Stress

From Stress to Genes, Baboons to Hormones

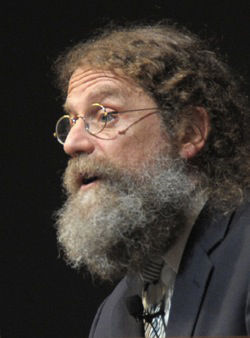

An Interview with Robert Sapolsky

Posted February 4, 2017

We act beneficently.

We act badly.

What governs? Yes, we know that heredity and environment interact but how potent are epigenetics really?

We know we should reduce stress but that's easier said than done. Is there help beyond mindfulness, God, and Xanax?

What in the world do baboons have to do with it?

Today’s The Eminents interview should help elucidate.

Robert Sapolsky is a winner of the MacArthur Fellowship, the so-called genius award, the McGovern Award from the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the Carl Sagan Prize for Science Popularization. He’s hung out at rather august places. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa in biological anthropology from Harvard, got his Ph.D. in neuroendocrinology from the Rockefeller University, and is now Professor of Neurology at Stanford. His books include the bestselling A Primate’s Memoir, The Trouble with Testosterone and Other Essays on the Biology of the Human Predicament, Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers, and the just-now-available-for-pre-order: Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst.

Marty Nemko: Behave is 700 pages long. As entertainingly as it’s written, perhaps not all readers of this article will read your book cover to cover. So, what’s the punch line?

Robert Sapolsky: The fascinating thing about our best and worst behaviors isn’t the behavior itself – the brain tells the muscles to do something or other – big deal. It’s the meaning of the behavior. Pulling a gun’s trigger can be an appalling act. But if it is suicidally drawing fire to save someone, it has an utterly different meaning. Placing your hand on someone’s arm can be an act of deep compassion or the first step of betrayal. The punch line? It's all about context, and the biology of context is vastly more complicated than the biology of the behavior itself.

MN: What’s the best approach for understanding human behavior at its best and worst; Neurobiological? Genetic? Evolutionary?

RS: All of the above. What happened in the milliseconds before a behavior to cause it? That’s in the neurobiological realm – that’s the first chapter of the book. What happened during the minutes before? That’s the realm of sensory stimuli of the nervous system – the next chapter. Hours to days before? Hormones influencing the sensitivity of the person to environmental stimuli. Weeks to months before? Neural plasticity. Years before: Prenatal environment and genes. And even further-back: cultural, ecological, and evolutionary factors.

MN: In considering hormonal effects on behavior, what are current views about that perennial villain of aggression – testosterone – and about the wonderfully pro-social oxytocin?

RS: Oxytocin is a Teflon hormone—bad news rolls off it. Oxytocin is lauded for how it promotes warmth, generosity, social bonding, cooperation, trust, and compassion. Give lab rats oxytocin and, according to that meme, they get better at talking about their feelings and sing like Joan Baez. Naturally, things are more complicated – Those groovy, pro-social effects of oxytocin apply to how we interact with in-group members. But, to out-group-members, oxytocin makes you crappier – less cooperative and more preemptively aggressive. It’s not the luv hormone. It’s the in-group parochialism/xenophobia hormone.

As for testosterone, it’s gotten a bum rap. Yes, it has tons to do with aggression but it doesn’t cause aggression as much as sensitizes you to the environmental triggers of aggression. Furthermore, individual differences in testosterone level predict very little about differences in aggression. Importantly, rather than promoting aggression, testosterone promotes whatever is needed to maintain status when challenged. If you’re a Siamese fighting fish, that’s probably going to indeed be aggression. But if you’re a human, in the right circumstance, it prompts someone towards making larger, conspicuous bids at a charity auction. It’s probably even the case that if you stoked up some Buddhist monks with tons of testosterone, they’d become wildly competitive as to who can do the most acts of random kindness. The problem isn’t testosterone and aggression; it’s how often we reward aggression. And we do: We give medals to masters of the “right” kinds of aggression. We preferentially mate with them. We select them as our leaders.

MN: So how should we think of humans as a species? Are we just another primate? What’s the most unique thing about us when it comes to social behavior?

RS: Well, we are just another primate but a very confused, malleable one. For example, most mammals are either monogamous or polygamous. But as every poet or divorce attorney will tell you, humans are confused--After all, we have monogamy, polygamy, polyandry, celibacy, and so on. In terms of the most unique thing we do socially, my vote goes to something we invented alongside cities – we have lots of anonymous interactions and interactions with strangers. That has shaped us enormously. For example, only humans invent moralizing gods who monitor our behavior.

MN: So where does the frontal cortex fit in to our best and worst behaviors?

RS: It’s in the middle of everything related to it. The frontal cortex is an incredibly interesting part of the brain – Ours is proportionately bigger and/or more complex than in any other species. It doesn’t even fully develop until age 25, which is wild! What does the frontal cortex do? Gratification postponement, executive function, long-term planning, and impulse control. Basically, it makes you do the harder thing.

It’s great to have a buff frontal cortex to do that harder thing—for example, help a person in need rather buy some useless, shiny gee-gaw. But often, it's easier to resist temptation with distraction, or to be so inculcated in doing the right thing that it’s automatic, outside the frontal cortex’s portfolio – Then it isn’t the harder thing, it’s the only thing you can do.

MN: What about genes?

RS: Don’t get me started. Yes, genes are important for understanding our behavior. Incredibly important – After all, they code for every protein pertinent to brain function, endocrinology, etc., etc. But the regulation of genes is often more interesting than the genes themselves, and it’s the environment that regulates genes. Almost always, genes are about potentials and vulnerabilities rather than about determinism.

MN: You have an entire chapter about the dichotomies that humans make between Us and Them. How important is that?

RS: Immensely. Brains distinguish between an Us and a Them in a fraction of a second. Subliminal processing of a Them activates the amygdala and insular cortex, brain regions that are all about fear, anxiety, aggression, and disgust.

That’s really depressing, actually. Until you appreciate something crucial – It is incredibly easy to manipulate us as to who counts as an Us, who as a Them. I think it is inevitable that we make Us/Them distinctions but there’s nothing inevitable about who counts as a Them.

MN: What explains our differential reaction to different Others. For example, if we’re a member of Race A, we may well react differently toward a person of Race B than toward a person of Race C?

RS: Susan Fiske at Princeton has wonderful work on this, showing that we tend to classify Us/Thems along two axes. The first is warmth: Is this group viewed as benevolent and well intentioned towards us. The second is competence: Is this group viewed as having the agency and efficacy to achieve its goals. From this she generates a matrix of differing attitudes:

- There are groups we rate as high in both warmth and competence — Us, naturally. Americans typically rate good Christians, African American professionals, and the middle class that way.

- There’s the other extreme, low in both warmth and competence. People typically give such ratings to the homeless or addicts.

- Then there’s the high-warmth/low-competence realm—the mentally disabled, the elderly parent sliding into dementia.

- And there's the complex categorization of low warmth/high competence. This is the hostile stereotype of Asian Americans by white America, of Jews in Europe, of Indo-Pakistanis in East Africa, of Lebanese in West Africa, of ethnic Chinese in Indonesia, and of the rich by the poor most everywhere. It’s the same low-high derogation: They’re cold, greedy, clannish---but, dang, they’re sure good at making money and you should go to one who is a doctor if you’re seriously sick.

The most important point of Fiske's work is that it provides a taxonomy for our differing feelings about different Thems -- sometimes fear, sometimes ridicule, sometimes contemptuous pity, sometimes savagery.

MN: You’re a modern-day Jane Goodall, having spent many summers, over 30 years, living with baboons. What would you says is that experience’s most important practical takeaway for a Psychology Today reader?

RS: If you care about your longevity and health, be a socially affiliated baboon who is better than high-ranking ones at walking away from provocations.

MN: Do you ever wonder whether we've ascribed too much explanatory power to Darwinian selection as causing changes in species?

RS: I think it's thoroughly explanatory....until you look more closely....especially at humans.

MN: You’ve studied stress for a long time. Everyone knows that excessive stress is unhealthy. But adrenaline-addicted people seek-out stress. Any thoughts on if and how to try to get such people to change?

RS: We all seek out stress. We hate the wrong kinds of stress but when it's the right kind, we love it -- We pay good money to be stressed by a scary movie, a roller coaster ride, a challenging puzzle. The gigantic challenge is the magnitude of the individual differences in the optimal set point for "good stress.” For one person, it's doing something risky with your bishop in a chess game; for someone else, it's becoming a mercenary in Yemen. As long as experiencing your optimal level of good stress doesn't damage others, it's hard to objectively define where normal enjoyment of stimulation becomes adrenaline junkiehood.

MN: You've looked at the age-old question of free will versus determinism. Where do you come down?

RS: My guess is if a reader actually makes it to the end of the book, they’ll view free will as being as implausible as I do. Or if they still cling to the notion of free will, that it lives in some pretty uninteresting places that keep getting crammed tighter and tighter by science.

MN: You’re 59. What’s ahead for Robert Sapolsky?

RS: Oh, the usual -- a bigger prostate, a not-very-mature sense of dread at the symbolic import of turning 60, plans to be more vigilant about not repeating the same joke in a lecture. And I'll admit to being pretty interested to see how this new book of mine is received.