Memory

How to Improve Your Memory Instantly: Part Two

Last time we explored memory "pegs". Let's go on a "journey" this time.

Posted March 3, 2014

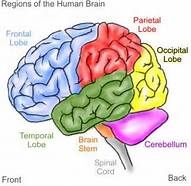

WARNING UPFRONT:If you have not read my last article of this series, you'll likely be confused (and maybe even downright skeptical) as this particular article ticks along. I previsously wrote about the power of using the occipital lobe to aid memory. This lobe, located in the back of your head, is protected by your skull quite nicely. Reach around right now and locate it by feeling for a knot or a bump in the cranium several inches above your neck. (Ladies, sorry, yours will not be as pronounced as the men reading this. That’s one of those anatomical gender differences.) Just above that bump—yep, right there—is your occipital lobe.

The occipital lobe is what gives us the power to visualize images in our minds. Yes, it is also the place where, for all intents and purposes, vision itself is processed once data comes streaming in from the optic nerve. But never mind the latter, it’s the power of visualization we will use again today to help harness our brain’s greater potential for recall of information.

Many pointed out in the comments of the other article that the structure I demonstrated was called a “peg” system. Indeed, that is correct and that system is many many decades old. In that demonstration, we used a number-rhyming organization loosely based on a nursery rhyme to connect data (e.g. grocery list items) to a list of numbers, one through ten. The advantage of the peg system, as many of you confirmed for me, is that it allows for a direct and immediate recall of the relationship between the data and the number. Thus, you were able to note that #3 was “dog food” or, equally easily, that “dog food” was the third item on the list.

Today’s technique is a tad different in that it makes no use of these mnemonic “pegs.” The system we’ll explore today is one that I learned many years ago as “journeying” although, again, others have noted that this is merely a form of a broader technique called the “loci” method. As that name implies, the loci technique seeks to make use of places or localities familiar to you already as a means of pinning information to memory. Before we get started on the explanation, I should note for you a few things.

- This technique is extremely powerful in that it potentially allows a larger amount of information to be coded without the use of those number-rhyme type “pegs”. Still…

- In my own experience, it also takes a bit more practice to harness. (This should not be a deal-breaker but be aware that if you are comparing it to the peg system of the previous article, it will not be as immediately “user-friendly”—for at least some of you, perhaps.)

- Unlike the previous number-rhyme peg system, this technique doesn’t allow for that immediate recall of, say, number six on a list. Journeying requires you to trace the steps from one to five in order to name item number six. (Again to me, depending on what you are trying to recall, that should not be a deal breaker either.)

- Journeying, indeed the loci-method in general, is powerful because we are still utilizing and accessing massive amounts of our brain’s hardware—that occipital lobe—to create memorable images.

Let’s start by getting the data we’ll seek to memorize. At the end of this article is a list of 25 items. In keeping with the theme of last article, I’ve opted to make many of them grocery store items. You’ll also note, however, that I’ve added some typical errands that a person might have to do in the course of a day. If you are able to, you might wish to copy and paste that list into a document for consideration later on—or, if not, you may simply scroll up and down to compare my description of the technique to this list I’ve created.

Now completely leaving aside that list (just for the moment), I want you to think of some sort of “trip” or traveling routine you perform every day of your life. Every morning, for example, I wake up, leave my bedroom, and hit the bathroom for a shower and a shave. Finished and dressed, I pass by my son’s room and a guest bedroom as I head downstairs to the kitchen where I make coffee. I sit down in the dining room at my computer and chug the caffeine while I review my day’s plans. And then I go to the living room where I feed the cat. Finally, I head out the door for school, leaving by way of the side door that opens onto a screened porch where we have some wicker furniture and our mailbox hangs on the brick wall.

You, dear reader, need not think of your own home. Perhaps the daily trip you thought of was your daily work commute—leaving your house, driving past the neighbors’ homes, that Starbucks one one corner (McDonalds on the other!), arriving at the train depot. Maybe, like me, you’re a runner and you can quite easily picture all the twists and turns and landmarks of your daily four-mile route. Perhaps you drive a bus and that’s the route in your life you know like the back of your hand. It doesn’t matter.

What does matter—to make the journeying memory technique really work—are those details you’ll recall. You know… that neighbor’s funky house, that Starbucks on the corner that used to be an old bank,… the paisley shower curtain, that coffee maker on the counter right next to the sink, the cat bowl next to the couch. In my experience, you’ll want at least 10 to 12 such distinct landmarks, and here’s why: those details will effectively become the mnemonic pegs that link to your data. How, you ask?

Crazy as this seems, what you’ll do is create detailed and exciting, bizarre, humorous, scary, titillating, you-name-it visual images that pair the data you want to recall with each of the landmarks on your “journey.” Then you’ll mentally trace this journey later on when you want to recall that data.

Thus, if I were considering only the first ten or so items on the list I’ve created for you, I would associate the first (plastic cups) with my morning shower (the first of my landmarks). I imagine innocently pulling the shower curtain aside to turn on the faucet…and being utterly shocked awake that a plastic cup is bathing in the tub. He’s right there! I’d imagine his thin arms holding my loofah (grr!), vigorously rubbing away at some lipstick left on his rim. He would even be complaining about it and yelling at me for some “d@mn privacy!” Remember, the brain likes novelty, not ordinary. The crazier and more detailed that image is, the better.

I’d slam the curtain shut—or maybe I’d fill him with cold water from the tap just to get even—and then I’d move on with my journey to the second item in the list and its associated landmark. I’d note that, as I pass my son’s room, there on his door where the usual “Knock, please” sign hangs is… a pizza?! And it’s huge. The grease is dripping down the door and the pepperoni is on the floor. What a mess. It’ll take forever to clean that up. (Maybe I’ll make my son do it, heh heh.)

I’d continue in like fashion until all ten(ish) items were securely cemented via that visualization. WhenI I'm srure they're there, it's time fot

And yet many of you have noted that there are 25 items on the list below—and I said you only need about a dozen landmarks. So what then? It’s an easy fix: For lists that are longer, all you need do is combine your images in pairs.

So, starting again, I’d pull aside that shower curtain and there, revealed in all their glory, would be a pizza and plastic cup caught in the middle of a, uh,…romantic interlude. (Whaaaa?!) The pizza is wrapping the cup in a full embrace—I can hardly see the cup at all for cryin’ out loud! This time it’s the pizza that yells at me for privacy—or maybe she doesn’t (oooh).

Again it's the mental investmetn that makes it count, pairing the items with my landmarks (Hey, why are the detergent box and Super Glue fighting over who gets to eat cat food first? There’s plenty to go around, guys!) until I arrive at the list of errands.

When you get there, don’t let the verbs bother you—just picture a noun that goes with each. For “get birthday present” I might picture the actual gift itself, sure. Or maybe I’ll imagine the the wrapped box, bow and all (Wait, isn’t it a tad large? It takes up the entire porch!). When I go to put the Netflix DVD in the mail—yep, you guessed it—it cries and begs me not to send it away (“I’ll never see you again, will I?”). Sigh. It’s hard, yes, but in you go as I head out the door.

The wonderful and powerful thing about using the journeying technique is that you likely have many different “routes” or “trips” you can take. I have one that documents my morning routine. But I also have: that favorite four-mile running loop I enjoy so much; the route my family walks when we go to our favorite restaurant a mile away; and my own morning commute to work. Each “journey” and its associated landmarks can become a mnemonic device for you, each assigned to a different list of data.

Ladies and gents, the key to this particular mnemonic device is practice. Try these journeys at night as you lay in bed before sleeping. Trace them with as much detail as you can. Cement those details in your mind. In this case, practice makes perfect.

Next time, we’ll consider ways to deal with more nonrepresentational concepts, such as the meanings of foreign words or abstract nouns. Stay tuned!

Want more? Follow me on Twitter for the latest!

YOUR (DATA) LIST:

- plastic cups

- frozen pizza

- grapes

- deli meat (turkey)

- shampoo

- dog biscuits

- detergent

- nail polish

- ice

- garlic

- cans of soup

- celery

- Super Glue

- light bulbs

- Hershey’s bars

- pepper

- floor wax

- batteries

- gift card

- eggs

- deposit checks

- get car inspected

- do laundry

- get present for friend’s birthday

- put Netflix DVD in the mai