Career

Personal Agency Drives a New-Look Motive Hierarchy

The “Maslow pyramid” was magnificent but confining. Put yourself in charge.

Posted April 23, 2020

What motivates people (including you)? This age-old question is everlasting due to so many possible and multi-faceted answers.

What’s your first thought in reacting to that question? For many, it's a pyramid with five colored layers displaying Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs. Physiological needs comprise the base, and self-actualization is the crowning glory. Introduced in the 1940s and popular by the 60s, Maslow’s theorizing remains prominent and respected to this day.

Maslow never used the iconic pyramid to portray his hierarchy. It is not impertinent to use contemporary research (many others’ and mine) to update and revise the pyramid in useful ways that still respect Maslow’s contributions.

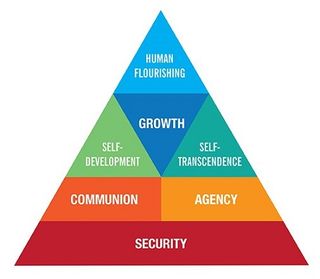

The new-look hierarchy, shown in the figure, departs from Maslow’s by highlighting personal agency as the action-oriented, self-guided driver of what people do. It departs also via different motives including, at the pyramid’s peak, human flourishing — subsuming other people’s flourishing as well as one’s own.

A Revised Hierarchy of Human Motives

Security motives anchor the hierarchy at its base and subsume Maslow's two lower-order needs. His physiological needs included food and water, and (in modern society) safety needs cause us to seek indoor living, health care, and insurance. Behaviors driven by security motives are quite evident (but not universal) during the COVID-19 pandemic and will become more so as climate change accelerates.

At the next level up are the complementary motives of communion and agency, the “Big Two” of social cognition. Communion captures Maslow's love, belongingness, and social needs, and involves integrating the self in a larger social context. Agency is the desire to expand oneself, achieve, and individuate, and subsumes needs for competence, control, and mastery. It also is a bridge to self-directed, high-leverage action.

Personal agency puts people in the driver’s seat, allowing escape from confining habits, unthinking routines, and circumstances controlled largely by other people's expectations and other situational demands. Personal agency helps people choose their own paths and influence short-term outcomes plus longer-term destinies.

Bandura's social cognitive theory identifies the core belief in personal agency as self-efficacy—confidence in our ability to perform a task or achieve a goal. Efficacy beliefs influence the decisions people make, the goals they choose, the effort and persistence they apply over time, and the courses their lives take. Furthermore, they affect whether, when, and how people pursue the higher-level growth motives: self-development, and self-transcendence.

Self-development emphasizes strengthening and applying one's knowledge, talents, and capacities. It captures the primary path to self-actualization as Maslow described it, and includes personal and professional growth and accomplishment.

Differing from self-development, self-transcendence serves externally-directed motives that benefit other people and causes. Maslow wrote that human potentialities could be individual or collective and even species-wide; he described some but not all of his self-actualized study participants as unselfish people desiring to help the human race. Commensurately, the motive hierarchy identifies self-transcendence as an alternative to self-development — a high-level motive manifested in choices and behaviors that create positive outcomes for others.

Self-development and self-transcendence support and drive growth and flourishing in oneself and others. People can satisfy these (as well as lower-level) motives through naturally-occurring developmental processes but also via agentic choice and self-determination.

Human Flourishing Is the Pinnacle

In theorizing about self-actualization, Maslow drew from the humanistic psychologists of the time. He also credited Aristotle's concept of eudaimonia: a higher calling than hedonic happiness in which people pursue and realize their purest and best (virtuous) selves. Flourishing research teaches us much about eudemonia, elaborating on the highest levels of the motive hierarchy.

Human flourishing is a state of complete human well-being. Flourishing means doing well or being well — self-realized, fully functioning, and purposefully engaged — in:

- Physical and mental health, including self-acceptance and life satisfaction

- Purpose in life

- Character and virtue

- Positive social relationships

- Autonomy and environmental mastery (for instance, feeling competent and in control)

- Personal growth

Each of these indicators is an end in itself, often a means to other ends, and a nearly universal desire.

Pathways to Flourishing

At least four contexts—family, work, education, and religious community— offer pathways to multiple flourishing criteria. Within and across contexts, flourishing can appear via circumstantial or self-generated opportunities. The paths to flourishing include progressing from lower to higher levels, pursuing meaningful projects by well-doing, activating free traits, and proaction.

Progressing from lower to higher levels. The pathways to flourishing open most fully when lower-level needs are satisfied in the moment and over time. The foundation of security, and therefore a condition for sustained flourishing, is access to resources—financial, medical, social, and natural/geographical—sufficiently secure to pursue the higher-level motives.

Pursuing meaningful projects by well-doing. Flourishing stems from well-chosen actions—what Professor Brian Little describes as ”well-doing,” manifested through the sustained pursuit of personally-valued core projects. Activities that are fun and pleasurable promote hedonic, satisfaction-based well-being. In contrast, a more profound, potential-actualizing, eudaimonic well-being comes from pursuing projects that satisfy higher values and purpose.

Activating free traits. Doing well in life, work, and meaningful projects demands a vast repertoire of behaviors and performances. Our personality traits—whatever we think they are, or however "tests" might score us—fit comfortably with some, but certainly not all, of these demands.

What may be the most important trait of them all is what Professor Little calls free traits: the flexibility and ability to adapt and deviate from our natural tendencies when circumstances invite it. A prime example is a person labeled an introvert who does well in a presentation or a big social event, even when preferring to be in the audience or at a smaller gathering.

As stressful and uncomfortable as our challenges can feel, breaking the confines of one’s dispositions can have eudaimonic effects. Free traits help us grow and flourish in domains that we thought were beyond the bounds of our competence.

Proaction. Bandura's social cognitive theory is both realistic and optimistic about people’s abilities to agentically choose and shape their desired futures. Extending his theory to the workplace, management researchers study the meaning and consequences (net positive but often risky) of behaving proactively—that unique class of behavior that overrides situational influences, transcends constraints, changes current trajectories, and forges new paths.

Proaction is the self-chosen exercise of agency. Proaction is purposeful and future-focused—forethought being the temporal extension of agency. When people behave proactively, their goals are to create positive change in self or circumstances, with personal benefits to oneself (self-development) or other people (self-transcendence). In combination, this duality generates human flourishing in the broadest and most meaningful sense.

Conclusion

As Maslow applied his psychological theorizing to the business world and beyond, he grew frustrated when managers and management scholars ignored his vision of an enlightened and engaged citizenry. He wrote that a good society is a psychologically healthy one that gives its members the best chances of self-actualizing. He would have valued workplaces and communities that:

- Satisfy security motives;

- Support healthy and productive levels of personal agency and communion;

- Provide opportunities for self-development and self-transcendence, and

- Contribute to widespread human flourishing beyond and across organizational and geographical boundaries.

The test of leadership, Maslow believed, is the effect of policies and actions on people's behavior outside of work, in the community. The motive hierarchy emphasizes personal agency as a springboard to self-development and self-transcendence and flourishing for self and others. If leaders and others help create workplaces and communities in which people thrive, the hierarchy can contribute to an even more empowering Maslow legacy.