Halloween gives children the opportunity to celebrate and tame fearful figments of the imagination. Celebrants who play at spooky, scary, fantastical, or satirical portrayals strengthen their sense of the normal and their confidence in the permissible.

We Americans gleefully now spend more than $3 billion each year on readymade Halloween costumes and decorations. Last weekend, for example, I saw scores of little costumed denizens as they made their way to the annual party at the Buffalo zoo. The parade featured “top scarers” from Monsters Inc., Minions from the Despicable Me series, and a variety of Minnie Mouses; I recognized Ninja Turtles; Elsa and Olaf from Disney’s Frozen; Captain America, a surplus of Batmen, Supermen, and Spidermen; generic witches; assorted fairies; two smiling dinosaurs; the crocodile from Captain Hook; a stuffed pumpkin; a simple ghost or two; and naturally for this venue, lots of animals, including little elephants, a cow, and even a stylized skunk. One proud mother had outfitted her triplets as a lion, tiger, and bear. (A voice behind me yelled out, “Hey look! Three twins!”)

All these characters and one striking omission: The parade prominently featured goblins and superheroes, and the usual princesses, but there appeared not a single, solitary clown. A Halloween parade without clowns? Curious.

Clown costumes once flourished. Propelled by film and television, clowns became a mainstay of the 20th-century American Halloween. Charlie Chaplin’s loveable Tramp was a kind of clown; in the 1920s, trick-or-treaters imitated his bowlegged walk. A decade later, kids channeled Emmet Kelly—another sympathetic, melancholy hobo. In the 1950s, television gave us the sweet, silent Clarabelle the Clown. He would delight the peanut gallery at the Howdy Doody Show by squirting “Buffalo” Bob with seltzer. Bob would then lead the sing-along to the tune of “Mademoiselle from Armentières” for “Who's the funniest clown we know?/Clar-a-belle!” After 1960, Bozo the Clown, another TV star, inspired Halloween costumes. His comic, teased-out, big orange hair scared nobody. In fact, clowning can be healing. Patch Adams and Bowen White, both physicians, travel the world as clowns ministering to sick bodies and broken souls.

This year, though, TV news enthusiastically reported uncorroborated sinister “sightings” after children in South Carolina described a clown (or perhaps groups of “whispering” clowns) that they believed inhabited a local wood. Though police found no evidence, the contagious meme spread on social media. A few teenage pranksters and grown-up performing artists fed the craze. Reports of menacing clowns soon spread to nearly all fifty states.

These clown-hoaxes rarely caused harm. Though in one instance, as Halloween approached, a young woman in Reading, Pennsylvania, was arrested for falsely reporting a knife-wielding person dressed as a clown. And just prior to Halloween, the FBI identified a robber who, disguised as a clown, knocked over a string of banks in Ypsilanti, Michigan. Though incidents like these proved to be isolated, the New York Daily News sensationalized a “Nationwide Creepy-Clown Terror.” And such is the power of the Internet that news of frightening clowns shortly appeared in places as far-flung as Norway and New Zealand.

The hubbub prompted McDonalds to furlough their goofy trademark, Ronald. Target Corporation pulled clown masks from its stores. And when asked about evil clowns, the White House press secretary urged local authorities to carefully review “perceived threats to the safety of the community.”

It is easy to trace these extraordinary reactions to two sources: the first cultural, the second psychological.

The image of sympathetic clowns has been the rule in the United States, but this was not always and everywhere the case. Royal courts commissioned jesters—set off by garish costumes and often short stature—to grimace and speak the awful truth to power. (Provided they spoke it humorously...) The character Pulcinella, anglicized as Mr. Punch, brought slapstick mayhem to British puppet stages in the mid-17th century. In the late 19th century, the opera Pagliacci featured a murderously jealous but tuneful husband who dressed “in clown” for the title role. More recently, a spate of malevolent clowns appeared in films, sometimes comically, as in the 1988 feature Killer Klowns from Outer Space, but more often for horror’s sake, as in the 2012 feature A Cabin in the Woods. The Joker chillingly appeared in several Batman movies and comic books. And let’s not forget the real life serial killer John Wayne Gacy who rounded out the picture in the 1970s as he moonlighted, horrifyingly, as a birthday clown-for-hire.

The second wellspring of unease arises from a built-in revulsion to near-human representations—an instinctual, dreadful feeling of “the uncanny” that gathers as an embodied emotion at the backs of our necks. Some will find clowns’ fixed, painted-on smiles disturbing while others may shudder at almost-lifelike department-store manikins. Thoughts of zombies, re-vivified mummies, monsters sewed from spare corpse parts and sparked to life, undead vampires, and the assortment of ill-intentioned cyborgs, homicidal androids, evil automata, possessed puppets, and bad robots are such powerful generators of the uncanny that they have become stock characters in horror films. Think of the incarnations of Dracula, Frankenstein’s Monster, and The Terminator, or the alien robot, Gort, from the 1951 Cold War fear-jerker, The Day the Earth Stood Still. In a phenomenon much like today’s evil clown-craze mania, calls to police reporting UFOs surged dramatically after flying saucers invaded early-1950s science fiction flicks.

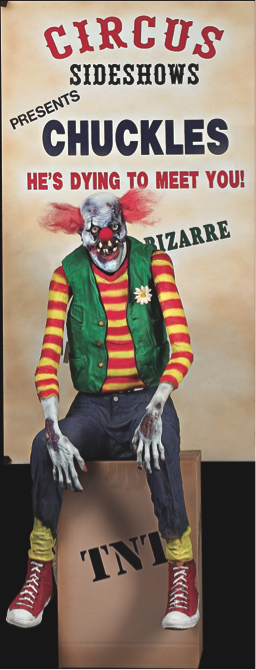

Usually, we play with scary images for the fun of it. Childhood friends of mine, Pete and Dave Gottschalk, once improvised spooky scarecrows for Halloween. (They also made a half-scale model of the Lunar Excursion Module, but that’s a subject for another blog.) Now, mostly all grown-up, they make a business of comic horror in their designs of life-sized, spooky animatronic figures. The sinister “Chuckles the Clown,” pictured here, is probably my favorite. These comics do us no harm, and because they make us laugh at horror and so defy it, they even do some good. Costumed up for Halloween, we’re better positioned to defeat fear of the dark.

But when fun teeters over the edge and plunges into the frightful, disquieting uncanny valley, as clown-phobics will, play comes to an end.

In 1841, the versatile Scottish poet, newspaper editor, and travel writer, Charles Mackay, wrote in his Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds that “every age has its peculiar folly—some scheme, project, or phantasy into which it plunges, spurred on either by the love of gain, the necessity of excitement, or the mere force of imitation.” Mackay’s observation of hilariously mistaken belief holds true today as public conversation swells with unreasonable fear. The timorous mood spreads unreasonably to Halloween. In an interview in the American Journal of Play, Hara Estroff Marano and Lenore Skenazy note that, ironically, chilling news reports of doctored candy notwithstanding, Halloween is the safest night of the year.

We’ve arrived at this juncture mainly because television news has blended with sensational entertainment to propagate fear. The small screen delivers threatening characters into our living rooms—apparitions of agents in black helicopters, political demons, followers of alien religions, and rapists speaking in foreign tongues. In fact, you are 35,000 times more likely to die of heart disease than from a terrorist attack. When future historians look back, they will likely label our time an “Age of Anxiety.” And they will be sure to shake their heads incredulously as they footnote the media-driven mania over evil clowns.