Health

From Insane Asylums to Whole-Health, Person-Centered Care

A bit of historical perspective reminds us how far we've come.

Posted April 7, 2019

On March 23, 2010, Barack Obama signed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, commonly referred to as "The Affordable Care Act," or ACA. In 2009, in anticipation of it, Katherine Power, then director of the federal Center for Mental Health Services, published an article in Psychiatric Services titled "A Public Health Model of Mental Health for the 21st Century," in which she described public health as "a population-based approach that supports the development of whole-health, person-centered health care."

It strikes me that while "whole-health" approaches to care are still, to many, novel and innovative, the notion of "person-centered practice" has become, for the most part, the standard of care. Yet just a bit of historical perspective reminds us of how far we have come and how important our increasingly person-centered values are and continue to be as we work together to shape the future of health care delivery for generations to come.

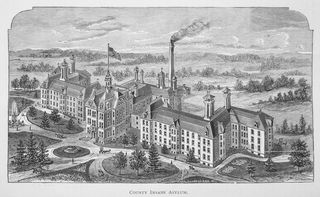

Insane Asylums

By the mid-1800's, mental health treatment was found primarily in large institutions called "insane asylums," also known as "lunatic asylums." In 1842, the Georgia Lunatic Asylum became the largest asylum in the world, boasting by World War II over 200 buildings on 2,000 acres with up to 13,000 patients, under by then the new name, Central State Hospital but widely known by the name of its nearby town, Milledgeville. In 2015, Doug Monroe wrote of Milledgeville,

"By the 1950's, the staff-to-patient ratio was a miserable one to 100. Doctors wielded the psychiatric tools of the times—lobotomies, insulin shock, and early electroshock therapy—along with far less sophisticated techniques: Children were confined to metal cages; adults were forced to take steam baths and cold showers, confined in straitjackets, and treated with douches or 'nauseants.'"

Asylums often did not provide effective—never mind person-centered—treatment for mental health maladies. They were experimental laboratories and, in many cases, elaborate money making schemes. Exhausted parents sometimes enrolled their children in such institutions. Spouses were sometimes committed as a way to escape marriage. Witch hunts of many kinds have been said to have occurred. Many of us take for granted modern behavioral health services and are unaware of the horrors that came before.

Between the mid-1960's and the mid-1970's, a couple of governors of Georgia—Carl Sanders and then later Jimmy Carter—worked to deinstitutionalize Central State Hospital, overseeing the distribution of remaining patients to—I'll say more modern—hospitals, clinics, and other smaller treatment facilities, aided significantly by the advent of a new age in psychiatric pharmaceuticals.

Let's rewind and consider the shape-shifting of the mental health field during that stretch. By the late 1800's, we were still broadly categorizing the mentally ill as "psychotics" and "neurotics." A person now considered to have a "severe and persistent mental illness" was then referred to as "psychotic" and considered "insane" or "mad." "Psychosis" refers to a conditions that affects one's grasp on reality. "Neurosis," on the other hand, is considered to be a mental illness resulting in a comparatively less severe disturbance, such as depression, anxiety, or the like. Neuroses were thought to involve nervous system functioning and had been studied since the 1700's, yet no mainstream treatment for neuroses was available until the turn of the 19th century.

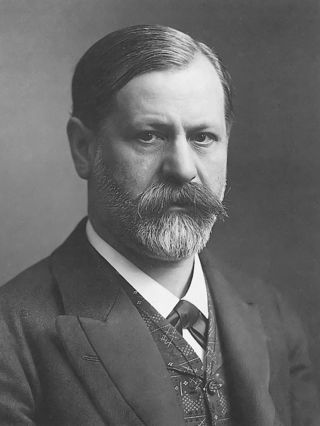

The First Force in Modern Mental Health Care

During the 1890's, young postgraduate Sigmund Freud wrestled to carve his place outside of the academy. In 1900, he published The Interpretation of Dreams, followed shortly thereafter in 1901 by The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, in which he originated a theory of the unconscious. Freud's treatment approach, psychoanalysis a.k.a. "the talking cure," resulted in psychoanalytic clinics popping up around Austria, Europe, the United States, and throughout the Western world.

While the asylum offered the only treatment available to "psychotics," "neurotics" had nearly no treatment option. Freud's psychoanalytic movement resulted in a new option for so-called neurotics. Thousands of psychiatrists left the asylums to pursue a new, exciting, and alternative career option: what we now call psychotherapy. Many did not. It would take more than a half-century more, as I alluded to above, for biological psychiatry to exit the Dark Ages.

Freud's theory was largely deterministic and reductionistic in nature: "deterministic" in that he believed that our futures, and meaningful changes in their course, are largely outside the bounds of our control, and "reductionistic" in that he attributed seemingly complex cognitive, emotional, and behavioral processes to a few universal urges, especially sexual.

Freud's influence in the field constituted what has become known as "the first force" in the field of modern psychology. There is plenty of earned criticism heaped onto Freud. In historical context, Freud's outpatient mental health treatment was in many respects, however, quite impressive, and the reality is that the field of psychotherapy owes a great deal to his innovation.

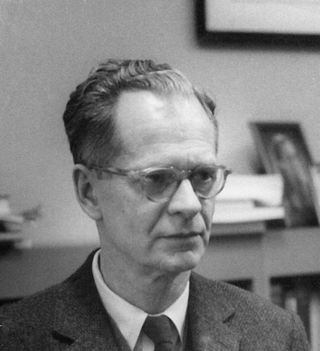

The Second Force in Modern Mental Health Care

The next methodological innovation to capture the imagination of the field was B.F. Skinner, whose behaviorist viewpoint constituted a "second force" in the field. Skinner studied psychology at Harvard and worked to develop objective ways to study behavior. He dismissed the sort of interpretation and conjecture that psychoanalysts employed, believing science would forge the field of psychology into a new and more credible era. Skinner strove to be more scientific, to study only the observable, which meant a clear shift from the study of the mind to behavior.

Skinner's theory was, like Freud's, largely deterministic and reductionistic in nature: "deterministic in that he believed future behavior inevitably results from past learning, and "reductionistic" in that he attributed complex processes to simple formulas involving a stimulus and a response.

Skinner's behaviorism was impressive yet earned its own share of criticism and, ultimately, did not prove to affect a greater impact on health care than the psychoanalysts. While these two overlaying forces worked hard to capture the imagination, the narratives, and the funds of the field for the first half of the twentieth century, a third force—humble, yet bold; diplomatic, yet revolutionary—turned the tide of history.

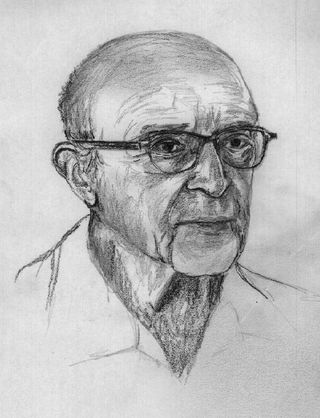

The Third Force in Modern Mental Health Care

Young Carl Rogers found himself new to the field in the 1920's as a psychotherapist working with children in New York. At that time, generally, such clinics gave advice to parents upon interpreting the dynamics in the family affecting the child. Rogers found these practices ineffective and wished to eliminate interpretation and advice and offer an approach that honored the autonomy and individuality of each child and family, rooted in warmth, acceptance, and empathy.

Rogers' approach was unstructured like psychoanalysis but also non-directive, driven by empathy rather than by methodology, with the therapist as facilitator rather than expert, and the efficacy of the therapeutic relationship the crux of research rather than that of interpretation, advice, or targeted behavior modification through external conditioning.

Later at the University of Chicago, Rogers actively shaped new standards of psychotherapy practice, supervision, and research–many which have stood the test of time. Rogers and his contemporaries provided a vision for a reformation, challenged conventions, engaged in qualitative research never before tried in the field, established much needed new ethical guidelines and inspired multiple generations who are now leading the front.

Care Transformation in the 21st Century

We can be proud, by this time, to say that our mental health care system is increasingly person-centered. Now, health care transformation efforts are innovating new value-based models that incentivize smarter use of health care dollars and reward positive outcomes on key indicators, providing opportunities for shared savings and shared risk.

The spread of innovative practices, such as increased use of health information exchanges such as EDIE and Premanage that provide access to patient data across communities' continuum of care, new paradigms for collaborative care including models for medication management consults between physicians and psychiatric prescribers as a standard of care and providing immediate access to behavioral health providers within medical settings, and community-based care coordination models that provide social services case management along pathways of the social determinants of health are just a few examples of systemic transformations aimed at placing patients in the center of their local and regional health care communities rather than forcing them to accommodate to largely fragmented and difficult-to-navigate systems where no one is in the center of anything.

As we reshape the health care system into one that even better values whole health and person-centered care, it is clear to me that we are standing on the shoulders of giants like Carl Rogers. We can look back over the 20th century and see that an obvious and radical transformation took place in the field of mental health. What changes will the 21st century bring?

This article originally appeared at LinkedIn.com.

References

Monroe, D. (2015, February). Asylum: Inside Central State Hospital, once the world's largest mental institution. Atlanta Magazine.

Power, K. (2009). A public health model of mental health for the 21st century. Psychiatric Services (60)5, 580-584.

Rogers, C.R. (1957, April). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21(2), pp. 95-103.