Coronavirus Disease 2019

HIV and AIDS: Tracking a Sexually Transmitted Virus

How evolutionary biology uncovered the trajectory of a deadly disease.

Posted December 1, 2020

AIDS was a mystery disease when first formally recognized in patients in the U.S. in 1981. Transmission through sexual contact was rapidly recognized, but the source was initially unknown. Just three years later, inspired work by disease detectives (epidemiologists) identified the cause, later officially dubbed Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). No vaccine or effective cure exists, and with untreated infections, the average survival is only 11 years.

Transmission of HIV

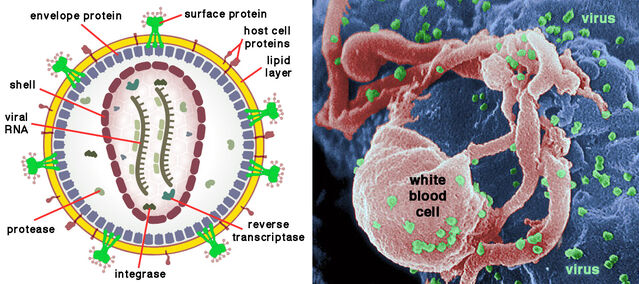

HIV belongs to the retroviruses, remarkably simple organisms with two tiny RNA molecules inside a spherical envelope that somehow escapes destruction by the host’s immune system. Each RNA strand contains just nine genes. Any retrovirus—hence the name—has the special feature that, after invading a cell, a DNA replica of its genetic material is spliced into the host’s genome. Once inserted, the viral genes exploit the cell’s machinery to produce hordes of new viral particles.

Among adults, HIV is transmitted mainly by unprotected sex but also by unsterile hypodermic needles and transfusions of contaminated blood. Mother-child transmission can occur during pregnancy, birth, or breastfeeding. Rather belatedly, it was recognized that HIV could pass from infected infants to breastfeeding mothers or female caretakers. According to a 2012 review by Kristen Little and colleagues, approximately half of women breastfeeding infected infants contract the disease.

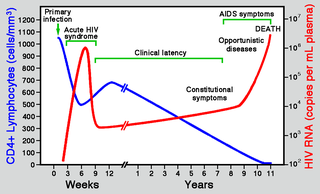

Few symptoms are apparent at first infection, although a brief flu-like illness may ensue. A lengthy symptom-free stage typically follows, but the developing disease increasingly disrupts the immune system, opening the way for familiar infections (e.g., tuberculosis) and certain cancers (notably Kaposi’s sarcoma) that rarely occur with normally functioning immunity. During this final stage, weight loss is also common. The name Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) refers to this suite of symptoms. As a rule, in the absence of antiviral therapies, HIV infection takes about a decade to become full-blown AIDS.

Tracing HIV origins

It is rarely appreciated that investigation of HIV directly benefitted from already available computer programs for generating pedigrees from DNA sequences. Beginning in the 1960s, evolutionary biologists had developed and fine-tuned these crucial tools to explore relationships in the Tree of Life. Tried and tested procedures were thus at hand for swift redeployment to reveal HIV’s origins. As the virus proliferates within and between patients, it rapidly accumulates mutations, especially in regions of the envelope gene targetted by the host’s immune system. Analyses of those changes unveil its history.

HIV falls among the lentiviruses, which typically cause diseases with an extended incubation in many mammal species. All lentiviruses provoke long-term infections, but the outcome ranges between the complete absence of symptoms and the development of fatal immunodeficiency. From the outset, it seemed likely that HIV arose through cross-infection from another mammal.

However, in one of its first important findings, tree-building soon revealed two different types of HIV, now regarded as separate species. The first (particularly infective and virulent) type discovered, labeled HIV-1, is the predominant cause of AIDS worldwide. But further research identified a less virulent and less easily transmitted second type, dubbed HIV-2, confined to West Africa.

In 1994, Andrew Leigh Brown and Edward Holmes published a landmark review of the evolution of HIV. As it happens, Eddie Holmes began his university training as one of my Anthropology students at University College London (1983-1986). Years later, he told me that my lectures on primate evolution had inspired his research interest. His stellar career in the scientific study of viruses causing major human diseases—from hepatitis through HIV to COVID-19—corroborated my long-standing conviction that a clear understanding of human health demands familiarity with evolutionary biology.

Leigh Brown and Holmes analyzed several HIV-like viruses found in various African monkeys and apes—Simian Immunodeficiency Viruses (SIVs)—and examined their relationships using tree-building. It emerged that HIV-1 originated from a virus passed from common chimpanzees to human populations in equatorial West Africa, whereas HIV-2 groups with SIVs in African monkeys, being closest to one in sooty mangabeys.

Subsequently, in a 2010 review, Paul Sharp and Beatrice Hahn discussed updated evidence relating to the evolution of HIV-1. They confirmed that the closest relatives of HIV-1 are SIVs infecting the wild populations of chimpanzees and gorillas in West Africa. Analyses confirmed that the initial hosts were chimpanzees.

In fact, four lineages of HIV-1 evidently arose in chimpanzees. At least two were transmitted directly to humans, while one or two may have been transmitted indirectly via gorillas. Sharp and Hahn found that, as with human HIV, SIV infection in wild chimpanzees increases mortality by depleting particular helper cells (CD4+ T-cells) that trigger responses to infections.

The history of human AIDS

Although it is now well established that the AIDS pandemic originally began in Africa, the date long remained uncertain. To gain insight into underlying factors, inferring a reliable date for the source is very important. Because AIDS was first diagnosed in the U.S., the location and timing of the initial infection there has also been much discussed. An airline steward who died in 1984 ("Patient Zero") was named and unfairly decried as the likely source, notably by Randy Shilts in his 1987 book And the Band Played On.

A 2016 paper by Michael Worobey and colleagues eventually reconstructed the early history of HIV/AIDS in North America. They noted that identification of a particular strain of HIV-1—group M subtype B—was a crucial advance. Previous research had indicated that subtype B circulated undetected in the U.S. during the 1970s and even earlier in the Caribbean.

Using a method developed to recover viral RNA from degraded samples, Worobey and colleagues screened over 2,000 archived serum specimens from the 1970s. They managed to obtain eight complete HIV-1 sequences from 1978-1979. Analyses revealed that a pre-existing Caribbean epidemic was the likely original source, with the U.S. epidemic most probably beginning with an ancestral HIV in New York. Worobey and colleagues also sequenced the HIV-1 genome of "Patient Zero," finding that he was neither the source of subtype B nor even the primary case in the U.S.

In a very recent paper published in 2020, Sophie Gryseels and colleagues (including Worobey) reported findings from an almost complete HIV-1 genome dating back to 1966, the oldest so far recovered. They conducted an extensive search of 1,645 tissue samples collected in Central Africa in 1958-1966 for pathological study. Their needle-in-a-haystack search paid off. One sample, from Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), was HIV-1 positive and could be allocated to a sister lineage to subtype C in group M. Overall analyses indicated that the pandemic lineage of HIV-1 originated at some time around 1900.

Tracing the origins of HIV from non-human primates in Africa has also clarified another issue. Edward Hooper, in his much-publicized 1999 book The River, claimed that the AIDS epidemic was incidentally triggered by an oral polio vaccine administered to hundreds of thousands of Africans in 1957-1960. He stated that the region concerned—DRC, Burundi, and Rwanda—was the source of the group M strain of HIV-1 virus. He further claimed that the polio vaccine was developed in the DRC using chimpanzee cells that contained an SIV and allegedly contaminated the vaccine. A special meeting convened at the Royal Society (London) in 2000 invalidated these claims. In fact, production took place in the U.S. at the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia, and no chimpanzee cells were used.

Applying the tree-building tools developed by evolutionary biologists to ever-larger large datasets eventually permitted reliable dating. It became increasingly clear that the AIDS pandemic began when HIV descended from a chimpanzee SIV around 1900, 50 years earlier than Hooper’s imagined and now rejected scenario.

An alternative, far less controversial, proposal mentioned but not really pursued by Hopper was that the re-use of unsterilized needles and transfusion of unscreened blood drove the proliferation of HIV in Africa. These factors undoubtedly contributed to the HIV pandemic.

From HIV to COVID-19

Procedures developed and lessons learned from the investigation of the AIDS pandemic greatly facilitated scientific responses to the current coronavirus pandemic. The same tree-building methods derived from evolutionary biology permitted prompt tracking of the galloping progress of COVID-19 around the world.

As with HIV, rapidly accumulating mutations complicate monitoring efforts but also yield valuable data for tree-building. One particularly significant application was testing a proposal that this coronavirus had been artificially created in a laboratory in China. Earlier this year, using well-established methods for tracking origins, an international team of authors, including Eddie Holmes, effectively ruled out purposeful manipulation as the source.

References

Andersen, K.G., Rambaut, A., Lipkin, W.I., Holmes, E.C. & Garry, R.F. (2020) The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nature Medicine 26:450-452.

Faria, N.R., Rambaut, A., Suchard, M.A., Baele, G., Bedford, T., Ward, M., Tatem, A.J., Sousa, J.D., Arinaminpathy, N., Pépin, J., Posada, D., Peeters, M., Pybus, O.G. & Lemey, P. (2014) The early spread and epidemic ignition of HIV-1 in human populations. Science 346:56-61.

GBD 2017 HIV Collaborators (2019) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and mortality of HIV, 1980–2017, and forecasts to 2030, for 195 countries and territories: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study 2017. Lancet HIV 6:e831-859.

Gryseels, S., Watts, T.D., Mpolesha, J.-M.K., Larsen, B.B., Lemey, P., Muyembe-Tamfum, J.-J., Teuwen, D.E. & Worobey, M. (2019) A near-full-length HIV-1 genome from 1966 recovered from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue. bioRxiv 1-15. [subsequently published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A. 117:12222-12229]

Holmes, E.C. (2001) On the origin and evolution of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Biological Reviews 76:239-254.

Hooper, E. (1999) The River: A Journey to the Source of HIV and AIDS. New York: Little Brown & Co.

Kasper, P., Simmonds, P., Schneweis, K.E., Kaiser, R., Matz, B., Oldenburg, J., . Brackmann, H.H. & Holmes, E.C. (1995) The genetic diversification of the HIV TYPE-1 gag P17 gene in patients infected from a common source. AIDS Research & Human Retroviruses 11:1197-1201.

Keele, B.F., Van Heuverswyn, F., Li, Y., Bailes, E., Takehisa, J., Santiago, M.L., Bibollet-Ruche, F., Chen, Y., Wain, L.V., Liegeois, F., Loul, S., Ngole, E.M., Bienvenue, Y., Delaporte, E., Brookfield, J.F.Y., Sharp, P.M., Shaw, G.M., Peeters, M. & Hahn, B.H. (2006) Chimpanzee reservoirs of pandemic and nonpandemic HIV-1. Science 313:523-526.

Leigh Brown, A.J. & Holmes, E.C. (1994) Evolutionary biology of human-immunodeficiency-virus. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 25:127-165.

Little, K.M., Kilmarx, P.H., Taylor, A.W., Rose, C.E., Rivadeneira, E.D. & Nesheim, S.R. (2012) A review of evidence for transmission of HIV from children to breastfeeding women and implications for prevention. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 31:938-942.

Osterrieth, P.M. (2001) Vaccine could not have been prepared in Stanleyville. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 356:839.

Sharp, P.M. & Hahn, B.H. (2010) The evolution of HIV-1 and the origin of AIDS. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 365:2487–2494.

Worobey, M., Watts, T.D., McKay, R.A., Suchard, M.A., Granade, T., Teuwen, D.E., Koblin, B.A., Heneine, W., Lemey,P. & Jaffe, J.W. (2016) 1970s and ‘Patient 0’ HIV-1 genomes illuminate early HIV/AIDS history in North America. Nature 539:98-101.