Motivated Reasoning

Ideology Is a Breeding Ground for Motivated Reasoning

Excessive adherence to ideological thinking can be problematic.

Posted July 13, 2022 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Strongly held biases and motivated reasoning can lead to errors in decision-making.

- Ideological thinking can contribute to these errors and is composed of both a doctrinal and relational component.

- Better understanding of the way both elements of ideological thinking impact decision-making could improve societal discourse.

I’ve written several posts about biases and motivated reasoning. Although both can be adaptive for survival and generally offer more upsides than downsides to decision-making, both can also lead to decisions that rely on faulty reasoning or are inconsistent with a preponderance of evidence. Adherence to an ideology (or ideological thinking) may make us susceptible to such erroneous decisions, and it was a topic that Zmigrod (2022) recently dove into in Perspectives on Psychological Science.

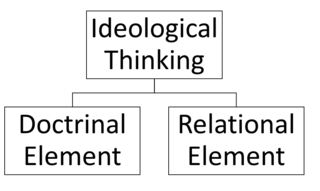

Zmigrod integrated research from several disciplines to develop a taxonomy of ideology. In her review, she pointed to two key elements of such thinking: a doctrinal element and a relational element (see Figure 1 for an adaptation of her visual).

The doctrinal element is akin to the dogma of the ideology. It encompasses both the beliefs inherent in that ideology as well as the rules that govern thinking and action. For example, religious ideologies possess both the beliefs that underlie that religion (belief in God, Allah) and the rules that govern how to make decisions within that religion (deciding what is right and wrong). Thus, the doctrinal element of ideological thinking provides the underlying values, beliefs, and rules that guide decision-making, forming the frame of reference through which ideology adherents navigate a host of decisions.

The relational element is akin to a bias or favoritism shown toward others who share a given ideology and negativity shown toward those who do not[1]. For example, those who strongly identify with a political ideology will be more likely to have positive views of those who share that ideology and negative views toward those who do not. This relational bias can predispose ideological thinkers to accept arguments put forth by adherents much more readily[2] than arguments put forth by those who hold different beliefs.

There are two key implications of the taxonomy put forth by Zmigrod that warrant some comment. The first implication is that the doctrinal element alone is insufficient to create an ideology. Although she argues that some doctrines could be sufficient to represent an ideology, such as capitalism or communism, their impact increases when there is a negative view toward those who do not adhere to that ideology, especially as that view begins to approach a degree of animosity or hostility. As such, she argues that adherence only to the doctrinal element without a corresponding relational element “may not be of genuine psychological interest” (p. 6).

I disagree because her perspective assumes we’re only interested in studying ideologies if they “breed intergroup tolerance and hostility” (p. 6). I would argue, though, that adherence to the doctrine of an ideology, even without the relational element, will influence decision-making—especially in terms of the way adherents approach various trade-offs—and is worthy of study by researchers. Many disagreements that we see among decision-makers, especially when addressing complex issues (climate change, COVID response), are a result of adherence to different doctrinal rules.

The second implication is that there may exist some crucial differences between those who espouse only the doctrinal element of an ideology and those who also espouse the relational element. For example, it is possible that people who adhere to the doctrine of veganism may differ in terms of the degree to which they hold negative views toward those who do not adhere, “and it is the difference between these two groups that yield fascinating lines of research” (p. 6).

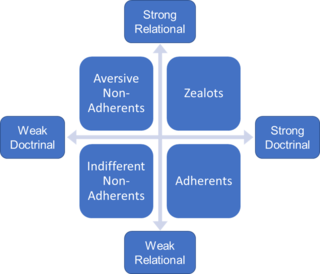

I absolutely agree with Zmigrod’s perspective on this. Ideological thinking could be conceptualized as interacting continua (as shown in Figure 2). Those high in both the doctrinal and the relational elements would be akin to zealots (vegan who looks down on non-vegans), which is different from those who simply adhere to an ideology without espousing the relational element (a vegan who does not look down on non-vegans). The other side, which Zmigrod doesn’t really address, includes individuals who do not adhere to a given ideology and are either:

- aversive to those who do (a non-vegan who actively dislikes vegans)[3]

- indifferent to those who do (a non-vegan with no dislike of those who choose to practice veganism)

Incorporating a continuum-based conceptualization opens the door to more research possibilities than Zmigrod acknowledges in her theoretical article (which is worth the read). It offers the potential to explore how distinct categories of adherents and non-adherents approach decisions related to a given ideology’s doctrinal element, the likelihood of adherents to construct arguments that are respectful of the views of non-adherents, and how open-minded non-adherents are likely to be to such arguments.

We need look no further than the current state of political discourse in the U.S. for examples of what happens when extreme zealotry dominates the conversation. A better understanding of how it develops and how to mitigate it could benefit society at large.

References

Footnotes

[1] This phenomenon has been referred to many things, such as in-group favoritism or ingroup-outgroup bias.

[2] And with much less critical thinking

[3] There might also be differences between aversive non-adherents who are aversive because they hold strong opposite beliefs (e.g., a capitalist who abhors communists) vs. those who are aversive due to negative experiences with zealots.