Education

The End of Rural Communities: Why Young People Leave

Many youth prefer their rural homes but are forced to leave for work and school.

Posted November 22, 2015

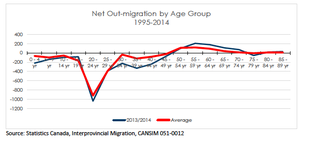

Over the holidays many young people will return to their rural communities for a visit. Fewer and fewer, though, are choosing to live in the small towns and on the farms where they grew up. I can see it first hand. I live in a city that has been building apartments and townhouses at a remarkable rate even as we witness the rapid depopulation of the rural communities less than a two hour drive away. A recent task force has been looking for answers, though I’m not sure they’re any closer to a solution despite the lengthy consultations. Net out-migration from our small towns and villages is increasing, especially among youth ages 20-29. They leave for work and education. Sometimes they leave for relationships they form over the Internet. They come back to retire, or when their parents pass away. In any case, young people’s most productive years are spent in cities where they will pay taxes and take on mortgages.

Remarkably, though, a lot of the young people who leave would prefer to stay in their rural communities. Recent research by a doctoral student who works with me at the Resilience Research Centre, Nora Didkowsky, is showing us that rural youth are caught in a complicated set of negotiations. Many of the young people who feel forced to leave would choose a rural lifestyle over an urban one. They like the open spaces and the kinds of recreational activities available beyond concrete jungles. They appreciate the sense of community that exists in many small towns. They like the daily contact with nature and waking to birdsong or the mooing of a cow. They like the pace of life and the values people hold to. They want less stressed lives and safe places to raise a family.

But they leave just the same. Unemployment and economic stagnation push many out. A minority are pulled by wonderful opportunities to learn new things and advance in their chosen trades. They only stay back, according to Didkowsky, where there is ‘youth-place compatibility’, a positive pattern of adjustment that lets young people experience the advantages of rural living without excessive compromise of their education and employment goals.

For many young people who remain in rural communities, it means long commutes to post-secondary institutions in nearby cities or residing away from home for extended periods of time. It almost always means owning their own car and continuing to live at home with their parents because they can’t afford a place of their own.

While a surprising number of young people make these adaptations because they love where they grew up, many others are forced to leave by a lack of opportunities to earn a living. Governments have proven remarkably thin on solutions. The one major recommendation of a group working for my provincial government was economic development in rural areas driven by private sector investment. As obvious as that sounds, it will take a lot of creativity to make it happen.

New industries that emphasize green technologies could help re-populate the countryside by allowing young people to work where the energy is produced (solar and wind farms, biomass facilities, etc.). The Internet has great potential to allow the creative class to leave the cities, and indeed many states and provinces are now investing to make high speed Internet accessible and affordable in even the most remote areas of our countries as a solution to depopulation.

We will also need to offer young people in small towns consistent quality services. Tele-health is making it far more economical to sustain community-based health care centers, and of course the dramatic increase in online education programs from our best universities is making getting a degree much more accessible.

None of this will matter, however, if the jobs don’t follow. Private enterprise is key, but government stimulus is also needed to even the playing field. I’m not talking about silly investments in large-scale initiatives that frequently go bust. Way too many call centers took government handouts and then closed shop quickly afterwards. I’m talking about tax incentives that are sustainable for rural businesses or guaranteeing rural businesses cheaper energy prices. Initiatives like these make rural areas attractive to investment. Ironically, they also challenge the more conservative, anti-government beliefs held by many who live communities that are shrinking.

We are really talking about how to make our rural communities resilient to changing demographics and a mobile youth population. If I’m learning anything from my colleagues who are researching this problem it’s that young people would prefer to live and work in rural communities if they could find a way to sustain a reasonable quality of life. Not every child wants to leave the farm. In fact most feel a deep sense of connection to their rural communities even if their depleted bank accounts force them to leave.

I’m not a romantic, however. Rural communities will be shuttered unless we accept the economics of place. Every small town cannot sustain its own 24-hour emergency room or post-secondary institution. We will need to think logically about the best way to provide services. But we also need to invest in the solutions like high speed Internet and cell coverage, good roads and tele-health care systems. We need to make it possible for jobs to migrate beyond our cities, and in the process, make it possible for our young people to migrate back to where many feel a sense of place and purpose.