Memory

Playing to Learn with Memory Games

The lesson of the left-hand thread.

Posted January 22, 2024 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- Play comes to the rescue for complex memorizing.

- Rule-making is part of play.

- Part of rule-making is rule-breaking.

I once worked at a propane distributorship where I learned two things that stuck—how to back up a trailer holding a 1,000-gallon tank so that its four steel feet would settle squarely on small blocks. And then something quite different: how to defy a basic object lesson, “righty tighty, lefty loosey.”

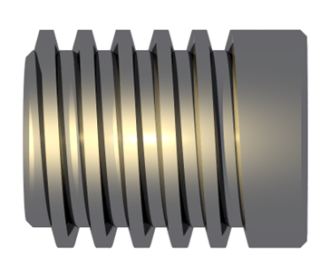

Learning to screw in a screw, clockwise, is a technique so elementary that it is hard to unlearn. And why would one want to? Clockwise is a concept so thoroughly embedded in us that our forebears knew of clockwise motion even before clocks appeared. Sundials that follow a clockwise arc likely inspired clockmakers to make the hands move left to right. All these years later, jar lids and the caps on anchovy paste tubes still follow this rule.

In fact, human anatomy and the remarkable human hand favor this right-handed motion. In a right-handed person, and that’s most of us—sorry, southpaws— the action called “supination,” a twisting to the right, is stronger and more easily coordinated than “pronation,” the counterclockwise movement that loosens a screw.

But I learned that the fittings that connected a flammable gas to its uses featured left-hand threads. The official reason, so I was told, was to keep the uninitiated from fooling with piping. Fuel gas bottles are still distinguished from non-fuel tanks by left-handed threads—save for one instance. Connecting the tank to the gas grill now tightens as it rightfully should, to the right.

More than once, way back when, bewildered and flummoxed customers brought me empty cylinders to fill with the supply lines still attached, having dismantled the barbecue grill. I always sympathized. Sometimes, even I would catch myself, saying “nope!” out loud when tempted to tighten a fitting the “right” (wrong) way with the overriding mnemonic ringing in my ears.

If you have ever had the occasion to navigate a roundabout in Britain or Ireland, where your right hand is nearest the center line, you may have resisted a similar force of habit with a more consequential mnemonic, “put your right shoulder to the center.” At home we drive on the right with steering wheels on the left, so our traffic circles go counterclockwise. It’s devilishly the opposite across the pond; thrilling in its way, but confusing. A waggish Irish friend once coached me about how to remember to exit left from a clockwise traffic circle in County Kerry by invoking the initiation rite in The Karate Kid. “Just remember,” she said wisely, circling first her right then her left hand, “wax on, wax off.”

Memory Aids Burrow Deeply

The alphabet song, the most familiar of all mnemonics, is similarly irresistible. It is hard enough to recite the alphabet backwards: z, y, x, w, ummm, er, v… But it is next to impossible to sing the song backwards. Choral composers can reverse the flow because the music lives in them. But the rest of us cannot, because for us casual singers, a song always flows forward. It is the direction of the notes that we remember.

To keep our thoughts straight we have recourse to a variety of memory aids, notepads, PowerPoint slide shows, cue cards, and TelePrompTers. But to sharpen their prodigious recall, preliterate speakers—bards, troubadours, praise-singers, and griots of the misty past—relied on a variety of wordplay games, along with rhymes and rhythms and alliterations.

Building a Mental Memory Palace

The tricks weren’t just for those poets and singers who could not read or write. Greek and Roman orators slated to deliver long speeches without notes devised their own playful and serious rule-bound strategies. They would construct an elaborate mental “memory palace” to keep their message from wandering. They labeled every imagined architectural detail, every envisioned step and balustrade, every column and window frame with visualized signage, keywords of their orations’ directions.

Play Comes to the Rescue

We still rely on wordplay for learning and recall. When asked to list the Great Lakes, fourth-grade geography students resort to an acronym, HOMES. Novice pianists obliged to remember the notes of the G clef think of an exhortation “every good boy does fine!” And as for remembering the sequence of the visible spectrum, a fellow named Roy G. Biv will do.

Sorely beset medical students need to master a vast new and minutely technical vocabulary. Of the many clever mnemonics that they turn to, here is just one, for memorizing the complicated anatomy of the wrist: “She Likes To Play, Try to Catch Her.” Which refers to, bear with me a moment, scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, pisiform, trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate. See why this game comes in handy?

Likewise, committing legal jargon to useful memory sorely challenges those prepping for their law boards. And so, while cramming they recruit ditties, rhymes, acronyms, and jokes. When in a courtroom proceeding defense attorneys ask a judge to exclude relevant evidence, they may ask her to order the SOUP.—arguing that an inadmissible fact is Substantially Outweighed by its Unfair and Prejudicial impact on a jury. (If the defendant is charged with following too closely, it wouldn’t be relevant to reveal that he cheats on his golf scorecard.)

Specialized lingo often challenges learners. But we’re not helpless: Play comes to the rescue. Once, for a geology class, I took advantage of this one to remember the sequence of bygone eras whose names seemed as hazy as dilithium crystals: Precambrian, Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic. I still remember the memory game that helped, “Pizza Places Make Chicken!”

A final thought. Players seek rules to make play fairer and more predictable. But play also holds the seeds of creativity and innovation. Part and parcel of rule-making, somewhat paradoxically, is rule-breaking. And this mischief applies as much to poets who break meter and rhyme as it does to machinists who devise a left-handed thread.

References

Scott G. Eberle, “Playing with the Multiple Intelligences: How Play Helps Them Grow,” American Journal of Play, volume 4, number 1, (Summer, 2011).

Frank R. Wilson, The Hand: How its Use Shapes the Brain, Language, and Human Culture, (1999).

Francis A. Yates, The Art of Memory (1966); Nigel J. T. Thomas, “Ancient Imagery Mnemonics,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2017 Edition). (Retrieved 19, January 2023).