Attention

The Memorization Process

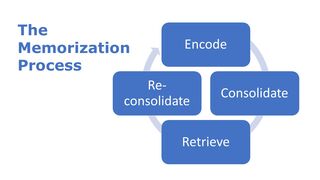

Lesson 1: Encoding, consolidation, retrieval, re-consolidation.

Posted May 28, 2020 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

As mentioned in the introduction to this free short course on learning and memory, when I was in the 7th grade, I finally became motivated to be a better student than the D-student I was in the 4th grade. (I don’t remember what my grades were in the 5th and 6th grades, but it is a good bet they weren’t impressive.) In the 7th grade, the crush I had on my gorgeous female teacher, Miss Torti, made me take stock of what I had to do to make good grades to impress her by being the top student in the class.

One of the first things I realized was that no one thing was the problem. I could study more, but that in and of itself did not seem likely to improve my memory ability. No, I did not want to work harder. I wanted to figure out how to work smarter. In those head-scratching days in the first few weeks of 7th grade, I realized that several things must be in play, and I had to figure out what they were and work on improving my ability to do those things.

First, it was rather obvious that I couldn’t memorize some piece of her instruction if it did not register in the first place. The formal word for that is “encoding,” which, of course, I did not know. But I did intuitively understand that I had to pay attention to what Miss Torti said and to those things in my books that she said were important to know. Moreover, even my 7th-grade brain figured out that I had to pay attention to get things to register. So, I started to pay attention more intensely. I made myself stop thinking about other things or daydreaming during her instruction.

I quickly learned that paying attention was a big help. But I also discovered that a day or so after a lesson, I forgot what I knew that I had paid attention to well enough to learn. Then the obvious hit me: What good is learning if I don’t remember it? To impress Miss Torti, I had to remember what she was teaching days, even weeks, after she taught it, as when quiz time rolled around.

So, despite my lack of understanding as to what was going on, I realized that I had to check myself every day or so to see if I remembered things I had just learned. If I forgot something, I had to re-learn it. Now that is aggravating. Why can’t I learn it just once?

So, one thing I figured out was that my initial paying attention was not enough. I needed to pay attention hard. What did that mean? It meant to me that I had to think hard about what I was paying attention to. What did I already know that was similar? How could this new information be important? Were there some associated cues that I could package with this information to help me remember it? How could I use this new information to learn other things?

Some of this thinking did not occur all at once. Some things occurred to me a few hours or days later. Unknown to me, there was a process going on in my brain that scientists call “memory consolidation.” This is a biochemical process that is spread out over time because the neural circuits needed to store a representation of the information have to be constructed—and that takes a while.

As I thought about things over time, it also became obvious that in order to think about the academic content, I was actually retrieving it so I could think about it. There is a process associated with retrieval in general that I did not learn about until some six decades later, when neuroscientists discovered that retrieval triggers re-consolidation. That is, when you retrieve something you have learned, the brain treats it as a well-formed “new” piece of information, well-encoded because it is already partially learned, and it can be associated with anything new at the time, such as the context at the time retrieval was triggered. Then the old and new get re-consolidated together as a new, more strongly encoded item of information. In other words, memorizing is not an event at one point in time. It is a cyclic process.

Clearly, what we can now see, though I did not understand it in the 7th grade, is that memorization is a cycle involving encoding, consolidation, retrieval, and re-consolidation. Each time the brain puts some new information through this cycle, the memory gets stronger and stronger, and more and more permanent. In the 7th grade, I stumbled into this cycle without really understanding why it worked. All I knew was that it worked.

Wow, did it work! I got all "A"s and a number-one ranking in every course, from 7th grade onward until college. Many decades later, as I learned more about this cycle, it inspired me to write the book for all students of all ages: Better Grades, Less Effort.

Summary:

- New information needs to be strongly encoded in order to be remembered.

- Memory requires nurturing and protection in the mind to allow consolidation into a more permanent memory.

- Forcing yourself to retrieve a weakly formed memory strengthens the encoding and provides the opportunity to incorporate new cues and information.

- A retrieved memory is re-consolidated, strengthening the original version.

Next Lesson: Week 2: Paying Attention