Psychology

Why Comedians Are Actually Master Psychologists

What it takes to deliver a good joke.

Posted June 11, 2018

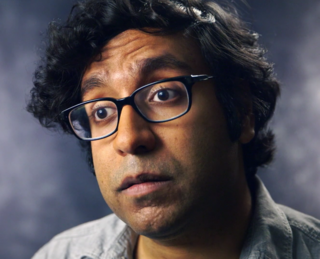

Comedian Hari Kondabolu

Malcolm Gladwell recently gave an interview with organizational psychologist Adam Grant. The topic of the conversation was work life and human behavior. "We're both in jobs that have a pretty strong monopoly on that,” Grant notes, “between journalism and social science. I'm curious, outside of our jobs, what you would say is the occupation that has the most insight into human nature and human behavior?” Gladwell offers what he calls the obvious choice: teachers. He provides an argument for his position. Then Grant gives his side, “My instinct was comedians. I think as a comedian you have to understand not only what will make people laugh but also what is right on the edge of making people uncomfortable. And that requires a lot of insight into the immediate reactions your audience is going to have. And so I think comedians are master psychologists.”

“Oh,” responds Gladwell, “I totally disagree.”

Gladwell proceeds to explain why comedians are not, in fact, master psychologists:

"Think about this Adam... The thing that's difficult about the teacher is that the teacher is dealing with people in a natural environment in real time. And there is an infinite variety in the circumstances and the kinds of people they have to interact with. The comedian, by contrast, is dealing with people in a tightly controlled setting with a rich set of expectations governing their behavior where they get to turn down the lights, dose everyone with alcohol, you know, and create an expectation that laughter is the appropriate response to what they're doing. I cannot imagine a better set of circumstances—an easier set of circumstances for navigating a social situation than those.”

After further deliberation from both sides, Grant asks, “And so you don't think that still requires deep insight into human behavior or psychology?” “Not deep insight,” Gladwell replies. “Talking to drunk people requires some insight.” Grant has no rebuttal to this. Gladwell wins the argument, hands down.

But here’s the thing: he’s totally wrong about comedians. They really do have to be master psychologists. Though not necessarily for the reason Grant supplies.

To understand why that’s the case, we have to understand a bit about what a joke is. Jokes have been the subject of scholarly analysis at least since Aristotle. In his Rhetoric, Aristotle suggests that a good joke relies on creating an expectation and then violating it. Philosophers, psychologists, and linguists have refined this notion over the years. But for the most part it comes down to this idea of expectation violation.

There is a prominent theory of humor in linguistics called the “script-based semantic theory of humor.” The theory was outlined by a professor of linguistics named Victor Raskin in 1985. The central idea of the theory is the script. In psychology, a script is a series of standard and expected actions. For example, if you go to a restaurant, there is a well-established script: sit down, order food, eat food, pay, leave. In linguistics, it’s approximately the same idea but focused on how particular words elicit expectations for those series of actions. For example, the word doctor elicits its own elaborate script. Raskin’s theory says that the way a joke work is that is sets up a particular script. Then when the punchline comes it turns the conclusion of the script on its head. Here’s an example:

“What’s the best thing about Switzerland?”

“I don’t know, but the flag’s a big plus.”

The first line sets up an expectation. The usual answers to that question, according to our conventional script, might involve chocolate or watches or mountains. So the answer at first comes as nonsensical. It violates your expectation. But then you resolve the incongruity by realizing that the answer does make sense in its own way—Switzerland’s flag is a big plus. The joke isn't funny. But it is based on the same strategy that good comedians use to execute jokes that elicit a laugh.

The reason that they need to be master psychologists to tell funny jokes is that anticipating what someone’s script is going to be for a given situation requires you to have a deep understanding about the way they see the world. And comedians fully understand this. Jeff Foxsworthy’s jokes aren't going to land with the same crowd that a Hari Kondabolu joke will land with. That’s why Foxsworthy records his specials in Texas and Kondabolu records his in Seattle. People see the world differently in Texas than they do in Seattle. A joke isn’t just unconditionally funny, no matter who is hearing it. The funniness of a joke is a function of someone's worldview. An audience laughs at a comedian’s jokes because her jokes resonate with the way they see the world.

Think about how this compares with what a psychologist does. An experimental psychologist’s job is to test hypotheses about the way people see the world—whether it’s the perspective of a single person, or the psychological tendencies of a population. And in order to do that, generally, they run experiments. These experiments will, in theory, help to confirm or deny the psychology’s preexisting theories.

Comedians actually go through a similar process. When comedians develop a new joke, they're uncertain about how well it's going to go over. But they start with a hypothesis that it will do well. And to test their hypotheses, they run their own kind of experiment. If they tell the joke and people laugh, then they know they’ve hit on something. But if they tell the joke and it falls flat, then they know they’re off-base. And once they developed a repertoire of this tested material—say, enough for an hour-long special—they know they are onto something significant. In many ways, that’s the same for psychologists, too. No single experiment solves can give all the answers about a problem. Psychologists need to develop an entire body of work in order to make progress in their field.

Think about the difference in the feedback cycle between psychology experiments and comedy experiments. The psychologist has to come up with a hypothesis and a study to test it, run the study, analyze the data, go through the peer-review process to publish it in a trade journal, then wait and see what their colleagues say. That feedback process can take years. But the feedback for the comedian, by contrast, is immediate. She tells a joke, and the audience either laughs or they don’t.

The comedian’s understanding of people, then, has a dimension of immediacy that the psychologists doesn’t. The value of the psychologist’s work is, in part, the deliberative and rigorous process that her work has to go through. But it’s also the drawback to her work. At no point does she actually have to validate it against a group of people who are out in the world just living their lives naturally, like a comedian does. Talking to drunk people may only require some insight. But building a catalogue of jokes that fit snuggly into the worldview of an audience takes quite a bit more.

References

Revisionist History. (2018). Bonus: Malcolm Gladwell Debates Adam Grant.