned people willing to call foul on specific scientific practices, claims, and papers.

Consider other fields. Geologists don’t say mealy-mouthed things about the age of the Earth. You won't hear geologists declaring, "Oh well, some evidence suggests it's 6000 yrs old furthermore others say it's 5 billion years old."

Astronomers used to believe the Sun was made of the same materials as the Earth. They make no bones about saying that was wrong – it was not half wrong, partially right, right under some conditions. It was wrong.

How is anyone to ever know that Paper X actually never provided any data that supported its own claims unless someone says so and shows why that is true?

So, yes, in addition to ideological diversity – we have a whole panel on this, so I am not mentioning this again now – we need, really need, not style points, but stylistic diversity. We need the diplomatic types and we need craggy rabble rousers. We need charismatic types and quiet types who simply but powerfully model better practices.

We actually need all hands on deck.

Why is rabble rousing a way to do this?

Two answers.

- The first is broad and general.

- The second is much more personal, connects back to broad.

My broad and general reasons

My generation of psychological scientists – and I am mostly talking about social psychology here because it is what I know best, though clearly, these problems extend not only beyond social psychology but beyond psychology – especially the most elite, eminent social psychologists, have almost completely screwed it up.

Maybe they did not do it on purpose. Certainly, it is not all of them. Some of the once-lone, but now-gathering voices from my generation that have stood against this are here today. And there are senior and eminent faculty at the forefront of science reform who are not here. It is not all of my generation that caused this.

And I am definitely not saying all of psychology is wrong, irreplicable, or bad. It's not. In fact, the social psychology on attitudes, morality, confirmation bias, partisanship, and conformity is a good part of my basis for being worried about the state of science in our field – but for that to even work implies that I actually give that work considerable credibility – which I do.

Nonetheless, vast stretches of social psychology are a mess. Implicit bias, prejudice, stereotypes, priming, stereotype threat, ego depletion, power posing, the psych of libs/cons, expectancy effects, stereotypes; supposed top-down effects on perception; our workhorse statistics; our methods; meta-analysis; it's all a big fat mess.

My generation is completely responsible for this. We created this. The senior accomplished faculty from my generation almost completely blew it. And many of them still don’t want to hear it and basically won’t listen.

There are some great lines from a hip hop song by Handsome Boy Modeling School called "The Truth":

And the truth hurts because the truth is all there is

You can't hide from the truth, 'cause the truth is all there is

This should be an anthem for any science, certainly psychology.

And if the most eminent won’t lead the way, who will?

- The rest of us

- You. The new generation of scholars, who, as far as I can tell, in general, really want to get it right.

You who, regardless of your our own personal politics, are revolted by the discrimination and even harassment that some people receive in the field because of their political views or contrarian scientific positions; and who are young enough to still be inspired by the vision of a psychological science that, however imperfect we all may be, aspire and work really hard to produce actual truths rather than ideology masquerading as science.

My more personal reasons

I did not start out as a rabble rouser. I attended graduate school in the 1980s. I believed all the stuff I now rail against:

- Self-fulfilling prophecies were powerful sources of social problems.

- Stereotypes were inaccurate and profoundly biased judgments.

- Human social judgment was a menagerie of errors and biases.

I didn’t doubt any of that. I wanted to understand it, build on it, use that understanding to make individuals’ lives better and maybe help ameliorate social problems.

Then I made a terrible mistake. I started doing some actual empirical research. It turned out that:

- It is really hard to get stereotype biases in person perception.

- It is really easy to get people judging others on their merits.

- Self-fulfilling prophecies were weak, fragile, and fleeting.

- Stereotype accuracy is one of the largest and most replicable findings in social psychology.

- The claim that stereotypes are inaccurate itself appears to be inaccurate, exaggerated, not based on evidence, rigidly resistant to disconfirming evidence, and fundamentally illogical.

But then, when I started reporting this work in journals, and in colloquia and conference talks, some funny things happened. I have been told privately, often in a tone that I heard as a patronizing expression of genuine concern for my career, that:

- I'd be much better off focusing on self-fulfilling prophecies than accuracy.

- I did not "want" to be in the business of calling my colleagues hypocrites (this happened twice about 15 years apart).

And I have also been the target of public attempts at humiliation:

- A famous researcher led off her talk at APS with this: "I am glad Lee Jussim lives in a world where all stereotypes are accurate and no one ever relies on them anyway."

- After I reviewed the evidence on stereotype accuracy, the claim was referred to as “nonsense” by a very eminent social psychologist. Publicly. At APS.

These did not happen all at once, they were spread out over years, but there were also other similar things and I am not going to go into each one. And each one could be written off. I mean, we are all the targets of a**holes sometimes. Sh*t happens.

And then I started hearing other people’s stories, often from students, sometimes from other faculty.

I eventually reached the conclusion that it was approximately hopeless to try to persuade most of the Old Guard, my senior colleagues, of pretty much anything. Not that political discrimination was bad; not that their theories were wrong; not that their findings were based on smoke and mirrors. They were (mostly) hopeless.

This was captured beautifully by Nobel Laureate Max Planck:

For most of my career, I felt it was somewhere between difficult and impossible – closer to impossible – to even discuss these sorts of things without being stigmatized as an insignificant and uninformed malcontent. The door to addressing many of social psychology’s dysfunctions was locked and barred tight.

To me, that meant that the door barring discussion of these sorts of issues had to be blasted open.

Even if it meant

- pissing people off

- in the short term, undermining my own influence.

People are not usually persuaded by angry, morally outraged, door-kicking-in types. I get that.

So why? Why kick in doors? Why embrace and advocate blatant rabble rousing?

By making these points – about everything from the accuracy of stereotypes to the wild overselling of implicit bias, from the field’s lack of ideological diversity to its blatant political discrimination, and more – by making these points in the bluntest most direct manner possible, I saw several good long term (not short term) outcomes:

- Some, especially younger scholars and those not heavily invested in the field’s status quo, might be shaken out of their complacency and acquiescence to that status quo.

- Kicking the door open meant that it could become way easier for others to make similar points in perhaps a less grimly blunt style. Once the door is open it is way easier for others to walk in.

- Most important: Science is about truth. Cooperation, playing nice in the sandbox, giving people awards and recognition – it's all-important, part of being human, and it greases the wheels of social interaction. But it is all deeply secondary to science. Our prime directive should not be “be flattering to your colleagues.” Our prime directive should be: Say what is true, to the best of your ability (and part of what is true, as far as I can tell, is that figuring out what is true is much harder than most of us once thought).

Concluding remarks

The risks of being a rabble rouser:

- You will piss some people off.

- You will be written off as "just" a rabble rouser

If these things worry you too much, you risk living in fear – it's not worth it, and I don’t recommend it for you.

Benefits:

- Like anything, you have to do it well. In social psych, that means adhering to norms of evidence and logic. If you do that, no matter how much resistance there is out there, some people will hear you – and it changes some of them.

- You get to say things that, without even trying, without any pretensions of “representing” anyone else, actually speak for other people, by saying things they fear to say themselves. I cannot tell you how many times, over the years, people have contacted me privately, thanking me for saying things they have long thought but were afraid to say publicly.

- You get to put things on the table for debate and discussion – theoretical issues, methods, conclusions, the canon – that have been prematurely accepted as fact. Two things can then happen:

1) The field self-corrects. It ceases being complicit in the purveying of, in essence, fake news and alternative facts.

or:

2) The canon proves right. After a thorough hearing of logic, data, and new data, it can turn out that the received wisdom is true. But now it is on a way firmer logical and evidentiary basis than previously.

Either way, social psychology, or psychology, ends up on a much sounder scientific basis than before rabble rousing started. Personally, that is incredibly satisfying.

And professionally, putting psych on a firmer scientific basis is what all of this, including rabble rousing, is all about.

Epilogue

This is a true story, but one that I will use as a metaphor for what I hope this conference will be. There is a café in San Francisco, called Trouble. It is called Trouble in homage to the people who helped the owner when she was down and out. She was, for a while, homeless. Still, she kept a journal even then, writing furiously.

And the core element of her philosophy was to learn to live with commitment, courage, and honor. And she distilled those ideas down into this one phrase:

Build your own damn house.

And that is part of what I am hoping we do here – build our own damn house. Many of us have, for a long time, felt homeless in our own field. A home is a place of refuge and even safety from a world that is often hostile and out to kill you, if not literally, at least professionally. On the other hand, I am not saying once we build that house, never to come out of it. It is invaluable to have a secure base, but, not one to which we withdraw, but one from which we go forth to engage our colleagues and the wider world.

So, in that spirit, let’s build our own damn house. And make some Trouble. Thank you.