Diet

Eat and Be Merry, for Tomorrow We Diet!

The feasting-and-fasting vicious circle is punishing and impossible.

Posted January 21, 2021

Feasting and fasting. Fasting and feasting. A vicious circle, hard task-masters, the ‘angel and devil’ on your shoulder’? Sometimes we feast before we fast, or we fast to prepare for the feast. Feasting and fasting take their toll and in our body-focused culture they are even more demanding than they were. Drink, eat, indulge at Christmas, and then detox, clean, revive, refresh and restore and New Year.

In this year’s strange lockdown Christmas, we are told to eat what we want, indulge in a festive tipple, and treat ourselves to Boxing Day treats because we deserve it. Days later, stories about New Year’s diets tell us what a mistake this was. We are “stepping into the new year with a heavier foot than normal,” “starting 2021 with a little extra weight on board.” We have to fix this sorry state of affairs, we need to fix our bodies, “follow these expert tips to get back on track after binge eating.” We need to control ourselves, bring our unruly muffin tops back into line, we might even make resolutions to try to keep us on track. A YouGov study on New Year’s resolutions confirms we’re in full-on fast mode: of the 19% of Britons making resolutions in 2021, the most popular three were about fixing the body; “doing more exercise or improving fitness” at 53%, “losing weight” at 48%, and “improving diet” at 39%.

The feasting and fasting vicious circle is punishing and impossible. The two bodies—the indulgent, luxuriating December body, and the early-rising, regimented January body—conflict. We can’t have both, and not in this order. We will fail at one or, more likely, both, and then how will we feel? Not great, these tweets suggest!

But so what, why does it matter? Especially if our December body is doomed to fail the test. It matters because our bodies have become our selves, meaning the too-tight waistband and non-conforming January body feel like failures of the self. As argued elsewhere this matters, it cuts deep, it leads to feelings of guilt about letting ourselves go, increased desire for plastic surgery, and harms like low self-esteem and body dissatisfaction.

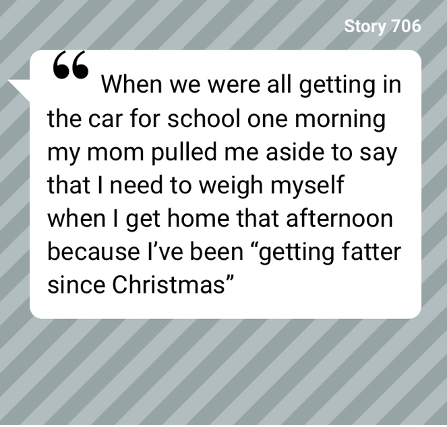

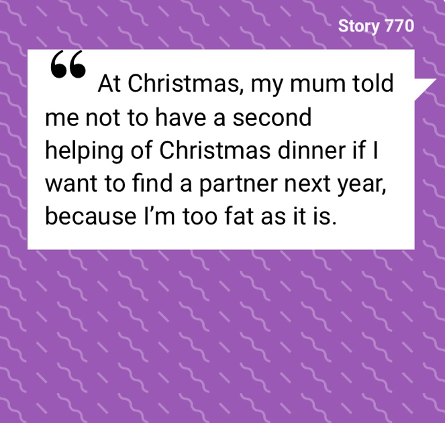

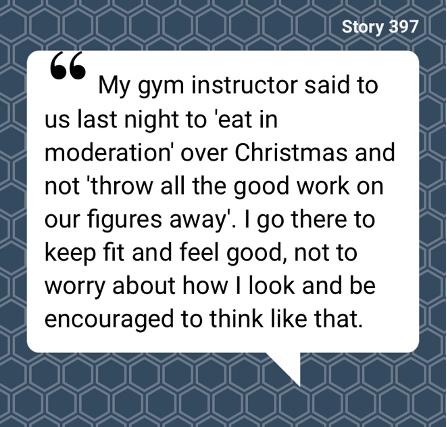

It’s bad enough that we feel bad, but this can be made worse with bullying and shaming comments. Lookism, discrimination based on looks, is shown in body-shaming comments—sometimes by strangers, but just as often by family and friends. We might be encouraged to indulge at Christmas but the body-shaming doesn’t stop, as these anonymous stories shared with the #EverydayLookism campaign show:

Indulge but don’t get fat. Enjoy but then punish yourself. We are bombarded with diet advice and adverts, and we internalise this. This is triggering for those who suffer eating disorders and nearly all of us have body image anxiety and dissatisfaction. If we’re going to make some resolutions, maybe we don’t want to make them about our bodies? Maybe we don’t want to measure who we are by how well we conform? Maybe we could be kinder to ourselves and others?

Maybe we could share the #EverydayLookism campaign? By naming lookism, we call out body shaming as discriminatory and harmful. In this brave ‘new pandemic year’ with so many pressures, let’s reflect on who we want to be, and how we want to treat others. If we want to live in a world where people are more than bodies let’s change the culture, think and act differently, let’s stop body shaming.

To find out more about the campaign, read the anonymous stories or to submit your own go to: everydaylookism.bham.ac.uk.

Authors:

Helen Ryland, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Department of Philosophy, University of Birmingham.

Jessica Sutherland, Research Assistant and Global Ethics Ph.D. student, Department of Philosophy, University of Birmingham

Heather Widdows, John Ferguson Professor of Global Ethics, Department of Philosophy, University of Birmingham