Cognition

Handwriting Reconsidered

Can a step backwards carry us forward?

Posted April 7, 2024 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- Handwriting demands concerted mental and physical effort and so boosts development.

- Handwriting is waning as a skill.

- States are enacting legislation requiring cursive instruction.

Now and then, my inbox overflows when one of these Play in Mind posts strikes a nerve. Some correspondents chime in. Some contest the ideas. And some take me way beyond.

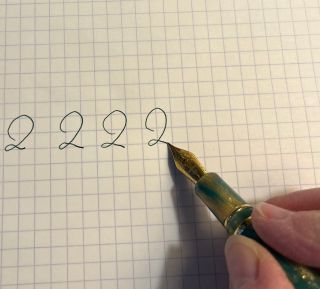

Such is the case with a recent meditation, Handwringing Over Handwriting, which noted how the care required to master cursive was once regarded as a moral exercise essential to building “character.” Contemporary advocates modernize the celebration, citing the promising neurological and cognitive dividends of writing by hand.

The responses that arrived (all by email, of course) tapped into a rich vein of personal recollection and current reflection. The diverse correspondents included university professors and high school teachers, communications coaches, artists, one novelist, and physicians and clinicians whose colleagues’ notoriously crabbed script obliged them to become amateur cryptanalysts.

As artistic sensibility battled with practicality, these observers did not divide neatly into “for” and “against” camps. Some lamented the waning of an art form, meanwhile noting the obvious advantages in the rise of “keyboarding.” For others, the expedient new communications technologies dampened a nostalgic tug for the endangered charm of thoughts rendered visible and personal by a trained hand.

Forgetting Cursive

I did not know that those who cannot write cursive were also unable to read cursive. And I am not the only one. Drew Gilpin Foust, a historian, and former president of Harvard, has recounted how her students regarded her as a version of Rip Van Winkle after she naively asked them if any could not read cursive. (About two in three couldn’t, it turned out.)

In the case of reading the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States, this is not so serious a handicap (outside the cost in authority and authenticity). Those have been transcribed into print. But what of letters from Civil War soldiers, or ancient family correspondence, or property deeds and wills? Or what, for that matter, one wonders, of twenty-first-birthday cards?

Cursive in the Classroom

Thomas Banchich, a professor of classics, wrote that he made this same discovery about ten years ago. He found that students could not read cursive, nor could they read “printed letters that were just a bit off standard fonts on machines.” When script looks only like decoration, deeper trouble followed. “Obviously,” Professor Banchich wrote, “looking at ancient manuscripts or even inscriptions was [for them] spectacularly difficult.” Furthermore, they could print “only with significant difficulty,” he adds, and so were unable to write essays in longhand. Also, that meant that they could not read text written on a blackboard or whiteboard, the standard way that lecturers have long emphasized important points.

Here’s an example. Once upon a time when a class asked me what made the Dark Ages dark, I told the story of the tenth century Holy Roman emperors Otto I, Otto II, and Otto III. Like nearly all other Europeans in that murderous era, the Ottos were illiterate.

I described how they could, nonetheless, sign a royal decree. First, they drew a circle. Then followed it with two tall parallel lines. Then added another circle. Then, demonstrating with chalk, I showed how they would draw a line across the top. Ha! Otto!

Would that joke fall flat now? Would the point be lost?

The Joy of Script

Carolyn Korsmeyer, a novelist, wrote to say how, some years ago, she and her brother had enrolled in a “pen of the month” club. (Yes, that’s a thing.) With the arrival of each new fountain pen they would savor a refreshed, deliberate correspondence. “We wrote regularly to each other,” she said, “a revival of an experience that was so common years ago.” And this brought back how eagerly she had looked forward to receiving letters in college. (The mail came twice a day, then.) Ironically, when the subscription ran out, and despite the convenience of email, “oddly,” she wrote, brother and sister now find less occasion to correspond.

In 1870, M.M. Thompson observed in his instructional handbook that penmanship “embodies thought in a visible language. Under its magic power, ideas assume tangible form, and the eye may trace the operations of the mind.” Modern e-correspondence, more familiar but less personal, thins connection.

Personal but Illegible

Some others who wrote took care to reassure me that my own orthography was not nearly the worst that they had ever seen. One of them, Candice Jones, a retired clinical radiologist from the U.K., said that her practice always required “good clinical information… to sharpen up the quality of my reports.” Throughout her career, she joked, “my subspecialty was deciphering referring doctors’ handwriting.”

Another physician, Jack Freer, and a southpaw to boot, also admitted to “notoriously dismal” handwriting. Lefties smear writing paper. A sixth-grade teacher hatched a bright idea for young Jack. She advised him to “tilt letters \\\\\\\\\\\ instead of /////////.” Alas, “the effect on my brain was a random mix of slants: //\|\\///|||\\\//.”

He attached a cartoon that underlined the personal and professional trouble. A group of angry men in white physicians’ coats, apparently on strike, carry large hand-printed signs. On the signs? Nothing but scribbles.

Onward and Backward

Peter Gray, the evolutionary developmental psychologist, play advocate, and prolific writer, wrote to say that he found no difficulty believing that such a concerted task as handwriting, which “combines messaging with a precise art form” should be linked to mental development.

However, he succinctly framed the practicalities this way. “If I had to go back to the typewriter, let alone longhand, I would say goodbye to book-writing and to 95% of my current enjoyable correspondence.”

At this moment though, approximately half the United States passed or are considering legislation that requires schools to teach cursive. Having had many occasions to pore over beautiful handwritten old documents and letters that waft authenticity and personality, I must sympathize. Still. A historian must be alert to how history unfolds. Our new, efficient processes that began with manual typewriters will ensure that productivity will triumph over art. Likely, as my cyber-savvy colleague Lenore Sarasan wrote, artificial intelligence will soon read script for us. Even mine.

Like boats against the current, those who mean to rescue us from the surging future are borne back, nostalgically, into the past.

References

David A. Gerber, Authors of Their Lives: The Personal Correspondence of British Immigrants to North America in the Nineteenth Century (2005); Tamara Platkins Thornton, Handwriting in America: A Cultural History; M.M Thompson, A Hand-Book to Accompany the Eclectic System of Penmanship (1870); S.A. Potter, Penmanship Explained: The Principles of Writing Reduced to an Exact Science (1868).

Drew Gilpin Faust, “Gen Z Never Learned to Read Cursive: How will They Interpret the Past,” The Atlantic, (October 2022); Mark Oppenheimer, “The Lost Virtue of Cursive,” The New Yorker (October 22, 2016), Mary McNaughton Cassill, “Should we Celebrate or Mourn the End of Handwriting,” Psychology Today (March 6, 2023).