Suicide

ADHD and Suicide Risk

COVID-19 has spotlighted concerns about mental health, suicide risk, and ADHD.

Posted September 11, 2020 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Trigger Warning: If you or someone you know needs someone to talk to, this 24/7 resource is available: National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 1-800-273-8255 (273-TALK).

September is National Suicide Prevention Month, and the timing is helpful. Mental health, and especially suicide risk, have skyrocketed as a concern. An AP news headline today notes that young people in the U.S. report worsening mental health due to COVID-19. Underscoring the risks, a literature search for “suicide and COVID-19” produces over 150 scholarly papers appearing in the past six months alone, addressing concerns from around the world. However, few of these have yet been able to measure actual suicide rates in the pandemic; most reports are anecdotal or offer prevention recommendations. Reassuringly, one study in Japan showed no change in youth suicide during the March to May period in 2020 (school closure) compared to 2018 or 2019.

Yet, suicides appear to have increased during prior pandemics. It is still early—risk will increase as isolation and financial distress continue and wear down coping skills in individuals and communities. Suicidal thoughts increased from April through June of 2020 for those in the U.S. who were under lockdown or social isolation restrictions.

Likewise, the incidence of depression or anxiety tripled from March-May 2019 to March-May 2020 in one survey of over 300,000 adults in the United States. A recent survey by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 40 percent of adults in the U.S. reported worse mental health due to COVID-19 and 11 percent had serious suicidal thoughts. Rates were higher among Hispanic and Black respondents and youth. These findings suggest that risk is still increasing, as ideation can lead to subsequent attempts.

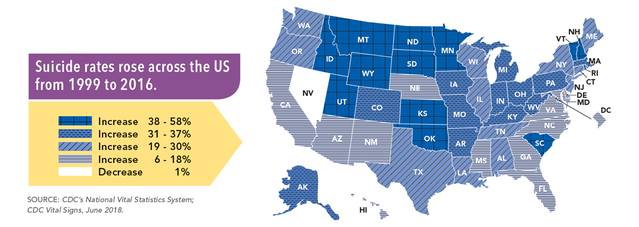

The seriousness of suicide risk can be startling. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for individuals ages 10 to 34 in the United States (after unintentional injury/accidents), with males at higher risk than females and adolescents at higher risk than children. The risk peaks in adolescence and young adulthood too, with 4 to 9 percent of youth making a suicide attempt at some point in their lives. Suicidal ideation is far more common—about 17 percent among adolescents worldwide. Thus, only a small fraction of youth expressing suicidal thoughts will actually complete suicide. Although suicide rates have declined in the past decade worldwide, they have increased in the United States (see chart).

Further, the risk of suicide will clearly increase during the current crisis due to financial distress and social isolation, as well as the associated increases in domestic violence, alcohol consumption, and access to lethal means.

Especially vulnerable are those on the front lines (e.g., health care and other essential workers), young people, those who have lost loved ones, and those with pre-existing mental health vulnerabilities, including individuals with ADHD.

Any self-harm behavior (including non-lethal cutting, ambiguous and definitive suicide attempts), as well as persistent suicidal ideation, are of concern: All of these increase the risk of later suicide. Depression, substance use, or other mental health conditions are usually involved in suicide. Children with ADHD have a three-fold risk of eventual serious, life-threatening accidental injury; when depression, ADHD, and substance use are combined in young people, suicide risk can be increased by as much as 10-fold.

For young people, important immediate risk factors for suicidal ideation or attempt include mental health struggles and recent acute psychosocial stressors. Additional important risk factors include maltreatment or abuse, depression, impulsivity, substance use, peer suicide (beware of “contagion” if a suicide occurs among your teen’s peer group), feeling isolated or hopeless, a recent major loss (a breakup with a partner; peer rejection), access to lethal means, and lack of access to mental health support (e.g. a counselor to talk to).

Most suicides are the product of a temporary “low”—most individuals who want to die today will feel differently in the future. Therefore, it makes sense to do everything we can to prevent suicide. Many prevention strategies are available for families, schools, and communities. Counselors can adjust these strategies with you to address either immediate, acute risk versus low-grade, ongoing risk. For teens, positive communication with parents is a fundamental resilience factor, but many others are available. If you are worried about suicidal risk in yourself or a loved one, consult a pro right away. You can also call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 (273-TALK).

The effectiveness of both community-based and clinical suicide prevention has improved notably in the past decade, so policymakers need to look carefully at the range of emerging recommendations. What can a clinician or an individual do to protect their teen or young adult? What can young adults do to support peers? Here are some basics:

- Listen to warning signs. Yes, youth do sometimes make manipulative threats. But 80 percent of teens who attempt suicide give warning signs first, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. If your child is feeling hopeless or thinking more than occasionally about suicide, or has suicidal ideas that are potentially deadly, consult a counselor about how to create a safety plan (not just a safety contract).

- Be aware of risks other than explicit suicidal talk. These include for teens: periods of high stress; recent significant loss (e.g., a break-up) or traumatic event; signs of depression (hopelessness, loss of interest); feeling left out or lonely; feeling like a burden to others.

- If someone is actively acutely suicidal (afraid they might do it, has a realistic and lethal plan or idea how to go about it, or access to lethal means), try not to leave them alone. Make a plan for accompaniment until counseling or professional evaluation can be obtained.

- Keep emergency call line numbers handy.

- Be aware that intoxication adds to acute risk by reducing inhibitions.

- Restrict access to lethal means in your own home:

Lock up the medicine cabinet: A common way teens injure or kill themselves is through taking pills from parents’ cabinets including Tylenol (acetaminophen; an overdose of acetaminophen can be lethal especially if not treated within a few hours—acute liver failure is extremely dangerous). Lock up your medicines, including all over-the-counter drugs. At my university, health care providers have begun providing families of at-risk teens free emergency lock bags; you can purchase lockable and tough medication pouches for about $20, or a larger lockbox for the same purpose.

Firearms: Review and double down on your firearm safety plans. The literature suggests that we, as parents, are not accurate at knowing our child’s knowledge of, or behavior around, guns when we are absent. Avoid denial. If you have a child with ADHD, be extra thorough in educating or training your children in gun use and safety, and triple-check and regularly review your gun storage and safety procedures.

Medication treatment: Talk to your doctor about the pros and cons of stimulant treatment for your teen. Stimulants (like Ritalin) reduce the risk of physical injury for kids with ADHD, but they come with a warning that suicidality is a contraindication. Yet a national population study from Taiwan reported reduced suicide attempts in youth who had been treated with stimulants in the last three months (however, suicide rates in Taiwan are different than in the U.S.).

- Don’t hesitate to consult a pro. Increasingly effective counseling is available for youths and young adults with self-harm behavior or escalating suicidal thoughts. If in any doubt, then it is worth it to seek some counseling from a trained counselor for suicidal risk or self-harm.

Our recently-established Center for ADHD Research at Oregon Health and Science University and the generous matching gift campaign associated with it are all motivated in part by strong concern about youth suicide, driven in part by the dangerous overlap of impulsivity, discouragement, addiction or substance use, and rule-breaking that so commonly occur in the ADHD population. They amplify developmental risks in the teen and young adult years. Our collaborators are actively studying suicidal risk and prediction.

Please note: Dr. Nigg cannot advise on individual cases for ethical, legal, and logistical reasons.

References

Asarnow JR & Mehlum L. (2019). Practitioner Review: Treatment for suicidal and self-harming adolescents - advances in suicide prevention care. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines, 60(10), 1046–1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13130

Furczyk K & Thome J. (2014). Adult ADHD and suicide. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 6(3):153-8.

Gunnell D, Appleby L, Arensman E, et al. (2020). Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 7(6):468-471. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30171-1

Impey M & Heun R. (2012) Completed suicide, ideation and attempt in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 125(2):93-102.

Isumi A, Doi S, Yamaoka Y, Takahashi K, Fujiwara T. (2020). Do suicide rates in children and adolescents change during school closure in Japan? The acute effect of the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic on child and adolescent mental health [published online ahead of print, 2020 Aug 23]. Child Abuse Negl. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104680

Killgore WDS, Cloonan SA, Taylor EC, et al. (2020). Trends in suicidal ideation over the first three months of COVID-19 lockdowns [published online ahead of print, 2020 Aug 17]. Psychiatry Res. 293:113390. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113390

Nordentoft M & Erlangsen A. (2019). Suicide-turning the tide. Science (New York, N.Y.), 365(6455), 725. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz1568

Turecki G & Brent DA (2016). Suicide and suicidal behaviour. The Lancet, 387, 1227–1239.

Twenge JM, Joiner TE. (2020). U.S. Census Bureau-assessed prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in 2019 and during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jul 15]. Depress Anxiety. 10.1002/da.23077. doi:10.1002/da.23077

Uddin R, Burton NW, Maple M, Khan SR, Khan A. (2019). Suicidal ideation, suicide planning, and suicide attempts among adolescents in 59 low-income and middle-income countries: a population-based study. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 3 (4): 223–233. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30403-6. PMID 30878117.