Psychiatry

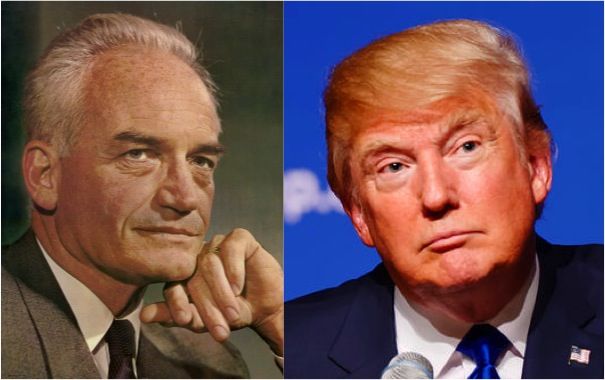

Goldwater 2016: Are Psychiatrists' Opinions of Trump Rigged?

5 reasons why psychiatrists and psychologists should heed the “Goldwater Rule”

Posted October 25, 2016

“The main factors which make me feel Goldwater is unfit to be president are: 1) His impulsive, impetuous behavior. Such behavior in this age could result in world destruction. This behavior reflects an emotionally immature, unstable personality. 2) His inability to dissociate himself from vituperative, sick extremists. Basically, I feel that he has a narcissistic character disorder with not too latent paranoid elements.”5

– Carl B. Young, psychiatrist commenting on Barry Goldwater in 1964

This election year, mental health professionals seem to have been poised, not unlike a child with their hand up in class eagerly waiting to be called upon, to offer a psychiatric opinion of Donald Trump for the mainstream media. And several have risen to the occasion, or taken the bait, depending on one’s perspective.

The cascade started in late 2015 with a Vanity Fair article entitled “Is Donald Trump Actually a Narcissist? Therapists Weigh In!” that quoted liberally from psychologists and “psychotherapists” to form an unflattering “psychological profile” of the candidate. Then, in January of this year, Raw Story published a piece that went viral by fellow Psychology Today blogger Bobby Azarian called, “A Neuroscientist Explains: Trump Has a Mental Disorder That Makes Him a Dangerous World Leader” in which Trump was likened to Gollum from Lord of the Rings. Come June, Northwestern University psychologist Dan McAdams penned an article for The Atlantic called “The Mind of Donald Trump: Narcissism, Disagreeableness, Grandiosity – A Psychologist Investigates How Trump’s Extraordinary Personality Might Shape His Possible Presidency” in which the author drew a psychological “portrait” based on “well-validated concepts in the fields of personality, developmental, and social psychology” that concluded that Trump’s “basic personality traits suggest a presidency that could be highly combustible.” Finally, in July, things came full circle in the Washington Post with another article that quoted from random psychologists to affirmatively answer the question, “Is Trump a Textbook Narcissist?”

By the end of the summer heading into the final months of the 2016 presidential election, it’s therefore likely that readers of the mainstream media had come to believe that qualified mental health professionals had consistently diagnosed Donald Trump as a “narcissist” (see my previous post about the misuse of this term) if not having narcissistic personality disorder. This sequence of events led the American Psychiatry Association’s (APA) president Dr. Maria Oquendo to issue a reminder in August about the “Goldwater Rule,” an ethical proscription against offering professional psychiatric opinions about public figures without proper authorization or consent:

“On occasion psychiatrists are asked for an opinion about an individual who is in the light of public attention or who has disclosed information about himself/herself through public media. In such circumstances, a psychiatrist may share with the public his or her expertise about psychiatric issues in general. However, it is unethical for a psychiatrist to offer a professional opinion unless he or she has conducted an examination and has been granted proper authorization for such a statement.”1

Why the “Goldwater Rule?” In the 1964 election, over 2000 psychiatrists responded to a poll by Fact magazine, with about half of them opining that Republican candidate Barry Goldwater was not “psychologically fit” to be president and some suggesting that he had narcissistic personality disorder or even schizophrenia, calling him a “megalomanic” and an “anal character.” Needless to say, Goldwater went on to lose the election to Lyndon Johnson and successfully sued the magazine for libel (read the more detailed history here and here). Dr. Oquendo’s recent reminder about the Goldwater Rule noted that the psychiatrists’ ethical misstep at the time “violated the spirit of the ethical code that we live by as physicians, and could very well have eroded public confidence in psychiatry” and went on to say of present circumstances that:

“We live in an age where information on a given individual is easier to access and more abundant than ever before, particularly if that person happens to be a public figure. With that in mind, I can understand the desire to get inside the mind of a Presidential candidate. I can also understand how a patient might feel if they saw their doctor offering an uninformed medical opinion on someone they have never examined. A patient who sees that might lose confidence in their doctor, and would likely feel stigmatized by language painting a candidate with a mental disorder (real or perceived) as “unfit” or “unworthy” to assume the Presidency.

Simply put, breaking the Goldwater Rule is irresponsible, potentially stigmatizing, and definitely unethical.”2

The most convincing summary that I’ve ever read of why the Goldwater Rule makes sense for psychiatrists – and psychologists – was outlined in a 2014 Psychiatric Times article by Cornell psychiatry professor Richard Friedman called “Discussions about Public Figures: Clinician, Commentator, or Educator.” In it, Dr. Friedman noted:

“For a mental health professional – or any physician – to publicly offer a diagnosis of a nonpatient at a distance not only invites public distrust of these professionals, but also is intellectually dishonest and is damaging to the profession. After all, a professional opinion should reflect a thorough and rigorous examination of a patient, the clinical history, and all relevant clinical data under the protection of strict confidentiality, none of which is possible by casual observation of a public figure. To do otherwise is unethical because it violates this fundamental principle and thereby misleads the public about what constitutes accepted medical and nonmedical professional practice.”3

Despite the clarity of the APA’s admonition and the soundness of Dr. Friedman’s statement, several arguments have emerged suggesting legitimate exceptions to the Goldwater Rule, without consensus. After a recent “online manifesto against ‘Trumpism’ signed by more than 2,200 mental health specialists” was recently published online, New York Times writer Benedict Carey asked, “The Psychiatric Question: Is It Fair to Analyze Donald Trump From Afar?” and noted that “if there are exceptions to the Goldwater Rule, psychiatrists apparently cannot agree on them.”

Indeed, a central principle of the Goldwater Rule is that psychiatrists should not engage in “arm chair” diagnosis without a face-to-face exam. Columbia University psychiatrist Robert Kliztman iterated this principle in a New York Times op-ed piece earlier this year:

“To diagnose conditions in someone we’ve never met – let alone offer treatment recommendations – is fraught both ethically and scientifically. Assessing patients face to face and finding out their experiences and history, much of which is private, and has perhaps never been disclosed to anyone, is essential. Otherwise, we risk making big errors and fostering confusion.”4

But Tufts University psychiatrist Nassir Ghaemi has argued that psychiatric diagnosis can be performed without a “personal examination” if there is “sufficient documentation – from whatever source, whether it be the patient or not – to support the diagnosis.”6 Just this month in a Slate magazine article entitled, “It’s OK to Speculate About Trump’s Mental Health,” psychiatrist Sally Satel agreed that because of changes in how psychiatrists diagnose based on check-list criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), “it is now possible to make a psychological assessment from afar.”

Others have argued that the arm chair diagnosis of public figures can be justified if the individual in question presents a danger to the public. Dr. Jerrold Post, founder of the Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) Center for the Analysis of Personality and Political Behavior, was chastised by the APA after testifying before Congress in 2000, providing a psychiatric analysis of Saddam Hussein. In a subsequent article, Dr. Post responded that he had provided a “political psychology profile” rather than a “psychiatric expert opinion” and that in any case, the “duty to warn” the public about a dangerous individual superseded the ethical concerns of the Goldwater Rule.5

Dr. Ghaemi made a similar argument, noting that psychiatric diagnosis in the absence of a face-to-face exam may be warranted if adequate evidence is available to make a diagnosis and “only if [the psychiatrist] deem[s] the political and social circumstances serious enough that their duties as citizens in a democracy outweigh their responsibilities as regulated professionals.”6 In an academic paper published this year, psychiatrists Jerome Kroll and Claire Pouncey went so far as the claim that the Goldwater Rule is itself unethical, because it “suppresses public discussion of potentially dangerous public figures.”7 In this spirit, although he condemned the practice of “slander by diagnosis,” Dr. Post suggested that the Goldwater Rule should be abandoned altogether.5

Finally, Psychology Today blogger Dr. John Mayer reminds us that psychologists aren’t technically bound by the Goldwater Rule, perhaps because the profession doesn’t always involve a clinical responsibility as psychiatry typically does.

With so many different opinions about the Goldwater Rule, it’s little wonder that we’ve seen so many public commentaries by psychiatrists, psychologists, neuroscientists, and psychotherapists this election cycle. Following the publication of my last blogpost, “Scoring the Presidential Debates: How Do We Decide Who Wins?,” I myself participated in a television interview about the first debates between Trump and Hillary Clinton (you can view it here). As things got started, the newscaster soon asked me “from what you could tell, looking at them on the stage… what could you read into [the candidates’] own mental state?” Taking a page out of the debate itself, I dodged the question, staying true to the Goldwater Rule.

In my view, the Goldwater Rule is a sound ethical guideline and I always find myself wondering how some psychiatrists and psychologists convince themselves that it's okay to violate it. No doubt the lure of being featured in the media as an expert can be strong, but I’m not convinced by the arguments that the Goldwater Rule has justifiable exceptions. Here are 5 reasons why:

1. The Goldwater Rule should apply to psychiatrists and psychologists alike. Should psychologists really be exempt from the Goldwater Rule? Following Dr. Klitzman’s New York Times op-ed piece earlier this year, the American Psychological Association (the other APA) gave us an answer to this one, with its president Dr. Susan McDaniel cautioning:

“The American Psychological Association wholeheartedly agrees [with Dr. Klitzman’s NY Times op-ed]… that neither psychiatrists nor psychologists should offer diagnoses of candidates or any other living public figure they have never examined… Similar to the psychiatrists' Goldwater Rule,’ our code of ethics exhorts psychologists to ‘take precautions’ that any statements they make to the media ‘are based on their professional knowledge, training or experience in accord with appropriate psychological literature and practice’ and ‘do not indicate that a professional relationship has been established’ with people in the public eye, including political candidates. When providing opinions of psychological characteristics, psychologists must conduct an examination ‘adequate to support statements or conclusions.’ In other words, our ethical code states that psychologists should not offer a diagnosis in the media of a living public figure they have not examined.”8

2. An interactive, face-to-face examination is the gold standard for psychiatric assessment, unless such an exam is not possible. While it’s technically true that psychiatric evaluations can be made by running through DSM symptom checklists in a cookbook fashion without a face-to-face exam, that kind of diagnostic assessment falls short of what would be expected by a psychiatrist in a clinical setting. For example, if one of the current presidential candidates called me for help with pre-election jitters and insomnia, I wouldn’t just write them a prescription based on what I’ve seen on television or read on the internet thus far. I’d schedule an appointment with them and after a thorough assessment, or perhaps several, I’d recommend a course of action. Based on a clinical standard, arm chair diagnosis without interviewing an individual in an interactive fashion isn’t an examination at all, it's malpractice. If that isn’t adequate for clinical work, it shouldn’t be sufficient for offering a diagnostic opinion in a public commentary.

3. Media portrayals of public figures are unreliable and potentially biased. Although Jerry Seinfield was no doubt something like his character on his eponymous show, I wouldn’t make the mistake of assuming that they were the same person. Just so, attempting to evaluate a presidential candidate based on a debate or a stump speech risks mistaking the individual for their public persona. While we get a glimpse of a public figure through their onscreen presence, that visible window is incomplete. To complicate matters further, what we do see of the candidates has often been compressed into a sound bite, sometimes with the larger context of what was said edited away. Video editing can profoundly alter how a candidate is portrayed (just as different versions of the video of Harambe the gorilla led people to draw different conclusions back in May). Finally, there’s the fact that what we see of the candidates and commentaries about them online is processed through “filter bubbles” and “echo chambers” (see my previous blogpost “Does the Internet Promote Delusional Thinking” for details). In the end, a public figure’s image as portrayed in the media is but a limited snapshot, with significant potential for bias. That does not constitute, as Dr. Ghaemi puts it, “sufficient evidence” for a psychiatric assessment.6

4. Presidential elections do not meet the threshold of “duty to warn.” As for the argument that the duty to protect the public from a dangerous individual ought to supersede the ethical basis of the Goldwater Rule, I agree that this can represent a reasonable exception in some cases. For example, Dr. Post was justified to bypass the Goldwater Rule when he testified in a closed Congressional hearing about Saddam Hussein, just as it would be for a psychiatrist working with law enforcement officials to provide a psychological profile of a mass murderer. But those examples are a far cry from commenting publicly on television or in an online article about a candidate in a presidential election. “Duty to warn” and “duty to protect” exceptions to confidentiality involve disclosing information to police or a potential victim of violence, not to the general public. Say what you will about the candidates, but we’re not talking about individuals who are on the verge of murder.

5. Psychiatrist’s opinions of candidates running for public office are unreliable and likely to be biased. When a psychiatrist evaluates a patient for clinical or forensic purposes, objectivity is a chief goal and the assessment should ideally begin as a blank slate with minimal preconceptions and intentions. But in a presidential election, all of us have preexisting values, party affiliations, and our own stances on hot-button issues that probably determine how we vote more than the candidates themselves. Without some semblance of objectivity, psychiatric opinions about Trump’s mental state should be viewed with the same skepticism as claims that “his strength and physical stamina are extraordinary” or that Clinton has Parkinson’s disease. Just so, judgments about whether or not a candidate presents a risk to public safety would likely fall across party lines rather than reflecting an objective psychiatric assessment.

With that bias in mind, a psychiatrist offering a public comment about a candidate should at least be expected to disclose their political biases, just as a physician is expected to disclose potential conflicts of interest when giving a lecture. While it isn’t known how many of the psychiatrists who claimed that Goldwater was unfit for president were Democrats and Johnson supporters before offering their opinions, a Psychiatric Times reader poll from July 2016 revealed that 66% of respondents (only 43% of respondents were psychiatrists or psychologists) planned to vote for Clinton in this election, with only 22% planning to vote for Trump. That suggests that any psychiatrist’s or psychologist’s opinion about Trump might very well be, dare I say it, “rigged” against him.

Although the title of Dr. Satel’s article suggested that “it’s actually fine” to violate the Goldwater Rule, she acknowledged the potential for bias and cautioned that “the DSM cannot become a political instrument.” In order to avoid political preferences masquerading as expert opinion, it’s best that psychiatrists and psychologists stick to the Goldwater Rule.

Of course, if psychiatrists can’t make reliable assessments of candidates due to insufficient evidence from biased media sources (reason #3) and if their public opinions when they do so anyway are subject to their own political biases (reason #5), we’re left with the question of where that leaves the voting public. How are we as voters expected to make informed, rational, objective decisions about who to vote for come November 8?

Perhaps the only way to answer that is with another question: Do we really vote based on informed, rational, objective analyses of candidates? Or do we just do the best we can with the biased information that we digest together with our own internal biases, ultimately resorting, as Ted Cruz said, to “voting our conscience?”

Dr. Joe Pierre and Psych Unseen can be followed on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/psychunseen/ and on Twitter at https://twitter.com/psychunseen. To check out some of my fiction, click here to read the short story "Thermidor," published in Westwind earlier this year.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. The Principles of Medical Ethics With Annotations Especially Applicable to Psychiatry, 2013 Edition. Arlington VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Practice/Ethics/principles-medical-ethics.pdf

2. Oquendo MA. The Goldwater Rule: Why Breaking it is Unethical and Irresponsible. APA Blog, August 3, 2016.

https://www.psychiatry.org/news-room/apa-blogs/apa-blog/2016/08/the-goldwater-rule

3. Friedman RA. Discussions about Public Figures: Clinician, Commentator, or Educator. Psychiatric Times, March 11, 2014. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/special-reports/discussions-about-public-figures-clinician-commentator-or-educator/page/0/3

4. Klitzman R. Should Therapists Analyze Presidential Candidates? New York Times, March 7, 2016.

5. Post J. Ethical considerations in psychiatric profiling of political figures. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 2002; 25:635-646.

6. Ghaemi N. Is psychoanlyzing our politicians fair game? Medscape Psychiatry, August 15, 2016. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/867320_2

7. Kroll J, Pouncey C. The ethics of the APA’s Goldwater Rule. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law 2016; 44:226-235.

8. McDaniel SH. Response to article on whether therapists should analyze presidential candidates. American Psychological Association, Press Release, March 14, 2016.

http://www.apa.org/news/press/response/presidential-candidates.aspx