Psychiatry

We Miss Many Psychiatric Diagnoses

Disabling physical disorders are often associated with mental disorders.

Posted January 8, 2022 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- Clinicians and mental health professionals have been trained to expect patients with a mental disorder to express its psychological symptoms.

- Patients with common chronic physical diseases, such as cancer or chronic pain, have high rates of mental illness.

- Unfortunately, these patients often do not express the psychological symptoms needed to diagnose the co-occurring mental disorder.

- All providers need to actively inquire about a mental disorder in patients with disabling chronic physical symptoms of any origin.

In patients with chronic, disabling physical symptoms, an unrecognized associated mental illness often co-exists. These patients typically do not offer their clinicians the expected psychological symptoms needed for a diagnosis, instead focusing only on their physical issues.

I propose that disabling chronic physical symptoms represent a “red flag” that should prompt clinicians to actively inquire about psychological symptoms when patients don’t mention them. Only by diagnosing the co-occurring mental illness can patients benefit from its treatment.1,2

My previous post emphasized that primary care providers are untrained in mental disorders. I’ll discuss one aspect of this lack of training, one that also applies to mental health professionals' training.

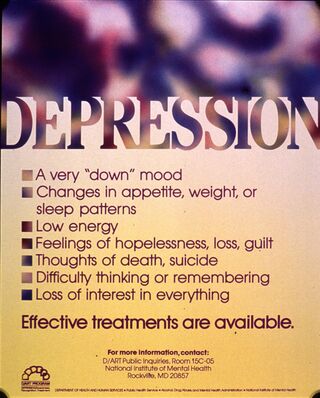

Primary care clinicians, psychologists, psychiatrists, and other providers seek a mental disorder diagnosis only when a patient presents with psychological symptoms, such as sadness, agitation, worry, or hearing voices. Indeed, modern psychiatry textbooks foster this almost exclusive interest in psychological symptoms, typically addressing the physical aspects of mental illnesses with only a brief chapter on the various DSM somatoform disorders towards the end of the book.

Understanding the role played by physical symptoms in mental health diagnoses can greatly increase recognition (and treatment) of mental disorders, the most common health problem in America.1

The first issue in identifying mental disorders in patients with incapacitating chronic physical symptoms is that they may come in one or both of two broad diagnosis categories. Clinicians more often overlook the mental illness in the first one but commonly do so as well in the second one.

1. Some incapacitating physical symptoms represent an organic disease with a known pathophysiological basis. Clinicians diagnose these patients by standard history, physical exam, diagnostic testing, and consultation with specialists. Any debilitating physical disease can cause a mental disorder—or vice versa:

- A chronic physical disease leads to a mental disorder, for example, enervating emphysema, sickle cell disease, or cancer leads to depression, anxiety, or substance abuse.

- A mental disorder leads to chronic physical disease. For example, alcoholism leads to incapacitating cirrhosis of the liver, or depression leads to overeating and diabetes with debilitating painful neuropathy.

2. Other immobilizing physical symptoms have no disease explanation after an investigation by the same means above. This condition is called medically unexplained symptoms, and it is extraordinarily common. Many patients with chronic pain, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic fatigue fall into this category.

As with organic diseases, the severe physical symptoms may precede or follow depression, anxiety, or substance use problems.

Whether the disabling symptoms are medically explainable or not makes no difference—it’s the interference with one’s life that correlates with a co-occurring mental illness.

Why then do these physically ill patients with a mental illness not express psychological symptoms, focusing instead on their physical complaints? Without key psychological symptoms, diagnosing a mental illness is nearly impossible.

- They stigmatize themselves for having emotional or psychological problems.

- They are unaccustomed to discussing personal issues in medical settings.

- They believe that physicians will be uninterested, even critical (stigma).

- They lack awareness of their psychological symptoms.

Untrained primary care providers understandably seek a disease diagnosis and treatment for their patients with disabling physical symptoms—but they go no further to identify one of the commonly associated primary care mental disorders: depression, anxiety, and substance abuse.1

The remedy: physicians and other clinicians need to actively inquire about psychological symptoms in patients with chronic, disabling physical symptoms, whether they have a disease explanation or not. These patients usually exhibit major impairments in their daily lives—and this causes their mental illness.

For example, when someone with severe heart disease, chronic pain, emphysema, diabetes, or irritable bowel syndrome can no longer go to the movies, play cards with friends, visit grandchildren, work, have sex, go to church, travel, or play golf, it’s not surprising that they develop depression, anxiety, or substance abuse.

While any type of physical symptom may be chronic and disabling, it’s the incapacitating feature that bespeaks an underlying mental illness, not the particular symptoms or whether an actual disease exists.

The importance of physical symptoms in mental illness goes beyond diagnosis. Treatment is far more challenging when physical and mental disorders co-occur than treating a mental disorder without a comorbid physical problem. Indeed, most find that treating the comorbid physical symptoms (severe pain) is far more difficult than treating the mental health problem itself (such as depression).

Although treatment is beyond the scope of this discussion about diagnoses, I provide some details in a previous post. And my Michigan State group has identified (from randomized controlled trials) a comprehensive, evidence-based model for the integrated care of patients with combined medical and psychiatric disorders—the Mental Health Care Model.1

I’m also citing another more general resource that I've found helpful to enhance doctor-patient communication.3

In conclusion, to increase the number of mental health diagnoses, I propose we view debilitating, chronic physical symptoms as a “red flag” for an underlying mental disorder even if patients do not offer psychological symptoms. Clinicians must understand that burdensome physical symptoms, whether an explanatory disease exists or not, are frequently associated with underlying mental health problems.

They should then ask about the diagnostic psychological symptoms found in psychiatry textbooks to pin down a specific mental illness diagnosis—depression, anxiety, and substance use most common in primary care—thus enabling a critical new treatment modality.

The clinician would be taught to ask, for example, “In someone with as much pain as you have, keeping you from even going to church, I wonder if you might also feel somewhat down—how’s your mood, your sleep, your enjoyment of life?”

References

1. Smith R, D'Mello D, Osborn G, Freilich L, Dwamena F, Laird-Fick H. Essentials of Psychiatry in Primary Care: Behavioral Health in the Medical Setting. New York: McGraw Hill, Inc; 2019

2. Smith RC. It's Time to View Severe Medically Unexplained Symptoms as Red-Flag Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2011520.

3. Ko C. How to Improve Doctor-Patient Communication--Using Psychology to Optimize Healthcare Interactions. New York: Routledge, an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group; 2022.