Parenting

Stranger Danger: Real Risks vs. Ancient Terrors

Why modern parents are not waving but drowning.

Posted June 30, 2014

Among all the persistent fears that beset parents, stranger danger is perhaps the most exaggerated. When it comes to people danger, the biggest threat to a child’s well-being is its own family–especially its parents. We all know this. But just as I know I’m safer in an aeroplane than a car, it just doesn’t feel like it.

Worldwide, traffic accidents and drowning are the top fatal risks for children (most child drownings occur in swimming pools with one or both parents present). In 2006, 2 year old Abigail Rae wandered out of her U.K. nursery and drowned in a pond. A stranger saw the toddler out alone, but didn’t want to approach her in case he was accused of child-abduction. The real crime here was negligence by the nursery–just as child neglect and maltreatment are the overwhelming, ongoing crimes against children generally. That stranger was a 37 year old bricklayer–potentially physically formidable.

A recent paper by a group of psychologists at the University of California tested the idea that parents, compared to non-parents, really do judge strange men as being more formidable. They asked parents and non-parents, male and female, to read a scene describing a walk through a wood to a car park at night. In some cases, they were told they had a child with them, and some parents had their own child with them. As they went through the woods, a strange man approached. At this cliff-hanger point–the story ends and readers were then given a range of visual clues to choose from to describe how big, tall and muscular they imagined the strange man to be as measures of how formidable they were.

Parents–both mums and dads–definitely estimated the stranger to be taller and more muscular. While both parents and non-parents showed a tendency to rate the stranger as more formidable if they had a child with them, it didn’t matter whether parents had their own child or someone else’s child with them. Overall though, the biggest difference was between parents and non-parents irrespective of having an accompanying child. Seeing a stranger as more formidable leads to more cautious, risk-averse behaviour due to a more pessimistic view of the likelihood of winning a direct confrontation.

In a follow-up study, 111 women were stopped in the street and asked to estimate the height, size and muscularity of an angry-looking man after looking at his mug shot. 61 of these women were mothers and 47 of them had their children with them (they would have liked to include fathers in this second study but they couldn’t find enough men on the street who had children with them–that’s a whole other post!). Again, mothers estimated the angry man to be more formidable–but this was unaffected by whether the child was with them or not.

The researchers were able to control for the formidability of the women themselves this time around using self-reported defence skills and hand grip strength (which didn’t differ between mothers and non-mothers). Personally, I would like to have seen a test for walking upstairs carrying a heavy (possibly squirmy) load under one arm while either carrying another load (such as a full cup of tea) in the other hand–or pushing a pointless empty stroller through a crowded shop with the squirmy load over one shoulder. I only developed these formidable skills after parenthood.

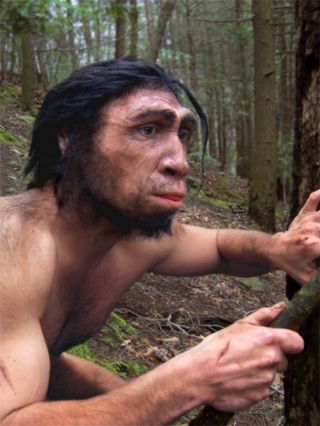

Way back in the Stone Age, we probably didn’t meet as many strangers as often as we do now and strangers, especially adult men, would sometimes have posed a real threat to vulnerable families. It would have made good sense for parents to avoid confrontation by over-estimating that risk not just on account of their kids but for themselves too because a dead or injured parent can’t protect a child.

Today, unless you live way out in the boondocks, you are likely to see at least one unknown face every day. Rare as it might be, knowing that even one of these strangers could be a serious threat to your child can prey on the mind–and hit an ancient emotional trigger that is relatively untouched by more mundane everyday risks–such as drowning.

Parents’ very different assessment of stranger danger vs the risk of drowning illustrates how our minds have adapted depending on the cost vs benefit of a risk rather than the real likelihood of disaster. There were no traffic accidents in the Stone Age but drowning must always have been a hazard. Nevertheless fish and sea food were an important part of the diet and a good source of the essential fatty acids required by the expanding human brain. Regular drownings would have been a small price to pay for surviving siblings with top quality brains. At the gaming table of evolution some risks are worth taking more than others.