Anxiety

Bigger Than Elvis

What the story of Brian Epstein teaches us about anxiety.

Posted October 27, 2020

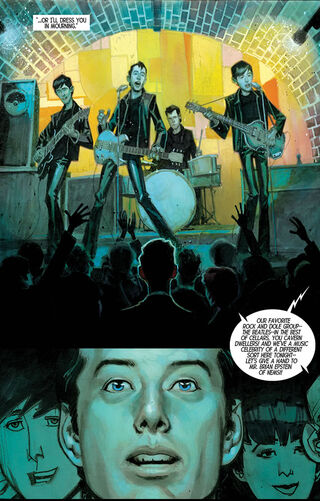

Twenty-nine-year-old Brian understood the risk and reward of worry, particularly on the most unforgettable and anxiety-filled day of his young life. He was only a bit older than the band of teenagers he had just started managing. He knew they were destined to change the world with their music, but they needed him—him—to put them on the map, and on stage so that everyone could see what he saw. He was on his way now to this first step in his grand plan—a show he booked by using every trick he knew. He even told the venue that the band would waive their fee. Everyone thought he was crazy, but he knew this would be their big break.

In the car, although perfectly coiffed and dressed as usual, he was on fire inside. He found himself gulping for air, anxiety overwhelming him. Maybe all the naysayers were right. He had been thrown out of every school he ever attended, never fit in in his hometown. If it wasn’t for his family business, he would probably be poor and struggling. A loser.

But one thing losers don’t have, he reminded himself, was a vision. From the moment he saw the band in that dingy little basement venue, he could see months, years into the future. He could see the greatness of which they were capable. His job would be to curate that greatness.

After all, Brian was Brian Epstein, the band was the Beatles, and the venue was the Ed Sullivan Show, the Beatles’ historic breakthrough introduction to the U.S. After that show, everything changed and they skyrocketed from a somewhat popular U.K. band to a worldwide sensation. They were, as Brian predicted on the day he met them, bigger than Elvis. Anxiety allowed him to think into the future—sometimes worrying, but much of the time envisioning what he hoped for, dreamed of, and desired. His anxiety fueled his drive and passion and he made his dreams into reality.

Brian’s life also illustrated the perils of that drive and passion.

Often referred to as the fifth Beatle, he engineered the Beatles’ transformation from a local band playing dingy clubs in the early 1960s, to international stars by 1964, to arguably the greatest pop music group of all time. Some rock historians even credit him with the creation of modern pop music. But in 1961, Brian Epstein was perhaps the least likely to carry this mantle. He was an army reject and drama school dropout. He loved music, but mostly classical and jazz. He struggled with anxiety and feeling the outsider in his small, working-class, seaside hometown of Liverpool.

But everything changed the night he sat in the back of a divey rock club in Liverpool called The Cavern. He was there because teenage customers had been coming into the small record store his parents let him run out of their furniture shop to buy a Tony Sheridan record, recorded in Germany, with a band called the Beatles playing backup. But the kids weren’t asking for the Tony Sheridan record. They were asking for the Beatles.

As he sat in The Cavern, very much out of place in his tailored suit, he watched a slouchy group of teenagers in leather jackets and dirty jeans take the stage, smoking and flirting with their female fans rather than performing any songs. Finally, after what seemed an eternity, they – the Beatles – actually started to play. Brian was gob-smacked. the Beatles transformed from a bunch of irreverent, immature kids into charismatic, ferocious, joyful musicians. In a flash of inspiration, Brian saw something that nobody—even the Beatles—saw. He saw that this motley crew could elevate pop music to an art form—if he could open the right doors and guide them. Vivek Tiwary, who is the author of The Fifth Beatle and studied Brian Epstein for 25 years, said: “The most important thing he gave the Beatles was his vision. In terms of the Beatles, Brian was everything.”

In three short years, Brian not only got the Beatles a record deal—after being turned down by every single British record label—but put them on the world map when they took the stage on The Ed Sullivan Show on Feb. 9, 1964. It was this show that opened the floodgates called the British Invasion, not to mention Beatlemania. Soon, other U.K. bands—the Rolling Stones, the Kinks, and The Who, to name a few—followed. Pop music was about to change forever.

As Brian had predicted, the Beatles were bigger than Elvis. His relentless hard work, devotion, and cleverness made his vision into reality. But this success didn’t alleviate the anxiety and depression he’d struggled with all his adult life. If anything, his descent into emotional struggles accelerated while he developed an addiction to prescription drugs to treat his anxiety and emotional distress, including benzodiazepines.

The truth was Brian was not just the successful elegant, perfectly coiffed and tailored man-about-town that he showed to the world. He was also Jewish, gay, and from the backwater Liverpool (instead of the center of culture, London) — although he had studiously erased all signs of these facets of himself. In the anti-Semitic U.K. of the ’60s, people who were outsiders like him didn’t run the music industry or manage musical artists. Men like Sir Joseph Lockwood, who ran the record label EMI, did. Being gay at a time when homosexuality was illegal also meant that Epstein battled loneliness and had to “hide his love away.” Vivek notes, “As a gay man in the '60s who knew he was never going to have children, the Beatles were the kids he gave his unconditional love to.” Indeed, up until 1973, psychologists and psychiatrists diagnosed homosexuality as a form of mental illness, and the source of most of Brian’s prescription drugs was his family doctor who was not only treating his anxiety and depression but trying to “cure” him of his “unnatural tendencies.”

His anxiety for the success of his band was not just for the worldly success – which he experienced in spades – but the painful anxiety of not feeling comfortable in his own skin. He medicated and dulled that pain to keep pursuing his vision, but this led him into dangerous, and eventually fatal, territory. In 1967, at the age of 32, Brian died of an accidental overdose of a prescribed drug cocktail of medications to manage his emotional pain — benzodiazepines for anxiety combined with medications for depression and bipolar disorder.

This all happened decades ago, but it shows that anxiety and what we do with is as important then as now. What would have been the possibilities of Brian’s life had he not relied on benzodiazepines to manage his anxiety, if he had believed that he could find a way to feel comfortable in his own skin? What would have happened to the Beatles, who broke up a mere three years later, having noted that Brian was the glue that had kept them together? We'll never know, but we can benefit from the lessons of his life — both the promise and perils of living with our eyes on the future.