Neuroscience

Nervous System Connections with Treatment and Malfunction

Emotional and movement control may be reflected in neural connectivity studies.

Posted October 8, 2020

When clients ask me whether cognitive behavioral therapy to help control anxiety or anger can “rewire” the brain, or change connections within it to function in a better way, I don’t say it’s impossible. That is because of research on stroke rehabilitation I began following a few years ago by Harvard-affiliated neurology researchers and on a 2020 study on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The stroke rehabilitation research utilized a method of brain stimulation from outside the scalp, without surgery, called transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), in patients with impaired movement after a stroke. Based on prior neuroscience studies, Drs. Xia Zheng and Gottfried Schlaug in 2015 reported that this stimulation over only 10 days focused on the movement command center, the motor cortex, when combined with physical therapy, led to improved hand movement when compared with a control group. Moreover, brain imaging showed changes in the long nerve fibers, also called axons, that send impulses downward from the motor cortex to the spinal cord nerve cells that control muscle movement, changes in structure that suggest more effective functioning.

As an analogy, imagine how fast it would be to drink a soft drink with five drinking straws bundled together, compared to two straws, one of them bent. The five straws would let you slurp up the drink much faster. In this analogy, the straws are something like the nerve fibers that carry impulses or signals from one end to the other.

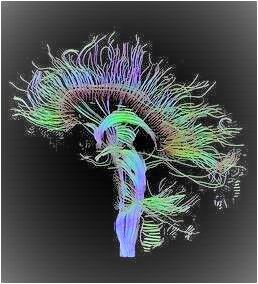

In the brain study, a complex offshoot of magnetic resonance brain imaging called DTI, for Diffusion Tensor Imaging, estimates the parallel orientation, myelin insulation surrounding the nerve fibers, and integrity of the nerve fibers bundled together in major pathways from the motor cortex to the spinal cord nerve cells that control movement. The electrical stimulation coupled with physical therapy appeared to improve the patient’s arm and hand movement as well as the structure of these connections.

This is not medical advice. If someone shows any stroke symptoms, “even if the symptoms go away, call 9-1-1 and get the person to the hospital immediately,” according to the American Heart Association website.

A more recent review of nerve connectivity published in 2018 by Woo Suk and colleagues found changes in nerve connections or connectivity in a number of neurological problems and treatments. For example, the authors reported that neural connectivity estimated by the DTI method has been successfully used to evaluate the effect of rehabilitation therapy, this time after training of arm and hand movement with robotic devices. The results showed that the number and length of the movement-controlling nerve fibers increased significantly after 8 weeks of training.

From neurology to psychology is a big jump, but we can focus on the role of the amygdala, a small structure about the size and shape of an almond, in remembering and processing threatening emotional situations. It is an important part of a network underlying the fight, flight, or freeze response to threats. This structure is normally kept under control by the most highly evolved cerebral area, the prefrontal cortex.

What if that control is impaired? It has been generally understood that loss of this control can affect the symptoms of traumatic brain injury and of post-traumatic stress disorder, such as over-vigilance, memory flashbacks, anger outbursts, and other erratic behaviors.

In summary, the prefrontal cortex normally keeps the amygdala operating normally. But if it loses control, emotional memories and reactions can get out of hand. In fact, when I spoke to Roger Pitman, M.D., Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and an internationally recognized researcher, teacher, and clinician focusing on PTSD, he told me by phone several years ago, "probably the best-documented findings in PTSD show underactivity in the prefrontal cortex."

To continue with this concept, in psychotherapy, especially cognitive behavioral therapy, we attempt to understand the connections between thoughts, emotions, and behavior, and to use such methods as cognitive restructuring or re-framing to modulate overly emotional or impulsive reactions, either of anxiety or of anger, associated with amygdala functions. Such overreactions are often thought to involve impaired connections between areas in the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala.

A recent study (2020) by Delin Sun from Duke University and colleagues analyzed such connections in military veterans diagnosed with PTSD. They measured functional connectivity between brain centers by analyzing how neuronal activity varies from one center to another based upon localized blood oxygen level when 25 military veterans with PTSD reacted to unpredictable, mild shocks during an action game compared to 25 volunteers in a control group without PTSD.

The authors found that the control group reported less anxiety and showed more functional connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala on the left side of the brain. The results appear consistent with the importance of prefrontal-amygdala connections both in PTSD and in resiliency after stress, but open for discussion the one-sided nature of the results and the results of effective treatment for PTSD, which was not part of this research.

What if connections from the prefrontal cortex or other more evolved areas of the brain to the amygdala could be strengthened to function in a more adaptive way by effective forms of psychotherapy?

There are reports of enhanced connectivity between other brain centers after cognitive behavioral therapy for other disorders. Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is an example. For example, children and adolescents with OCD who responded well to such therapy showed greater post-treatment connectivity in the brain's left hemisphere between prefrontal areas and the angular gyrus, a region seen in a side view of the brain surface, that is associated with the ability to read, write, an do arithmetic among other functions, according to Marilyn Cyr and colleagues (2020).

This is mostly uncharted territory. It is not meant to support impressions from other types of brain imaging, or for untested forms of brain mapping or stimulation not based on evidence. But for patients with problematic traits like excessive anxiety or poor control of anger, it suggests the possibility that psychological therapy might enhance connections within the nervous system in a more adaptive way, much like the connections found in neurological treatment and disorders.

References

Zheng, X. and Schlaug, G (2015). White matter changes in descending motor tracts correlate with improvement in motor impairment after undergoing a treatment course of tDCS and physical therapy. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9: 229.

Tae, W.S. and others (2018). Current clinical applications of diffusion-tensor imaging in neurological disorders. J. Clinical Neurology 14 (2).

Lavine, R. (2012). Ending the nightmares: how drug treatment could finally stop PTSD. The Atlantic.com, Feb. 1.

Sun, D. and others (2020). Threat-induced anxiety during goal pursuit disrupts amygdala-prefrontal cortex connectivity in posttraumatic stress disorder. Translational Psychiatry 10.

Cyr, M. and others (2020). Altered network connectivity predicts response to cognitive-behavioral therapy in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 45: 1232-1240.