Stress

Stress and Health: Reversing the Health Impacts of Stress

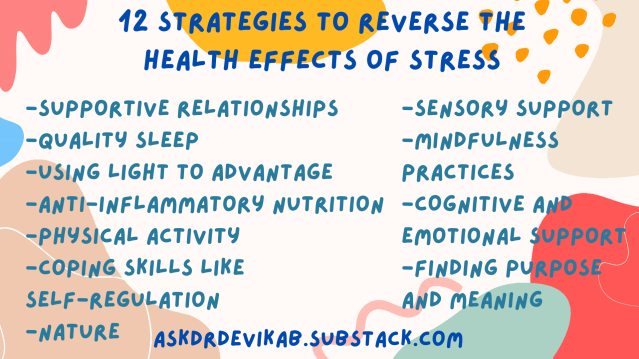

These evidence-based strategies can reduce and reverse the effects of stress.

Updated September 22, 2023 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Repeated, prolonged, or excessive activation of the stress response can lead to wear and tear on our bodies.

- Certain evidence-based tools can reverse the impacts of stress on our brains, hormones, and immune systems.

- Using these tools consistently—even in small doses—can prevent and even reverse health effects of stress.

By Rachel Gilgoff, M.D., FAAP, and Devika Bhushan, M.D., FAAP

This post is Part 3 of a series. Previous posts covered what you need to know about stress and how to turn off the stress response.

Going through something stressful—like losing a loved one or even the wear and tear of constant stressors like caregiving responsibilities or discrimination, for example—can affect any of us over the long run in sometimes unexpected ways.

You’ll recall that the stress response can be lifesaving, like when we face a predator. However, repeated, prolonged, or excessive activation of the stress response can lead to wear and tear on our bodies. It can affect our brains, hormones, immune systems, and even our genes—and potentially lead to poorer mental and physical health.

The flip side is that we have ready access to evidence-based tools that a) can help us turn off the stress response in the moment—and b) can even reverse the longer-term health impacts associated with a stress response that has been activated over and over again (below)—so we can each feel our very best.

These strategies help us do exactly that. They apply to both adults and kids; where relevant, we’ve included adaptations for children, marked with a ^.

Admittedly, we do not all have equal access to the energy, time, and space it takes to enact these strategies—structural constraints matter a lot. But the beautiful thing is that many can provide benefits with whatever space we do have—even in a few minutes, we can see nourishing impacts of time outdoors or mindfulness.

Healing tools and strategies

Supportive relationships

Connection and safety through supportive, nurturing relationships can make all the difference when we’re struggling through something stressful. Though it can be hard, especially when we’re not feeling our best, reach out to those who bring you joy and meaning.

For adults:

Connect with loved ones regularly. Create opportunities for high-quality time together, like watching a comedy show (including online), cooking or eating together, or just talking through what’s on your mind, or making a quick call or sending a text saying you miss someone or sharing a favorite memory or something you love about them can be meaningful for both parties.

Don’t be afraid to ask for help if you’re going through something tough, including for basics like child care. When you’re feeling better, you’ll be able to give back to your community in all the ways that you’re receiving help just now.

Consider reaching out to community-based services for help with basic needs

For children:

- When possible, reassure your child that they're safe. You can do this with words, but also with hugs, high-fives, and practical supports like a tent in their room or a “cozy corner.”

- Take 15 minutes without cellphones to follow their lead in an activity of their choice.

- Share activities like walks, cooking, dancing, and playing silly games.

- Tell your child what you love about them.

- Build routines like reading a bedtime story or having dinner together every night.

Quality sleep

Sleep is fundamental to recovery and health, and it can be one of the first things to suffer when we’re stressed. Worries may keep us awake or cause restless sleep. Some things to try:

- Be strategic about exposure to light and dark (below).

- Try going to sleep and waking up around the same time each day.

- Use comforting bedtime routines like: reading, journaling, listening to calming music, relaxing smells, deep breathing or meditation, and stretching or yoga.

When children are stressed, they may need more flexible bedtime routines and help falling asleep. Comforting items and relaxing routines can be helpful, such as a night light, relaxing smells, favorite toys, a weighted blanket (if child is older than 12 months), music, mindfulness practices, reading, and journaling.

For children experiencing separation anxiety at night (common after stressful or traumatic events), consider leaving items that give extra reassurance:

- Love notes stuck around the bedside.

- Pieces of clothing that smell like you.

- For some children, consider staying in the room while they fall asleep or even letting them sleep with you for a short while as they process the stressful experience.

Light

During the day, especially early on, get direct exposure to natural sunlight. This helps regulate sleep, mood, and immune function, among other systems.

At night, reduce exposure to screens and artificial lights by dimming them. You can even use blue light-blocking glasses to limit exposure to the blue wavelengths of light that wake the brain up by turning off the sleep-inducing hormone melatonin and disrupting sleep.

Balanced, anti-inflammatory nutrition

Stress can increase inflammation and lead us to over- or under-eat or crave foods high in fat, salt, and/or sugar. Knowing this can help us be kind to ourselves and our kids when they reach for the brownie and the potato chips—and to help ourselves in those moments.

- Skip the juice and soda and drink water instead.

- Reduce foods that increase inflammation such as processed food and white (simple) carbohydrates.

- Make it easier to reach for healthy, high-fat or high-sugar foods like nuts, avocados, cheese (in moderation), and fruits.

- Increase the availability of vegetables (fresh or frozen) at snacks and meals.

Physical activity

Regular exercise can be a powerful way of releasing extra stress energy and counteracting the stress response. Any amount of exercise—even a few minutes—is helpful. Several times a week, try to get up to 30 to 60 minutes a day, and it doesn’t have to be all at one time. A few pushups between Zooms, getting off the bus a few stops early to get in those extra steps, or some bedtime yoga: it all adds up.

Bottom line: Get your body moving whenever you can and, ideally, try to sweat and get your heart rate up. Consider:

- Jumping jacks, squats, or bridges.

- A game of basketball or other fun team sport.

- Dancing to a favorite song.

- Martial arts.

- Yoga.

Getting out in nature

Time outdoors can be calming for the nervous system and pairs well with exercise—and with spending time with others. We love doing a "walk and talk" outside with friends.

- Check out a local park or a playground.

- Walk around the block.

- Hike.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness practices can help calm stress physiology, improve self-regulation, and increase self-compassion and empathy. Try:

- Meditation or mindful breathing.

- Focusing on each of the five senses while sitting still.

- Watching the sunset or sunset—or clouds drift on a clear day.

- Practicing gratitude

- Using free online videos and apps for kids and adults.

- For kids: belly breathing with Elmo, with Rosita, or 4-7-8 breathing.

Sensory support

Soothing, rhythmic sensory activities can help reset the way stress is stored in our nervous system and body. Consider:

- Massage.

- Music.

- Movement, especially rhythmic activities like dancing, walking, jumping, swinging, rocking, swimming.

- Occupational or physical therapy.

Finding purpose and meaning

Especially when we wonder, "Why did this happen?" and "Why me?" activities that help us make meaning of our experiences can be really helpful in grounding us and guiding us forward.

Consider:

- A spiritual practice or connecting to a religious community.

- Helping others through service or volunteer work.

- Finding a calling or purpose, including helping fix systemic injustices.

- Becoming a peer supporter.

Cognitive and emotional support, including coping skills

We can better cope with stress once we learn specific skills to manage our more difficult feelings and behaviors, including how to set boundaries and self-regulate.

Consider when you might need to seek extra help or take a period of time away from work or school to attend to your health.

There’s no shame in needing extra support through mental health therapy for yourself or a child or loved one. Therapy can be super valuable in helping to practice the tools presented here and to develop additional coping skills. Depending on your needs, consider exploring work with a therapist or other supports.

Children going through a stressful experience may benefit from additional supports through school-based 504 plans or Individualized Education Programs (IEPs), speech and language therapy, tutoring, and specific therapies like art therapy, play therapy, or family therapies like parent-child interaction therapy, and child-parent psychotherapy.

To find a therapist, please visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

A version of this post also appears with the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Rachel Gilgoff, MD, FAAP is an integrative medicine specialist, child abuse pediatrician, science writer, researcher, and mother.