Eating Disorders

Recovering from Anorexia: How and Why to Start

How to help your understanding of your illness lead to active recovery

Posted January 19, 2015 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Getting Stuck Halfway

"What strikes me most about what you write is that you can be so coherent about it all, and understand yourself so much, and still do not just throw up your hands and laugh and say – 'to hell with that,' and just eat what you feel like. I am sure you see this equally clearly and that doesn’t bring the spontaneous laugh bubbling up from wherever they come from." (11 March 2003)

Thus my mother wrote to my 21-year-old self. Probably anorexia’s most frustrating feature for the person looking on, willing the sufferer to get better, and not understanding why he or she doesn’t, is the baffling chasm between insight and action. Anorexia is perhaps unusual amongst mental illnesses in that the coexistence of a profound understanding of the ways in which the disorder is negatively affecting one’s life and health with a complete inability to act on that understanding by embarking on recovery isn’t just an anomalous feature of the illness in a minority of sufferers some of the time, but seems to be one of its core traits.

There’s usually an earlier phase of illness in which the sufferer denies that anything is wrong, but once denial comes to an end and is replaced by acceptance of the fact of being ill, there is all too often a striking failure to then make the next transition: to eating more and starting to get better. This state of failing to act may last years or even decades. This, if anything, is what the uncomfortable experience of anorexia is: a cognitively dissonant state of knowing you’re harming yourself but not feeling able to do anything about it. (In this respect, it bears significant similarities to substance abuse and addiction, but I’ll consider this and other resemblances in more detail in a future post.)

My blog post on how and why not to get stuck in the limbo between illness and recovery has generated more comments from readers than any of my other posts. Getting stuck halfway through recovery is a specific manifestation of the general case: the failure to translate understanding illness into recovering from it. In anorexia, the prototypical example of this broad phenomenon is arguably not managing to start recovery at all: that all-too-familiar state of paralysis between acceptance (possibly in conjunction with formal medical diagnosis) and a first attempt at recovery.

I spent years there, trapped in what I described in that email exchange with my mother as "the gulf between reasonably clear rational insight and the inability to translate it into change, to dictate to the deeper mechanisms; between knowledge of powerlessness and the illusion of control" (11 March 2003). And that’s the trap I’ll discuss here, first attempting to explain its entrapping qualities, and then suggesting some possible ways out – or rather, since you probably know perfectly well already what the ways out are (yes, they involve food, and lots of it), some ways of giving yourself the courage to take them.

The Feedback Loops of Starvation

What distinguishes anorexia most clearly from other eating disorders is that the interactions between physical and psychological factors which create and sustain it include the profound effects of starvation, on both the body and the mind.

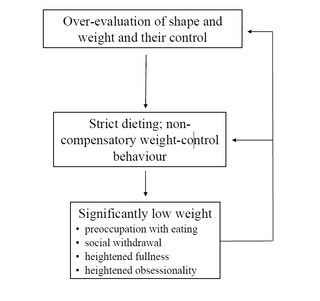

The physiological factors caused by starvation make the feedback loops that act to maintain all eating disorders even more pernicious in anorexia. As this diagram from Christopher Fairburn’s 2008 clinical manual Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Eating Disorders illustrates, weight loss itself exacerbates the vicious circle of a restrictive eating disorder through its combined physical and psychological impact. It doesn't matter where the cycle starts — it might begin with weight loss or weight control for some unrelated and apparently innocuous reason. Wherever it starts, each element contributes to the next in a perfect vicious spiral: the effects of underweight driving the preoccupation with body size driving the undereating which drives the weight down further...

This potent feedback loop contributes to the feeling in anorexia that everything is closing in on itself, until nothing else seems even conceivable, let alone desirable. Thought becomes as rigid and circular as action, so that even thinking about change becomes difficult, and making it happen becomes a distant undreamt dream.

In this context, it’s crucial to understand that starvation damages the brain just as it does the rest of the body: the researchers involved in the Minnesota starvation study (Keys et al. 1950, The Biology of Human Starvation) found consistent evidence of brain tissue loss between 4 and 10% in famine victims (a finding substantiated by more recent brain-imaging studies, e.g. Kato et al., 1997; Roser et al., 1999). This happens because the brain’s lipid content gets used as fuel during starvation. The significant changes to neural as well as endocrine and metabolic functioning have correspondingly profound effects not just on the physical state of people with anorexia, but also on mood and thought patterns.

As the Minnesota study showed so clearly, starvation not only makes people deeply preoccupied with food, it also makes them depressed, self-centered, and irritable. These effects make it easier for the sufferer to retreat into illness and into isolation, so that even though they are part of the problem, the psychological effects of starvation are also part of what prevents full recognition of the problem. Depression, for example, reduces motivation to act to improve a negative situation, partly because it also reduces the ability to respond positively to positive situations (e.g. Austin et al., 2001). If you don’t even experience positive changes as rewarding, the difference between a bad situation and a better one becomes clouded, and so entrapment in illness can easily take hold.

The same circularity results from the effects of starvation directly on patterns of thought, which in a starved mind often become more rigid, more characterized by black-and-white, all-or-nothing polarities. Geoffrey Wolff and Lucy Serpell’s cognitive model of anorexia (in Hoek et al., 1998, Neurobiology in the Treatment of Eating Disorders, p. 412) illustrates how a dysfunctional set of cognitive schemas can result in an unstable oscillation between opposite extremes: "If I’m not special, I’m worthless," "If I’m not an angel, I’m bad," "If I’m not in control, I’m powerless." These impossible extremes present themselves as the only possible options. And as the illness progresses, they become increasingly intertwined with value judgments relating to eating and the body: "If I’m thin, I’m special; if I’m fat, I’m worthless;" "If I can’t control my weight, I’m powerless;" "If I’m not a bag of bones, I’m fat."

Structures like these, because they strip away the space between the ideal and the deplorable, preclude calm reflection on what the real, manageable problems are and how they might be practically addressed. Similarly, the cognitive rigidity brought about by starvation can manifest itself in an inability to grasp the big picture and instead get stuck in the details; I’ve talked about this before in an academic context, and this phenomenon too acts powerfully against the achievement of a realistic overview of how anorexia is affecting one’s life, which is necessary if change is to happen.

In her excellent 2011 book Anorexia Nervosa: Hope for Recovery, Agnes Ayton offers a nice summary of these cognitive-psychological effects and the effects they in turn have on the sufferer’s motivation to seek help or embark on recovery:

Starved patients usually develop a set of characteristic changes indicating impaired brain functions. These include depression and irritability initially. Later on, rigid thinking appears, and after that, apathy, and concentration and memory problems can develop. People often recognise that they feel unwell, but do not know why. Seriously starved patients can have trouble retaining and processing information. If this is the case, they are usually unable to make treatment decisions for themselves. (p. 157)

Later she puts this even more starkly: "By the time people with anorexia become seriously unwell, they have often lost touch with reality. This is because of the effects of severe starvation on the brain" (p. 176). Ayton points out that this logic of self-disguising effects extends to the squarely physical symptoms of anorexia too: the loss of muscle mass brought about by undereating, for instance, contributes to a lower total body mass, which often results in a feeling of lightness and energy when exercising (cycling uphill, say), something that is lost when weight gain in recovery begins, even though in reality the body is now getting stronger again. In multiple respects, then, but in none more profoundly than the cognitive, anorexia activates mechanisms that work against both recognition and curative action.

Anorexia’s Appeal

It’s nonetheless important to acknowledge that anorexia is so resistant to all resistance against it because it also offers some positives; if it didn’t, after all, it would be far easier to tackle. Ayton (2011, p. 140) notes some evidence that being underweight can offer some relief from conditions such as hayfever, eczema, and acne. More centrally and immediately, feeling hunger and not responding to it by eating creates a short-term high: for many people, at least some of the time (especially in the early days), hunger brings a hormone-driven euphoric mood.

Via a similar mechanism to the endorphin production that follows self-harm, this can offer short-term relief from anxieties that might otherwise be crippling, whereas any attempt to do otherwise and eat more inevitably brings a short-term intensification of such anxieties. Excessive exercise does something similar: It heightens mood and also reduces appetite, if only temporarily. The trouble, of course, is that the more these responses are practiced, the more doing otherwise becomes distressing: avoidance strategies ultimately only strengthen whatever is being avoided. (Hence my argument for weighing oneself in recovery rather than avoiding it.)

In anorexia, though, avoidance is at the heart of everything, just dressed up as something more admirable. Anorexia’s trump card is the emptiness it calls "control" (see my two posts on control here and here). No matter that the control exerted in anorexia is a hollow imitation of any positive version of control; no matter that it gives the anorexic nothing more tangible than a fleeting hunger-centered buzz followed by a long trough of bleakness; no matter even that (except perhaps in the very first honeymoon period of illness) control, to the extent that it ever existed at all, is replaced by its opposite, the abject state of being controlled by the thing that was meant to solve your problems but turns out to be the greatest problem of all. Somehow the control mantra survives, disconnected as it is from any discernable benefit, no more than an incessant whisper of something that once upon a time maybe had meaning.

It’s also true that in many cases, at least until starvation has reached its most severe phase and obsessive-compulsive or suicidal urges strip away the last shreds of any illusion of control, anorexia (of the restrictive rather than the binge-purge variety) offers greater stability than other eating disorders. There’s typically no distressing oscillation between restricting, bingeing, and purging; for the most part there’s just survival within the ever narrower bounds of what the sufferer declares acceptable. Indeed, stability to the point of stasis is often one of anorexia’s defining qualities. Life becomes an unchanging and isolated routine of work, exercise, inadequate meals, and hunger. In a world that seems ever more overwhelming in its instabilities and its complexities, the simplicity of such a restricted way of life can offer comfort of a kind, even if all anorexia’s obsessive rituals are really the exhausting opposite of simplicity.

Obviously, anorexia also makes you thin. Society seems generally to think this is a good thing. So in the early stages of illness, responses from other people tends to be encouraging — and when those responses turn to concern, and then cease altogether, it no longer matters, because thinness and control and all the things they stand for, or pretend to, have become ends in themselves. Even once you’ve recognised the damage you’re doing to your body, your mind, and your life by being pathologically underweight, the fact that recovery involves rejecting one of the most universally sought-after trappings of physical desirability makes it significantly harder even than it would be anyway.

The sufferer may well come to understand that being unhealthily thin doesn’t offer the benefits he or she may have thought it would: happiness, say; or attractiveness; or even, when body dysmorphia is involved, the self-perception of actually being thin. But in many cases, embarking on action whose aim is to put on weight, including to replenish body fat, can seem an impossibly difficult rebellion against social norms.

Anorexic weight loss (or the prevention of normal growth in children and adolescents) may also, depending on context, be attractive in other ways. It may minimize the complications associated with sex appeal (especially where this is associated with abuse-related trauma); it may be a means of attracting attention (for example from parents who are in the process of separating); and it may simply offer a way of expressing things that can’t be said any other way — as an exercise of a crude kind of control over how others perceive you. Often this takes the form of a call for help that doesn’t need words: a severely underweight body says, louder than most other languages could, "I am struggling; I am suffering." The sufferer may fear that this struggle couldn’t be expressed or detected by others if his or her weight were normal. Of course, increasingly, the struggle and the suffering are caused by anorexia itself, which also ultimately exacerbates any pre-existing problems, but in the depths of malnutrition this is often hard to understand, even harder to accept, and triply hard to act on the acceptance of.

But as the average body weight in industrialized societies increases, thinness says something else too. More and more it can be seen as exuding an aura of specialness, of superiority: the thin person can endure hunger and ignore it as other people can’t. But as I’ve already argued in the companion post to this one, the sense that thinness equals specialness is illusory and becomes directly dangerous when, in anorexia, it stops you accepting that the rules of illness and recovery apply to you as to everyone else. This doesn’t stop it from being addictive, of course, but once you look closer at what the specialness or the superiority consists in, it crumbles.

The source of it is something like this: most people struggle to control their weight, struggle not to eat too much, but I don’t, I have this completely under control, and that makes me special, and it makes other people think I’m special too. In fact, of course, being in thrall to the ideal of extreme thinness doesn’t make you special at all, however completely you end up embodying the ideal; it just makes you the victim of a dubious and transitory social valuation of something with few inherent benefits. The hollowness of the specialness anorexia provides becomes blindingly clear when recovery begins, and the sufferer struggles to cope with acting against all the pressures to eat less, to worry about gaining weight, to be thinner and smaller and less of a threat to the norm. The distress this kind of challenge causes is the clearest sign that being genuinely special, by rejecting a misguided and harmful social value system, is in anorexia not even bearable, let alone desired.

Anorexia and Other People

The positive social valuation of anorexia’s most visible symptom, thinness, contributes to one of its dangerous psychological effects: isolation. Anorexia typically makes sufferers reclusive, secretive, impatient, and routine-bound, all of which drastically reduces the likelihood of maintaining or forming meaningful relationships. Then you add to this the conflicted feelings of envy or competitiveness that often, at least in the earlier stages, form part of other people’s responses to the person with anorexia. And then you add in the ignorance and taboo that still surround mental illness and make open conversation difficult on both sides, even when it is clear there’s a serious problem.

For all these reasons, isolation becomes a major risk factor in the development and maintenance of the illness. Sufferers can easily take others’ failure to intervene to mean there’s nothing wrong: If no one says anything, then presumably I’m not eating too little, I don’t look too thin. As Ayton puts it, in responses to anorexia "there are two main types of communication problem: not saying enough, or saying too much and too harshly" (p. 116). People tend to be more frightened of the latter, because they worry about making things worse, but their silence is just as dangerous, quite possibly more so, because to the sufferer it often signals tacit acceptance or approval of the behaviors and/or the consequences of anorexia.

Sometimes silence on the part of friends and family comes not just from ignorance or fear but also from a more or less philosophical conviction that the value of individual freedom and choice is great enough that it should be respected regardless of the damage it does. Again, Ayton speaks pointedly to this:

It is paradoxical that the amount of weight loss that would create an international outrage at a population level (in Africa, for example) is often regarded as a personal choice on an individual level (and therefore not to be interfered with) by the well-meaning public and some professionals in the West. This is particularly incongruent when young people are affected by anorexia nervosa and suffer irreversible consequences. (2011, p. 143)

As should be clear from my discussion of the cognitive effects of malnutrition above, people with anorexia are often not cognitively competent to fully assess the risks of their behaviors, and it’s breathtakingly irresponsible to talk about anorexia in terms of personal choice, as pro-anorexic websites tend to.

On this note, I was appalled recently to come across an academic article in which a therapist and clinical psychologist Olga Sutherland (and Ph.D. student Andrea LaMarre) promote a relativist postmodernist perspective which regards mental illnesses as inappropriately "pathologized" by biomedical discourse, when in fact they should be recognized as admirable strategies for constructing subjectivity "in ways that contest these dominant cultural constructions and assert that the eating disorder provides, for example, comfort or empowerment rather than distress" (2014, p. 3).

The upshot of their approach is resistance to a repressive "'recovery" model, [which suggests] that illness, mental illness, and bodily difference are things to be fixed in order to maintain social order' (ibid.). Assertions of this kind make the fatal error of taking sufferers’ interpretations of their condition at face value, totally ignoring all the complex physiological and psychological damage eating disorders bring about, and offering a dangerous validation of the tendency towards social acceptance of anorexia as a legitimate lifestyle choice that shouldn’t be interfered with. This in turn all feeds into the ambivalence that prevents sufferers from moving from acknowledgment and acceptance to action towards recovery.

Discussions of this kind, which fling about references to Bordo and Foucault in a vacuum of any serious consideration of the embodied realities of eating disorders, also legitimize another facet of the trap sufferers so often find themselves caught in: the treatment of intellectual understanding of anorexia as enough in itself, as all that needs to be achieved, as almost a surrogate for recovery itself.

For me this was very much the case: both on my own and in conversation with my mother, I devoted long hours to picking apart the pseudo-logic of anorexia, to uncovering hidden paths of obsessive reasoning, to despairing and marveling at the absurdities I exposed. I even spent a whole summer writing and analyzing everything that had happened in the first six years of my illness.

But for years and years, none of that conceptual grasp of my illness led me any closer to getting better, and I think when I finally got there it didn’t have much to do with the subtleties of the conceptual grasp anyway — it was basically about being sick of living in the dark and in constant hunger and bleakness and obsessive-compulsive torture. When I unpicked anorexia’s many tantalizing paradoxes, I thought I was making progress, but because I was treating understanding as a substitute for action, I was doing the opposite.

How to Get Out

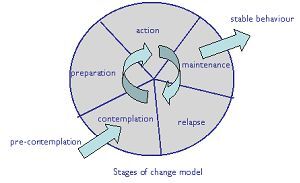

What, then, to do about all this? One popular way of understanding change in all sorts of bio-psycho-social contexts is James Prochaska and Carlo DiClemente’s stages of change model, which was developed as part of research on giving up smoking (e.g. Prochaska et al., 1994). Their cyclical model, illustrated here, differentiates between pre-contemplation, contemplation, determination or preparation, action, maintenance, and then either a breaking of the cycle through stable behavior, or relapse leading back to pre-contemplation.

The defining characteristic of the contemplation phase, in which the problem is acknowledged and change is contemplated but not yet committed to, is ambivalence. In this stage, which can last a long time, very small things can make a difference, can shift the delicate balance slightly away from the status quo. In the evolution of any successful recovery process, many forces act in many different directions, and the difference between failure and success may be only a minute imbalance in favor of either stasis or change.

So what kinds of things in particular may help shift paralysis in the form of ambivalence into tentative or determined movement?

Well, first of all, I hope (with a touch of irony) that insight into all of the above might help. Of course, the whole point of the post is that insight alone can’t bring about change, but some level of insight is necessary if not sufficient. And insight specifically into the reasons for the common time lag between insight and action might just be one of the factors that breaks effectively into the stasis.

Then there are the obvious, sensible, and irreplaceable practical steps that recovery always requires:

Composing (mentally or on screen/paper) a list of reasons not to stay ill and/or to get better.

Informing yourself about the likely difficulties of weight gain and recovery in advance (like the physical side-effects of regaining weight described here), and not expecting immediate miracles.

Constructing a concrete and feasible plan for how to eat more. (As a rough guide, adding 500 kcal a day to whatever keeps your current weight stable, and keeping eating that every day with complete consistency, is a good way to start.)

Being prepared for things to get difficult, in all the universally predictable ways (feeling nauseous around mealtimes, feeling more unstable in mood, etc.) and perhaps in some specific to you (struggling with a particular person or situation, say), and having at least a basic plan in place for how you’re going to cope (some way of keeping eating divorced from the ups and downs of the rest of life has to be at the core of this).

Not being scared to ask other people you trust for their support, whether in practical ways like buying food for or with you (as one deeply kind friend, Edmund, did for me), or simply being with you when you don’t want to be alone.

I’ll conclude with a few more specific suggestions. Ayton proposes a thought experiment:

It can help to focus your mind on recovery if you imagine that, by some miracle, the anorexia disappeared from your life. Imagine waking up one morning and not worrying about weight and shape, or food and eating. How would your life be different in that future? What would you be doing then? How can you achieve more of what you would like in your dreams? Are there any signs of this happening already? Most people want to achieve happiness. Has restricting your diet made you happy? What has been the impact of the illness on your life? And on your family? Write down for yourself how life would be if a miracle happened, and look back at it from time to time when things get tough, to remind yourself of why you want to change. (2011, p. 173)

Fairburn offers an encouraging analogy for when there seems to be too much wrong to know where or how to begin:

Fortunately, one does not need to tackle everything (for otherwise treatment would take years!). An analogy is useful here. The psychopathology of eating disorders may be likened to a house of cards. If one wants to bring down the house, the key structural card needs to be identified and removed, and then the house will fall down. So it is with eating disorder psychopathology. The therapist [or the patient] does not need to address every clinical feature. Many [problems] are at the second or third tier of the “house” and so will resolve of their own accord if the key clinical features are addressed. Examples include the preoccupation with thoughts about food, eating, shape and weight; compensatory vomiting and laxative misuse; calorie-counting; and, in many cases, over-exercising. (2008, p. 47)

This text is directed at clinicians, but for the sufferer in the contemplation phase, what it essentially means is: take heart; for now, you don’t need to worry about anything more than eating more and letting your body heal itself.

A thought for friends, lovers, relatives: gently pointing out the obvious to someone who is destroying their life through anorexia can, just sometimes, be the straw that breaks the back of this paralysis that keeps them ill. So can investigating treatment options and presenting them to the person you care about, to save them having to take that frightening step themselves. One truly generous friend called Phoebe did this for me, and by so doing she may have saved my life. Certainly I don't know when, if ever, my life would have become worth living again, had it not been for her.

And a thought about one of the many paradoxes involved in anorexia and recovery: consider taking action to engineer spontaneity. While I was ill I had many talks about spontaneity with my former English teacher and later friend, Roland. I resisted his notion that spontaneity could be orchestrated, but ultimately, as I got better, I came to understand what it means to cultivate an openness to what the world might offer, instead of binding oneself tightly in the straitjacket of the infinitely planned. Spontaneous maybe isn’t the best word for this gentler, opener attitude: perhaps instinctive, or impulsive. In any case, letting something of this kind back into life by making space for the unexpected — whether in the form of saying yes to a simple teatime out with other people, or asking a friend to organize a little adventure for you both, or taking a trip to the bookshop to ask one of the staff for a recommendation and trying whatever they suggest — may just help remind you that, even in very little ways, life really can be otherwise.

The key is to break out of the paralysis somehow, anyhow. Practicing acting – not acting as pretending, but acting as taking action — in almost any of the ways that have got rusty with disuse can help weaken the hold of the cognitive-behavioural-physical patterns of stasis that might otherwise keep you trapped forever. Whether you think you can better manage a spirit of recklessness like the one my mother dreamt of for me, or you’d rather turn your iron will to undereating on its head, and eat more just as implacably as you used to eat less, what matters is that you do something.

And I’ll end with two last images.

One comes from the interminable autobiography of an illness I wrote back in 2004. There I noted in passing that the control exercised in anorexia is "an iron grip on thin air." That image has stayed with me.

The other one takes us back to the beginning. It comes from my mother, in the email I quoted earlier. She told me that she wished the paradoxical but sterile lucidity of my latest effort of self-elucidation could just, somehow, "lead to the ridiculing laughter, the liberating laughter, of the person who says it’s all rubbish and remembers how to eat what they feel like again." Recovery frees you to laugh again with deep rich abandonment, but long before that, irreverent laughter itself can free you to start to recover.