Psychiatry

The Case for Electroconvulsive Therapy: One Patient's Story

A young patient's courageous experience with psychiatry's oldest treatment.

Posted September 9, 2019

After months of me trying to help this patient, a cure I had hoped to bring [via psychotherapy] had not been achieved at all. Instead, a harsh, drastic, mechanical shock machine, rather than a warm, understanding human relationship, had been necessary to relieve her acute suffering…" – Ronald R. Fieve, M.D., Moodswing, 1975

Ronald Fieve's quote above, from his national bestseller Moodswing, describes a seminal event early in his career. While completing his psychiatry training at Harvard's teaching hospital in the 1950s, he was confronted with a challenging case: a lady with extreme manic-depressive mood swings wholly unresponsive to psychotherapy, the primary weapon in the psychiatric armamentarium at the time. Fieve's supervisor recommended electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), and, after a series of treatments, the patient's symptoms abated. Witnessing this rapid improvement, Fieve began his gradual shift from Freudian-minded psychoanalyst to biological psychiatrist and world-renowned psychopharmacologist.

Fieve's experience reminds me of a similar event in my own career. A female patient in her 20s came to my office for psychotherapy a few years ago. After a month of weekly sessions, I diagnosed a bipolar illness, as the patient oscillated between months of profound depression and shorter periods of elation, impulsivity, and high productivity. The patient's family history was significant for serious mental illness, and the patient's mother had been hospitalized numerous times for acute exacerbations of bipolar disorder.

I promptly referred the patient to a psychiatrist for pharmacological treatment in addition to psychotherapy. A couple of years—and more than 20 psychiatric medications later—the patient was no better. She would demonstrate some slight improvement with a particular medication but soon returned to a vicious cycle of manic highs and crippling depressive lows.

Among the drugs prescribed were the antidepressants Zoloft, Lexapro, Effexor, and Wellbutrin; the mood stabilizer Lamictal; the atypical antipsychotics Geodon, Latuda, and Vraylar; the anxiolytics Klonopin and Ativan; and the stimulants Ritalin and Strattera. Interestingly, but not surprisingly, the patient was never offered a trial of lithium carbonate, the "gold standard" in the treatment of bipolar disease. (I have written elsewhere on the underuse of lithium due to, among other factors, pharmaceutical company marketing of other, more profitable drugs for bipolar disorder.) Meanwhile, the patient gained about 90 lbs. and experienced other disturbing side effects as a result of prolonged antipsychotic treatment.

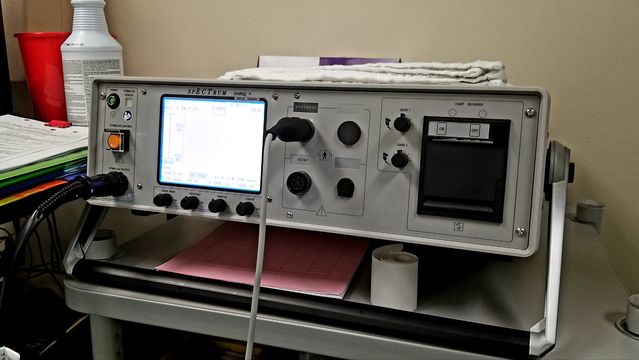

Having been trained at a university hospital with an active and well-established electroconvulsive therapy program, I began to consider the appropriateness of this treatment for my patient. She had failed multiple trials of medications and, given her severe side effects, she expressed interest in other possible options. I referred her to a well-respected psychiatrist in the community who performs ECT at a local hospital.

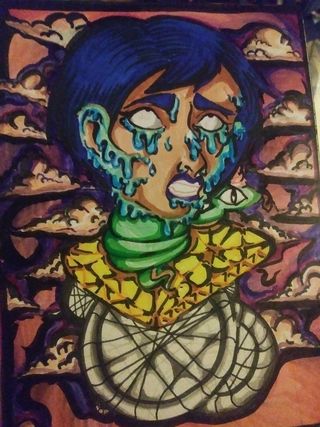

After a thorough evaluation, the psychiatrist determined that the patient was a good candidate for ECT and scheduled her for the procedure. A series of about eight treatments was performed. The patient initially complained of some problems with her short-term memory, though these abated over the course of a couple of weeks. She experienced a near-immediate improvement in her mood state and reported continued improvement in the weeks and months following the initial treatment course. For the first time in years, the patient was stable, happy, and productive. She demonstrated remarkable resilience to negative life events. Off of all medications, she began losing weight and her acne began to clear. She started to feel more confident and satisfied with life. A talented artist, her creativity returned. In her own words, she was back to her old self.

After years of psychotherapy and pharmacological therapy, neither treatment could provide this patient relief from her debilitating psychiatric symptoms. It was only electroconvulsive therapy, one of the oldest treatments in modern psychiatry, that offered meaningful and lasting change. The patient continues to receive maintenance ECT treatments—once a month or every other month—to sustain her remarkable improvement.

Electroconvulsive therapy remains the single most effective—and widely misunderstood—treatment in all of psychiatry. It is particularly effective for treatment-resistant cases of major depression, bipolar mania, and catatonic syndromes, and it has been effectively utilized in other serious, treatment-resistant mental disorders. Its inaccurate portrayal in movies such as One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest has contributed to its controversial reputation amongst the general public.

However, good evidence suggests that electroconvulsive therapy is actually underutilized and should be considered earlier in the treatment course for many patients with severe illness. For instance, a study by Wilkinson and colleagues published in Psychiatric Services in 2018 found that less than 1% of patients with treatment-resistant depression receive ECT, even though response rates are between 50% and 70% for such patients. Only one in ten hospitals that provide inpatient psychiatric care even have the capacity to provide ECT (Wilkinson, Agbese, Leslie, & Rosenheck, 2018).

My patient's story, while not unique, reveals a few important lessons. First, it took me—a psychotherapist—to suggest an evaluation for convulsive therapy. Her previous psychiatrists apparently did not consider such an option, despite its well-established efficacy in treatment-resistant mood disorder. Thus, it is important for mental health professionals of all disciplines, including those trained primarily in psychotherapy and psychoanalysis, to be well-informed of the variety of treatment options available at our disposal.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, it is likely that my patient's condition would have continued to deteriorate without ECT treatment. Should convulsive therapy been presented to this young lady earlier in the treatment course? Perhaps after the failure of two or three trials of mood-stabilizing or antipsychotic medication? Could her illness have been stabilized earlier and her long-term prognosis improved as a result of early treatment success? Could her severe side effects have been avoided? There is good reason to believe that the answer to all of these questions is yes.

Electroconvulsive therapy remains one of the most controversial and misunderstood procedures in all of medicine. Yet, for individuals like my patient, it represents the only remedy for severe, unrelenting psychiatric symptoms. Perhaps it is time for all of us, in society and in our profession, to reconsider the merits of modern psychiatry's oldest and most efficacious treatment.

Author's note: I would like to thank my patient for graciously and courageously allowing me to share her story, and her artwork, publicly.

References

Wilkinson, S. T., Agbese, E., Leslie, D. L., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2018). Identifying recipients of electroconvulsive therapy: Data from privately insured Americans. Psychiatric Services, 69(5), 542-548.