Bias

Where Do the Rules of Grammar Come From?

Researchers use constructed languages to probe how we learn grammar rules.

Posted August 8, 2019

When we speak our native language we unconsciously follow certain rules. These rules are different in different languages. For example, if I want to talk about a particular collection of oranges, in English I say

Those three big oranges

In Thai, however, I’d say

Sôm jàj sǎam-lûuk nán

This is, literally, Oranges big three those, the reverse of the English order. Both English and Thai are pretty strict about this, and if you mess up the order, speakers will say that you’re not speaking the language fluently.

The rule of course doesn’t mention particular words, like big, or nán, it applies to whole classes of words. These classes are what linguists call grammatical categories: things like Noun, Verb, Adjective and less familiar ones like Numeral (for words like three or five) and Demonstrative (the term linguists use for words like this and those). Adjectives, Numerals and Demonstratives give extra information about the noun, and linguists call these words modifiers. The rules of grammar tell us the order of these whole classes of words.

Where do these rules come from? The common-sense answer is that we learn them: as English speakers grow up, they hear the people around them saying many, many sentences, and from these they generalize the English order; Thai speakers, hearing Thai sentences, generalize the opposite order (and English-Thai bilinguals get both). That’s why, if you present an English or Thai speaker with the wrong order, they’ll immediately detect something is wrong.

But this common-sense answer raises an interesting puzzle. The rules in English, from this kind of perspective, look roughly as follows:

The normal order of words that modify nouns is:

Demonstratives precede Numerals, Adjectives and Nouns

Numerals precede Adjectives and Nouns

Adjectives precede Nouns

There are 24 possible ways of ordering the four grammatical categories. If the order in different languages is simply a result of speakers learning their languages, then we’d expect to see all 24 possibilities available in languages around the world. Everything else being equal, we’d also expect the various orders to be pretty much equally common.

However, in the 1960s, the comparative linguist, Joseph Greenberg, looked at a bunch of unrelated languages and found that this simply wasn’t true. Some orders were much more common than others, and some orders simply didn’t seem to be present in languages at all. More recent work by Matthew Dryer looking at a much larger collection of languages has confirmed Greenberg’s original finding. It turns out that the English and Thai orders are by far the most common, while other orders—such as that of Kîîtharaka, a Bantu language spoken in Kenya, in which you say something like Oranges those three big—are much rarer. Dryer, like Greenberg, found that some orders just didn’t exist at all.

This is a surprise if speakers learn the order of words from what they hear (which they surely do), and each order is just as learnable as the others. It suggests either that some historical accident has led to certain orders being more frequent in the world’s languages, or, alternatively, that the human mind somehow prefers some orders to others, so these are the ones that, over time, end up being more common.

To test this, my colleagues Jennifer Culbertson, Alexander Martin, Klaus Abels, and I are running a series of experiments. In these, we teach people an invented language, with specially designed words that are easily learnable, whether the native language of our speakers is English, Thai or Kîîtharaka. We call this language Nápíjò and we tell the people who are doing the experiments that it’s a language spoken by about 10,000 people in rural South-East Asia. This is to make Nápíjò as real as possible to people.

Though we keep the words in Nápíjò the same for all our speakers, we mess around with the order of words. When we test English speakers, we teach them a version of Nápíjò with the Adjectives, Numerals and Demonstratives after the Noun (unlike in English); we also teach Nápíjò to Thai speakers, but we use a version with all these classes of words before the noun (unlike in Thai).

The idea behind the experiments is this: We teach speakers some Nápíjò, enough so they know the order of the noun and the modifiers, but not enough so they know how the modifiers are ordered with respect to each other. Then we have them guess the order of the modifiers. Their guesses tell us about what kind of grammar rule they are learning, and the pattern of the guesses should tell us something about whether that grammar rule is coming from their native language, or from something deeper in their minds.

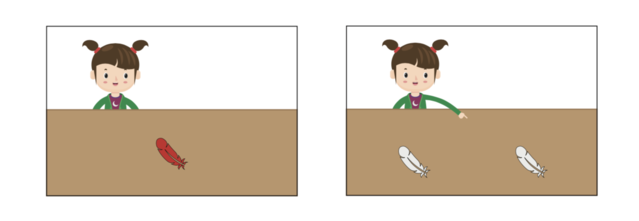

In the experiments, we show speakers pictures of various situations–for example, a girl pointing to a collection of feathers—and we give our speakers the Nápíjò phrase that corresponds to these. The Nápíjò phrases that the participants hear for the diagrams below would correspond to red feather on the left and to that feather, on the right. We give the speakers enough examples so that they learn the pattern.

Once the participants in the experiment have learned the pattern, we then test to see what they would do when you have two modifiers: for example, an Adjective and a Numeral, or a Demonstrative and an Adjective. We have of course, somewhat evilly, not given our speakers any clue as to what they should do. They have to guess!

Now, if the speakers are simply using the order of words from their native language, then they should be more likely to guess that the order of words in Nápíjò would follow it. That’s not, however, what English or Thai speakers do.

For a picture that shows a girl pointing at "those red feathers", English speakers don’t guess that the Nápíjò order is Feathers those red, which would keep the English order of modifiers but is very rare cross-linguistically when the noun comes first. Instead, they are far more likely to go for Feathers red those, which is very common cross-linguistically (it is the Thai order), but is definitely not the English order of the modifiers.

Thai speakers, similarly, didn't keep the Thai order of Adjective and Demonstrative. Instead, they were more likely to guess the English order, which, when the noun comes last (as it did for them), is very common across languages.

This suggests that the patterns of language types discovered by Greenberg, and put on an even firmer footing by Dryer, may not be the result of chance or of history. Rather the human mind may have an inherent bias towards certain word orders over others.

Our experiments are not quite finished, however. Both English and Thai speakers use patterns in their native language that are very common in languages generally. But what would happen if we tested speakers of one of the very rare patterns? Would even they still guess that Nápíjò uses an order which is more frequent in languages of the world?

To find out, we've just arrived in Kenya, where we will do a final set of experiments. We’ll test speakers of Kîîtharaka (where the order is roughly Oranges those three big). We’ll test them on a version of Nápíjò where the noun comes last, unlike in their own language. If they behave just like Thai speakers, who we also taught a version of Nápíjò where the noun comes last, we will have really strong evidence that the linguistic nature of the human mind shapes the rules we learn. Who knows though, science is, after all, a risky business!

(Many thanks to my co-researchers, Jenny Culbertson (Principal Investigator), Alexander Martin and Klaus Abels for comments, and to the UK Economic and Social Research Council for funding this research)