Motivation

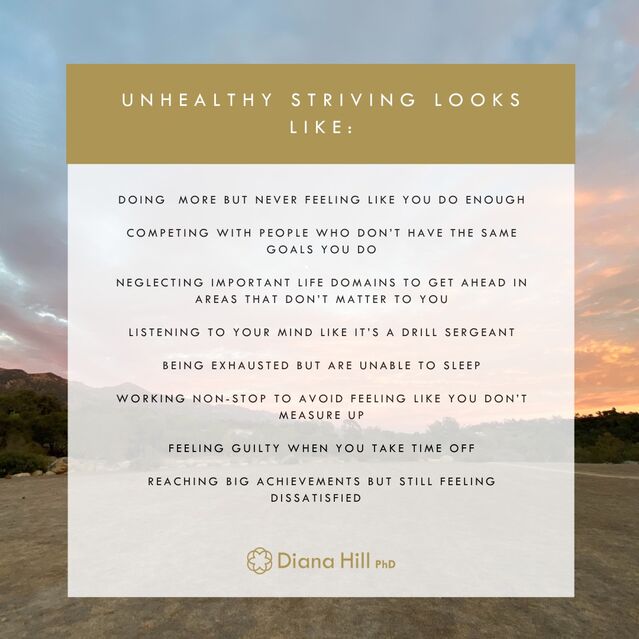

Signs of Unhealthy Striving

Use your brain’s drive mode to shift to a compassionate, values-based drive.

Posted October 12, 2021 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- We naturally strive for more; the brain evolved to have a drive system that seeks resources, shelter, food, and a mate.

- Unhealthy striving involves battling with the present moment and trying to get somewhere other than where we are.

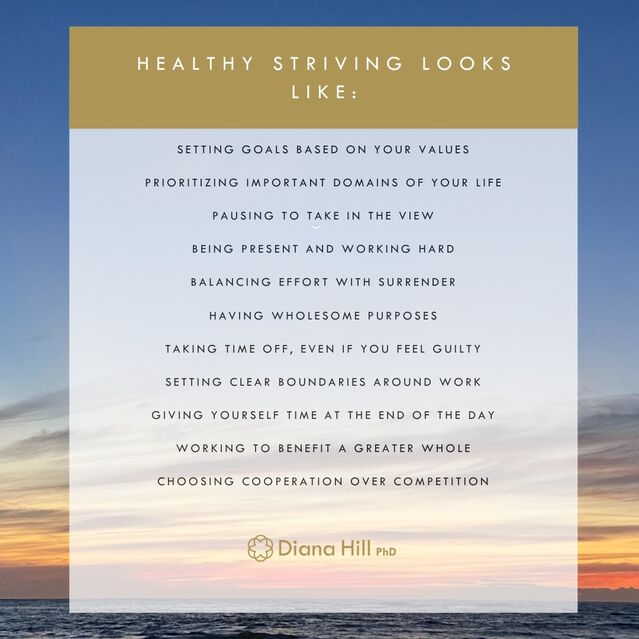

- To combat unhealthy striving, ground yourself in the present, orient towards your values, and take action that helps the greater good.

I don’t know when the cycle of unhealthy striving started for me, but I do know what happens when I get caught in it. I end up feeling depleted and empty, despite achieving outwardly impressive goals. I’ve gotten better at spotting my unhealthy striving cycle over the years and see the telltale signs. Do these look familiar to you?

The word "strive" comes from the old French word "estrif," which means to compete or battle. When we are engaging in unhealthy striving we:

- Battle with the present moment—try to get somewhere other than where we are

- Battle with ourselves—try to be someone other than who we are

It makes sense that we strive. Our brains evolved to have a drive system that seeks resources, shelter, food, and a mate. The reward pathways associated with striving are old and powerful. Yet, when this drive system is used to avoid uncomfortable feelings or pursue goals that lack meaning, we can end up in achievement cycles that leave us feeling dissatisfied and exhausted.

Unhook from this modern day Samsara by shifting your brain’s drive mode toward a more compassionate, values-based drive. Ground yourself in the present, orient towards your values, and take actions that help the greater good.

If you are interested in learning more about the striving cycle and strategies to strive better, listen to my recent talks and meditations here.