Anxiety

Two Shakes Of A Dog’s Tail

New research into how dogs interpret asymmetric tail-wags

Posted November 1, 2013

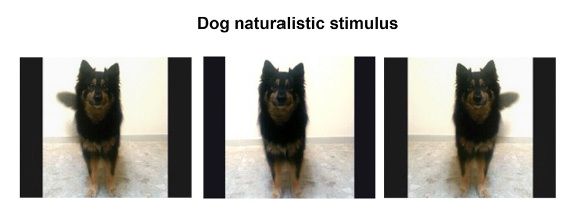

Stills from movies played to dogs

Dogs are outstandingly sensitive to human body language—they outperform all other species, including chimpanzees, in decoding our gestures. It has long been hypothesised that this ability evolved from the expertise that wolves, their ancestors, evidently possess in "reading" the body-language of other wolves. Now, a study reported by Siniscalchi and colleagues in the latest issue of Current Biology confirms that domestic dogs do indeed have a profound understanding, not only of our gestures, but also those of other dogs. When 43 pet dogs were shown movies of a dog whose tail was wagging to its left, their heart-rates increased and their behaviour indicated that they were feeling anxious. By contrast, when shown movies where the dog’s tail was wagging to its right, they became relaxed.

The study is intriguing, however, since it does not reveal precisely what—if anything—dogs are trying to signal when they wag their tails to the left or to the right. In a previous study the same team had found that the sight of an aggressive (“dominant”) dog triggered left-wags (controlled by the right hemisphere of the brain, the side which is thought to process emotional information, especially fear and anxiety). The involvement of the dog's right hemisphere in processing threatening stimuli was recently confirmed by a research team at the University of Lincoln, who found that dogs turn their heads to the left (implying right hemisphere control) when looking at a picture of an aggressive dog (and to the right when looking at a picture of a happy dog).

Yet in the new study, when the dogs saw the left-wags, they became stressed: this does not seem to be consistent with the idea that left-wagging is an admission of weakness or submission. Indeed, in research done at the University of Victoria in Canada, dogs were more likely to approach a lifelike robot dog when its 'tail' was made to wag left rather than right, rather than becoming anxious—the Siniscalchi study would predict the opposite.

Robot dog with a wagging tail

The inconsistencies between these studies may be due to the fact that some have presented movies to dogs, some have used still photographs, and others an actual dog. We cannot be entirely sure how the dogs are interpreting the movies played to them in the latest study; we can only say that they are reacting to them. Logically, they should be using the other dog's behaviour as a basis for deciding whether to approach or retreat. Thus (according to the Italian team’s previous paper) a left-wagging dog should be signalling "I'm frightened of you", yet the dog watching the film is reacting as if he's thinking "I'm frightened of YOU"!

That inconsistency suggests that the dogs may not perceive a dog in a movie as a potential partner for interaction, but if not, then what? Almost certainly not its reflection in a mirror, which seems to have little meaning for dogs. Another remote possibility is emotional contagion—as if the dogs that observed the left-wagging were interpreting it as having been triggered not by their own presence, but by the behaviour of a third, threatening, dog that they could not see.

Maybe the difference between a real dog and a 2-D movie is much greater for dogs than it is for us. That might explain why the study done with the robot dog produces a slightly more logical result—dogs approach a left-wag robot because they see it’s signalling that it’s feeling timid.

Currently, a significant gap in the studies seems to be that we don’t know what kind of dog would make another dog wag to the right—from their published data, the Italian team have only triggered right-wagging by exposure to people.

While there is considerable evidence from many different mammals that the two sides of the brain are used for different purposes, much of the detail still has to be hammered out—and dogs are no exception. However, given the ease with which their behaviour can be recorded, it will probably not be long before we understand more about why their tails sometimes go one way, sometimes the other.