President Donald Trump

A Provocative Psychological Analysis of Trump by a Trump

What we can learn from Mary Trump’s new book about the president’s inner life.

Posted July 15, 2020 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

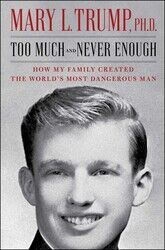

Child abuse is often the experience of too much or not enough, writes Mary Trump, Ph.D., in her just-published book Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created The World’s Most Dangerous Man.

Her uncle, President Donald Trump, had both too much and not enough in childhood, suggests Mary Trump, who has a doctorate in clinical psychology and has taught graduate courses in psychology.

The fourth of five children, Donald Trump was two when his mother was hospitalized for six months for multiple surgeries. Her absence at that critical age only amplified what Mary Trump recounts as a regrettable lifelong lack of emotional presence in Donald’s mothering.

“She was the kind of mother who used her children to comfort herself rather than comforting them. She attended to them when it was convenient for her, not when they needed her to,” writes Mary.

Whereas his mother was needy and “prone to self-pity and flights of martyrdom,” Trump’s father seemed devoid of emotionality or empathy. To Trump's father, Fred, neediness of any kind meant weakness.

Humiliating his children, sowing divisiveness, and bestowing money were Fred Trump's love languages. Mary Trump describes Fred as a “high-functioning sociopath” who “seemed to have no emotional needs at all.”

“I never saw any man in my family cry or express affection for one another in any way other than the handshake that opened and closed any encounter,” she writes.

Having a depleted, absent mom and a sociopathic father left Donald lacking any model for empathy, vulnerability, and reciprocity. In fact, such qualities were dangerous in the Trump family. Empathy had no value or upside. “My uncle does not understand that he or anybody else has intrinsic worth,” she writes.

What mattered in the Trump family was wielding power and making money. Of utmost importance was gaining Fred’s approval, which was capriciously given and unevenly applied.

Donald Trump chose to mimic his father: shunning neediness, suppressing most emotions, and bullying and humiliating others while taking credit for both his and others’ successes. Admitting failure or fault would be seen as intolerable acts of weakness.

This cascade from childhood deprivation and over-empowerment to an adulthood personality disorder that Mary Trump describes is all too familiar to therapists who, like myself, work with narcissists.

While I am not diagnosing Donald Trump, Mary Trump says that based on her lifetime observations of him from both near and far, President Trump meets all nine of the DSM-V characteristics of Narcissistic Personality Disorder.

In addition, she writes, Donald Trump may also have antisocial and dependent personality disorder traits along with possible learning disorders that can affect mood, behavior, and cognition.

As therapists, we know that hiding and denying deep feelings of early abandonment and shame can exact a terrible toll.

Rage can seethe. Fear and sadness are denied. Other people may be viewed as disposable. A ravenous hunger for approval, to compensate for the emptiness within, may gnaw, unquenchably, 24/7.

Mary Trump seeks to connect Trump’s upbringing to his playbook in his public life. The president needs affirmation. If it is not forthcoming, heads will roll and tactics will escalate. Any feelings of powerlessness are displaced, with the weak and vulnerable becoming targets. When humiliated, Trump may move into alternative realities, like drawing a fanciful projected path of a hurricane with a sharpie.

He also tends to dehumanize women and men alike, writes Mary. She recalled numerous family dinners at which her uncle spoke of women who were “ugly fat slobs.”

She recounts an exchange 19-year-old Donald had with a 22-year-old female friend of his older brother Freddy. Donald, fascinated with the older woman, told her he was disappointed in her choice of boarding schools.

She responded: “Who are you to be disappointed in me?” The woman recalled that Donald’s idea of flirting seemed juvenile, as if by insulting her and acting superior, she would somehow find that attractive.

At the same family dinners, Donald would label other men as “losers,” reflecting his father’s view that “in life, there can only be one winner, and everybody else is a loser.”

Mary Trump places prime importance on how seeking his father’s approval motivated Donald. And she offers her interpretation of his seeming affinity for dictators like Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong-un. They bear “more than a passing psychological resemblance” to his father, she argues.

“Every time you hear Donald talking about how something is the greatest, the best, the biggest, the most tremendous,” writes Mary, it is essentially the voice of a boy playing to an audience of one — his father — from whom he sought approval his entire life.

As Trump faces scrutiny beyond any he has ever had to face, and societal crises beyond what most of us alive will ever faced, Mary Trump suggests that her uncle is doubling down on rigid, childlike responses.

“Donald today is much as he was at three years old: incapable of growing, learning, or evolving, unable to regulate his emotions, moderate his responses, or take in and synthesize information.”

To date, it appears nobody has ever successfully told him no. He was beyond his mother’s control from early on. When his New Jersey casinos went bankrupt, losing $1.5 billion for shareholders and bondholders, the banks let him slide with a $450,000-a-month allowance. When he was impeached, the U.S. Senate declined to remove him.

Each time he violates healthy norms with little consequence, he becomes more emboldened and grandiose, and the collateral damage mounts.

Tragically, she writes, it would have been easy for Trump to be a hero in the face of the current pandemic. But his childhood-acquired inability to acknowledge failings and downturns, for fear such admissions would tarnish his image, has led to self-destructive behavior for which we all may pay a price.

Copyright © 2020 Dan Neuharth PhD MFT

References

M. L. Trump, Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020). https://www.amazon.com/Too-Much-Never-Enough-Dangerous/dp/1982141468/