Mind Reading

A How-To Guide for Boosting Your Mind-Reading Powers

You don’t have to be a psychic to read someone’s mind.

Posted May 26, 2012

Psychologists make a living out of predicting what people will do. By mastering the science of behavioral predictions, we can help everyone from advertisers to therapists anticipate how people will respond in a given situation. Unlike the evil villains of sci-fi movies, psychologists are obligated to use this information for ethical purposes. We are trained to use the scientific method to make our predictions. We develop our powers to predict behavior through observation, training, and experimentation.

For the average individual, the goals of predicting people’s behavior are far more practical. You want to know whether to take a risk and invite someone you’ve just met to join you for a meal or perhaps just a cup of coffee. Before you do that, you most likely would like to be fairly sure that your invitation will be met with an enthusiastic "yes" rather than a flat-out rejection. Perhaps it’s a work-related situation. Are you about to close a sale, land a new job, or want to be granted a day off? You’d like to know ahead of time whether the client, employer, or boss is inclined to go along with your wishes. Even in less clutch situations, it would be nice to predict the behavior of people you don’t know very well or will never meet again. Will the woman ahead of you in line at the checkout counter allow you to scoot ahead when you’re running late or will she call over the store manager and complain about your rudeness?

These are just a few of literally thousands of interactions we have in our daily lives in which we have to probe into the recesses of someone else’s mind and anticipate what he or she will do. From high-stakes situations to the relatively mundane, having mind-reading powers would certainly seem like a worthwhile ability to possess.

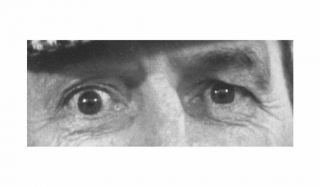

Fortunately, the ability to figure out what someone else is thinking doesn't require special magical abilities nor do you have to be a detective with the sleuthing powers of a Sherlock Holmes. You just have to be able to look into their eyes. Developed by University of Cambridge psychologist Simon Baron-Cohen, the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (RMET) is an online tool that you can easily use to diagnose and –most importantly- improve your mind-reading ability. When presented with a series of 36 pairs of eyes, you simply have to choose which of four emotions the individual is communicating. I've provided the link for the test at the end of this article.

The eyes and the areas surrounding them are the most expressive region of a person's face. Once you learn to read the person's emotions through the eyes, you're only a few small steps from predicting that person's behavior. An angry boss won't grant you a raise or even an extra day off but one who's in a generous mood won't hesitate to grant or consider granting your request. A bored prospective romantic partner will find a million reasons to avoid committing to a first date but one whose eyes communicate a glimmer of interest is likely to accept your invitation without hesitation. The harried shopper in front of you at the grocery store will never get out of her way to accommodate you, but if you can correctly guess her mood from her eyes, you’ll know whether even to bother to ask for the favor or just resign yourself to getting home a few minutes later than you hoped.

Judging another person’s mental state, also called having a “theory of mind,” is an important skill that, for most of us, develops early in life. Some individuals show lags in this ability, though, or never develop it at all. In fact, the RMET shows some success in identifying adults who score high on the autism spectrum. Low REMT scores may also play a role in alcohol dependence. A study by Belgian researchers Pierre Maurage and colleagues (2011) supports a theory that individuals with alcohol dependence have deficits in facial recognition, including detecting complex emotions.

Researchers are also finding a number of novel uses for the test. In one fascinating study, Rostock University (Germany) researchers Gregor Domes anc colleagues discovered that men who were given oxytocin, one of the “love” hormones (to put it crudely), had higher scores on the RMET than controls who given placebo.

Being able to read emotional cues through the eyes is also the first step toward responding empathically to other people. If you know how they’re feeling, you are more likely to be able to help them feel more understood by your words or gestures. Being able to listen with active empathy, furthermore, can help you enrich your intimate relationships.

In keeping with full disclosure, I should point out that inferring correctly an individual’s inner state from subtle outward cues in the eyes is not the same as the type of “mind-reading” that a stage psychic would demonstrate. You can infer someone’s mood, but not that person’s actual thoughts. However, accurately reading people’s moods is a first step toward predicting their behavior and perhaps gaining insight into the content of what they’re thinking. Start with an accurate reading of emotions, add in other cues you can gain from body language, listen to what a person says, and then take a careful look at the context, and you’re well on your way to predicting what will happen next.

You can practice your skills on everyone from your best friend to unassuming strangers. Let's start with the stranger. For example, you’re in the waiting room of your dentist’s office. You can be more or less certain that the person with the preoccupied look in his eyes and taking frequent deep breaths is worried about the procedure he’s about to undergo. The eyes + body language + dentist’s office give you a pretty good window into his mind. Without appearing nosy or intrusive, see if you can find a way to ascertain if your mind-reading is on target by starting up a friendly, but neutral, conversation. The same eyes and body language in a different context (such as standing alone in front of a movie theater entrance) would lead you to a different conclusion about his thoughts, namely that he’s afraid his partner will either be late or not show at all. You might not be able to stick around to find out the outcome, but if you can (without seeming creepy) you can see how close you were to reading his psychological state.

Stage psychics don’t leave much to chance, and many unfortunately engage in a little behind-the-scenes snooping to improve their hit rates. For example, they may get crucial personal details from a friend of someone they intend to put on stage seemingly, but not really, randomly. “Cold” psychic readings, rely on a little legerdemain known as the “Barnum effect,” in which the mind-reader starts by uttering a series of bland, generic statements that could apply to almost anyone. Then they put their RMET-type skills to work to refine their pronouncements. If you react with a slight emotional cringe to a Barnum-type statement such as “You’re concerned about the health of someone you know,” the psychic will pursue that line of questioning because the worry will invariably show itself, however slightly, in your eyes. If you show no reaction, the psychic can simply claim that “perhaps it isn’t someone you know well, but there is someone in your life with health problems” and the statement will certainly be true. Who doesn’t know someone with health problems?

Of course, the better you know a person, the more accurate your predictions should be. For people you know well, the best predictor of future behavior is past behavior. If your boss has never granted you a single one of your requests, it won’t matter whether you read irritation or amusement in between the nose and eyebrows. Chances are you won’t get what you want regardless of the boss’s mood. However, as long as a person shows a range of behaviors and you can learn which behaviors go with which facial expressions, you’ll have a better chance of timing your request so that it matches your boss’s good mood. Similarly, with your closest friends, you can sense even the slightest look of irritation because you know what pushes their buttons. If you think you're the cause of the irritation, you can quickly work to repair the damage.

Whether you know another person well or not, the lessons you can gain from the REMT will train you to focus your attention first on the eye region as your starting point for making your behavioral predictions. Even if the target of your prediction has a poker face worth a Lady Gaga serenade, the beauty of the REMT is that it distinguishes between very subtle emotions as reflected in the eye region of the face. You don’t need much practice, I would imagine, in distinguishing “angry” from “happy.” However, being able to distinguish, “irritated” from “sarcastic,” is a valuable eye-reading skill that can benefit from training.

With this background, you’re ready to take the REMT for yourself. If you’re not happy with your score, don’t worry, keep taking the test and you can definitely improve your “Eye-Q.”

Follow me on Twitter @swhitbo for daily updates on psychology, health, and aging. Feel free to join my Facebook group, "Fulfillment at Any Age," to discuss today's blog, or to ask further questions about this posting.

Copyright Susan Krauss Whitbourne 2012

References:

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Hill, J., Raste, Y., & Plumb, I. (2001). The 'Reading the mind in the eyes' Test revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Journal Of Child Psychology And Psychiatry, 42(2), 241-251. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00715

Domes, G., Heinrichs, M., Michel, A., Berger, C., & Herpertz, S. C. (2007). Oxytocin Improves 'Mind-Reading' in Humans. Biological Psychiatry, 61(6), 731-733. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.015

Maurage, P., Grynberg, D., Noël, X., Joassin, F., Hanak, C., Verbanck, P., & ... Philippot, P. (2011). The 'Reading the Mind in the Eyes' test as a new way to explore complex emotions decoding in alcohol dependence. Psychiatry Research, 190(2-3), 375-378. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2011.06.015