Procrastination

Combating the Creative Barrier of Precrastination

Getting time on your side in the creative process.

Posted June 13, 2019 Reviewed by Matt Huston

Postponing a decision or an action—putting it off until a later time or a different day—is sometimes both wise and necessary. Despite this, we all know that sometimes we postpone too long; we repeatedly put off making a needed decision or taking a required action. Tomorrow, we say, tomorrow; I'll do that tomorrow. Or later, I'll decide. And this postponing can land us in the troubled deeps of procrastination, where we rob ourselves of the needed time to fully and thoughtfully realize our creative aims or other goals.

Painful and ensnaring as procrastination can be, have you ever thought that we might be prone to an opposite form of time-based error—when we make decisions or take actions too soon, over-hastily and immediately, before we should?

Precrastination: It's a Thing

Although we're all familiar with procrastination, research has uncovered that in many situations we may engage in a form of "precrastination"—getting something done quickly just to get it done—that can be surprisingly contrary to good sense.

First discovered in research looking at the decisions that people made in a simple weight-carrying task, the researchers couldn't quite believe what they observed.

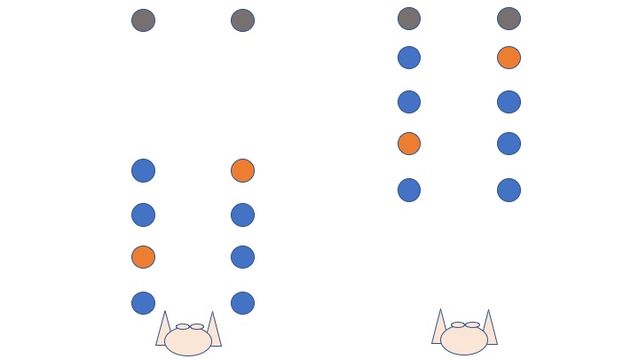

In their first experiments, participants in a long lab room were asked to carry one of two plastic beach buckets to a platform farther down the room from them. The two buckets were placed by the researchers in positions such as those shown in the diagram below.

Participants were instructed to pick up one of the two orange buckets (pictured with orange dots) and to carry it to the platform at the end (grey dots). They were asked to walk down the room without stopping and to "do whatever seemed easier"—either to pick up and carry the left orange bucket to the left platform with their left hand, or to pick up and carry the right orange bucket to the right platform with their right hand. Each of the orange buckets was situated such that its handle was upright and readily grasped.

The researchers had anticipated that participants would choose to pick up the bucket that was closest to the platform, so that they'd need to carry the bucket forward the shortest distance.

But this was not what they found.

Instead, participants most often picked up the first bucket that they passed (regardless of whether it was on their left hand or their right hand)—and so they ended up having to carry the bucket farther.

It wasn't that participants didn't know how heavy the buckets were. All participants were given the opportunity to lift the buckets at the start of the experiment, so they knew how heavy they were (empty, or filled with 3.5 pounds or even 7 pounds of pennies in different experiments). They also took part in 16 different trials with the buckets in 16 different arrangements. Still, this pattern, of most often choosing to pick up the first bucket they passed and therefore having to lug the bucket a longer distance, was repeatedly found.

Why did participants most often choose to pick up the bucket that they first approached, rather than the one farther down the room, so that they ended up carrying the bucket farther than was necessary?

Asked by the experimenters after they had completed all of the trials, the participants nearly always gave the same answer, saying something to the effect of, "I wanted to get the task done as soon as I could." They gave this reason when, in fact, the task would require the same amount of time regardless of whether they picked up the first and closest bucket after they started (then having to carry it farther) or picked up the second bucket (then having to carry it a shorter distance).

But then: Why would participants feel that they were getting the task done sooner? Hastening to complete one part or subgoal of their task—that of grabbing and lifting the bucket—seemed to make completion of the full task closer. Grasping and lifting the first or nearer bucket also allowed the participants to clear their working memory of that subpart of their overall task.

Remembering to do an upcoming task (what is called "prospective memory") is mentally demanding. It seemed that the relief of clearing from working memory even the small subtask of picking up one of two objects was sufficiently attractive (throwing off a small mental load) that it offset the additional physical effort required to carry the picked-up object a farther distance. Participants "precrastinated" even though it required greater physical effort.

But if there were noticeably greater cognitive demands linked to the carrying task, then a different outcome was observed. When, in a new experiment, participants were instead asked to carry cups filled with water that could be easily spilled, and were asked to prevent any spilling (placing high demands on their attention), then participants rarely chose to pick up the nearest object. Now participants most often chose to pick up the farther cup, minimizing the amount of cognitive effort they needed to expend to carry the brim-full cup with minimal spillage to the final platform.

Deferring Decisions in Creative Endeavors

In more complex creative endeavors, it can be challenging to wait and to defer taking a decision on how a subtask should be completed because deferring a decision feels like we're not making progress. Yet—as data from both self-reports of creative individuals and an in-depth case study of a musical composer suggest—deferring a creative decision (that is, avoiding precrastination) can sometimes allow us to take in new knowledge, expanding our creative problem-solving mindset, and in turn open the opportunity for a new influx of creative ideas.

Let's take a closer look at the in-depth case study of a professional Finnish composer (let's call him Composer Z) creating a novel musical composition.

Early on, Composer Z had a broad sense of what his new extended musical piece should be, but his central creative idea was still vague and fuzzy. It did not offer him straightforward guidance in the many immediate compositional decisions he needed to make. Yet despite his uncertainty and despite deferring more global or overarching decisions, Composer Z did not stop working entirely.

Rather, "leaving an increasing number of empty bars in the score along with unanswered problems," Composer Z moved ahead to different parts of the musical score, as he "persistently invented and experimented with his musical materials; he tested, associated, theorised, juxtaposed, applied and developed his ideas into new situations" (p. 224). All the while he was continuously trying to relate what he was now learning to what he already had learned about the evolving musical piece, and trying to use it to further clarify (learn, see, feel) where he wanted it to go in the future. "The composer learned as he composed and composed more as he learned more." (p. 224)

After this extended process of deferred decisions, Composer Z suddenly reached a critical point where his working and writing changed. Rather than hesitation and confused and fragmented moves, his creative working now became highly fluent. He made quick and effortless decisions that seemed to him "surprisingly intuitive." These were not arbitrary choices, but appeared to be—from a music analysis point of view—"logical deductions based on nearly all the composer’s actions from the very beginning of the process" (p. 224).

Putting It All Together

In your creative process and innovative endeavors, do you allow yourself (and your team) to engage in "purposeful decision deferral"—as Composer Z permitted himself to do during the creation of a new and challengingly innovative work—so as to avoid early stage commitments that are poorly grounded in your understanding of what a project could be? Are you (sometimes) too eager simply to "do" subtasks, rather than to "fulfill them" (that is, "fully fill" them, with all the new understanding and knowledge that you will have gained by deferral)?

Purposeful decision deferral is not an excuse to "do nothing." Deferring the moment of decision is, rather, a way to gain a welcome window of time during which we can further explore and experiment with adjacent or alternative aspects of a problem space. Purposeful decision deferral—that is the opposite of precrastination—is a way to give ourselves time to reconfigure how we're thinking, and time to inadvertently and often indirectly learn more about what our creative problem (really) needs. Yet it's tricky: If we're not fully attuned to where we are in our thinking/experimenting/exploring, purposeful decision deferral could be protracted beyond what is needed.

Things to Think About

- If you're feeling a sense of urgency to get something done, where is that urgency coming from—is it real? Is it something that you're generating—out of habit? Out of a wish to keep your mind and thinking space uncluttered? Or out of a desire for that "small burst of positive reward" you feel when you (mentally, or physically) check another item off of your to-do list?

- If one of the reasons that you precrastinate is that you find it rewarding that something is "just done" (now scratched off your to-do list), could you change your take on what is rewarding and instead find rewarding experience in a different way, for example, finding reward in being thorough, thoughtful, and creative?

- Are you assuming that you have to work on a project in a set order, from beginning to end? Could you switch it up a little and work on a different part of your project so as to let new information in, and give yourself some more room for further experimentation and exploration?

- In your past creative endeavors, have you more often regretted postponing doing something (procrastination) or doing something too hastily, without sufficient forethought or integrated understanding (precrastination)?

- On the to-and-fro swing of a creative endeavor, when should you give yourself an extra push, and when should you let yourself glide, absorbing more of where and how you are, in your experience or creative endeavor?

LinkedIn Image Credit: YAKOBCHUK VIACHESLAV/Shutterstock

References

Cohen, J. R., & Ferrari, J. R. (2010). Take some time to think this over: The relation between rumination, indecision, and creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 22, 68–73.

Fournier, L. R. et al. (2019). Which task will we choose first? Precrastination and cognitive load in task ordering. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 81, 489–503.

Pohjannoro, U. (2016). Capitalising on intuition and reflection: Making sense of a composer's creative process. Musicae Scientiae, 20, 207–234.

Rosenbaum, D. A. et al. (2019). Sooner rather than later: Precrastination rather than procrastination. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28, 229–233.

Rosenbaum, D. A., Gong, L., & Potts, C. A. (2014). Pre-crastination: Hastening subgoal completion at the expense of extra physical effort. Psychological Science, 25, 1487–1496.