Bias

If Banning Bias Doesn't Work, What Will?

Has the research discovered anything?

Posted April 29, 2019

Diversity programs aimed at outlawing bias and prejudice are doomed to fail.

A review of the professional and scholarly literature on diversity training programs shows that after 50 years and thousands of workplace diversity intervention programs the most accurate answer to the question if they are effective at outlawing bias? The answer is “No.”

Most diversity training programs in the workplace are designed to ‘encourage’ people to value and appreciate diversity. They have an agenda to promote.

But studies suggest that trying to command people to adopt beliefs and behaviors can actually trigger oppositional behaviors. Most people will resist being told what to think and how to behave.

The scholarly literature on bias and prejudice is among the most remarkable in all of the social sciences.

The total volume of scholarship is notable reflecting decades of scholarly study of the etiology, definition, measurement, and the consequences of bias and prejudice. It has attracted a range of theoretical views and debates about the best way to measure and conceptualize bias and prejudice. The result is a variety of assessment tools to measure bias and prejudice.

Less remarkable is the status of this literature when evaluated for the practical knowledge and solutions produced.

Studying bias and prejudice attracts attention because scholars want to understand, and remedy social problems linked to bias and prejudice like violence, inequality, and discrimination. Policymakers share their goals and spend billions of dollars yearly on interventions aimed at prejudice reduction in businesses, schools, neighborhoods, and regions troubled by intergroup conflict.

So, given these practical goals, it is natural to ask if anything has been discovered about the most effective ways to reduce bias and prejudice?

Of the hundreds of scholarly studies reviewed by academics, the findings reveal that bias and prejudice reduction interventions in businesses, schools, neighborhoods, and regions troubled by intergroup conflict are ineffective or at best the effects are limited or unknown. Scholars have reached the sobering conclusion that more studies need to be done to determine what if anything works.

It should not be surprising that bias and prejudice cannot be outlawed or commanded away when we consider the biological evidence.

The control and command type diversity training programs and interventions ignore everything scientists know about our biological preferences for people who are like “us,” our need to belong, and maintain our identities.

A cornerstone of the literature and one of the best-replicated findings in science is the “cross-race effect” also known as the “own-race-bias effect.” These terms mean that people are more accurate at recognizing faces from their own racial, ethnic group than faces from other racial, ethnic groups. This own-race-bias effect makes it difficult for people of one race to easily recognize or identify individuals of another. That so-called racially biased expression, they all look similar to me, is scientifically correct. Studies have shown that this behavior is not just social; it’s hard-wired into our brains. (Distinguishing between two people of a race different from your own is not impossible, but it requires mental effort even for those who are mindful of their limitations).

In addition, studies have demonstrated that our bias for own-race faces starts in the first few days of life. Newborn infants demonstrate a visual bias for their mother’s face over a stranger’s face and at 3 months old, infants show a bias for faces from their own-ethnic groups. As children develop, they also develop emotional attachments and a need to belong to their ethnic groups. Research on the development of the self in relation to others shows that the need for attachment and belonging continues throughout the life cycle.

Besides our own race biases, our attachment needs, and our need to belong, we also have memories and histories some of which contain stories about traumatic injustices that have been transmitted down generations.

Darwin argued that people have an innate sense of what “ought” to be, an idea that gestalt psychologists expanded on. They argued that the sense of ought is similar to our visual (perceptual) organization. People have an innate cognitive and perceptual tendency to find balance, wholeness, and consistency. An injustice leaves people feeling that something is out of balance, incomplete, and inconsistent. Bringing about needed closure is tantamount to justice and balance.

However, a conundrum arises in instances when the human drive for fairness and justice cannot be rebalanced. For instance, neither the law nor individual attempts to restore justice could successfully redress the traumatic injustices of slavery and the Holocaust. In fact, research shows a neural foundation for the need for revenge and retribution. Injustice becomes an intergenerational matter when injustices are not rebalanced between people; after the original people involved die, they simply extend to their descendants.

Evidence for this phenomenon was evident in a groundbreaking study I conducted that brought children of Holocaust survivors face-to-face with children of Nazis; later, another study of great-grandchildren of African American slaves with descendants of slave owners. The children of both survivors and of Nazis and great-grandchildren of African American slaves and slave owners reported that they felt they had inherited a dark legacy that consumed large parts of their lives and identities.

In sum, in order to comprehend the complexities of our biases, it is necessary to understand the biological, neurological and psychological make-up of people. Commanding people to get rid of their biases, memories, and histories is akin to asking them to shed their very identities. Then, reason and rationality can take us only so far when addressing biases, attachment, and belongingness needs.

If biases cannot be outlawed by facts and rationality is there anything we can do? Are there any solutions we can live with?

The quick answer is yes. The solution requires a fair process of facilitated discussions using the scientific method.

My students and I have been studying this process foralmost thirty years.

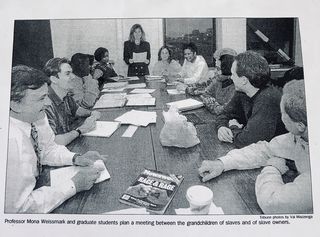

We organized the first research study on descendants of slaves and descendants of slave owners. Twenty people — half of them descendants of slaves, the rest descendants of slave owners — met around a seminar table at a university in Chicago for four-days of facilitated discussions. They all had to agree to be closeted for six hours a day in a seminar room for intense facilitated discussions of slavery, guilt, resentment, injustice, forgiveness, and reconciliation.

Melita Garza a journalist at the time with the Chicago Tribune reported on the meeting and published a cover story in the Chicago Tribune Tempo Section (June 2, 1995) titled ‘Lancing the Past.’

The photo accompanying the story showed the participants sitting in a circle with the caption

“descendants of slave and slave owners meet in a conference room … as a way of finding common ground.”

Source: Tribune Photos by Val Mazin

Another photo showed a black woman, a descendant of slaves, hugging a white woman, a descendant of slave owners after the four–day session.

Source: Tribune Photos by Mike Fisher

Also, the UK journalist Veronique Mistiaen reported on the meeting and published a story in She Magazine (October, 1995) titled Slaves to the Past and the photos also showed the participants hugging and embracing each other.

Mistiaen concluded her story this way:

"If the descendants of victims and victimizers were able to leave most of their anger, fear, and mistrust behind and take back to their lives understanding and compassion, perhaps other polarized groups elsewhere in the world could attempt the same?"

What happened during those four days making it possible for the participants to leave behind their feelings about the “other”?

The joint facilitated discussions depolarized the groups and helped redress injustices. The participants had learned the history behind their feelings and those insights changed the way they saw each other: not by blaming and shaming and not by outlawing bias, or mandatory politically correct slogans rather by facilitated discussions using the dialectic method.

The dialectical method is the method used in science and problem-solving education. It is a dialectic between people holding different points of view and deeply felt emotions about a subject but wishing to understand the other and test their views.

Throughout the world and over the arc of time, hatred and resentment have been passed from generation to generation; for most of us, our desire for justice is deeply shaped by our emotions. Forgiveness and a sense of reconciliation with those who we feel have harmed us, our families, and our communities can be difficult to achieve.

It is, however, possible.

Several months before her death, someone from the Shoah Foundation asked my mother, “What would you like to tell the world about the pain you suffered in Auschwitz?” My mother paused for a moment and then said: “I want the world to know that no one ever again should suffer as I did.”

My mother was a meliorist; she thought it was possible people could improve.

The research supports my mother’s faith that people can, through their interference with processes that would otherwise be natural, produce an outcome that is an improvement. Science reveals that a fair and facilitated process over a control and command approach can improve the relationships between polarized groups. We cannot outlaw our biases, but we can learn to understand our biases and how they influence our interactions with others.

Copyright © Mona Sue Weissmark All Rights Reserved

References

Weissmark, M. (forthcoming 2019). The Science of Diversity. Oxford University Press, USA.

Weissmark, M. (2004). Justice Matters: Legacies of the Holocaust and World War II. Oxford University Press, USA.

Weissmark, M. & Giacomo, D. (1998). Doing Psychotherapy Effectively. University of Chicago Press, USA.