Psychiatry

Are Psychiatric Diagnoses Meaningless? Not So Fast

Discounting the importance of diagnosis ignores history and clinical reality.

Posted July 20, 2019 Reviewed by Devon Frye

A recent English study published in the journal Psychiatry Research concluded that psychiatric diagnoses are scientifically worthless and that the DSM system represents a "disingenuous categorical system." The article was picked up by several medical news outlets and stirred up controversy regarding the validity of psychiatry as a whole.

One of the authors of the study, Peter Kinderman of the University of Liverpool, went on to imply that psychiatry doesn't deal with "real illnesses" and that the philosophical basis for psychiatry is fundamentally flawed. Lead author Kate Allsopp, also of the University of Liverpool, contended that psychiatric diagnosis discounts the patient's life history and experiences. Last year, Ronald Pies and I responded to these arguments, which have been echoed ad nauseum by critics of psychiatry for years, in our piece for Psychology Today, found here.

Needless to say, a thorough philosophical investigation of the meaning of disease reveals that psychiatric disorders meet all of the established criteria for classification as bona fide medical disease. Arguments to the contrary are usually based on a faulty interpretation of history (as it applies to the meaning of disease in pathology), fail to take into account the role of suffering and impairment in disease classification, and ignore the abundance of research showing that mental illnesses are associated with specific structural and functional abnormalities in the brain.

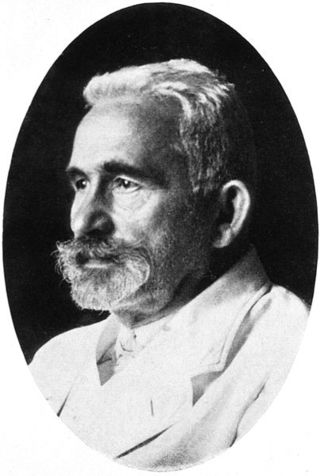

Attempts to classify mental disorders predate the modern era of psychiatry, but it is Emil Kraepelin, the pioneering German psychiatrist, who is responsible for developing the foundations for the modern psychiatric classification system. In the late 1800s, Kraepelin distinguished between dementia praecox and manic-depressive psychosis—a distinction now known as the Kraepelinian dichotomy—which remains enshrined to this day in the DSM as the difference between schizophrenia and bipolar disease.

Since Kraepelin, a number of scholars have made their own contributions to psychiatric nosology spanning the past 120 years. While some critics contend that diagnosis is a recent "invention" of psychiatry for the purpose of categorizing and stigmatizing people, experts in psychopathology have long recognized the need to classify the various types of mental disease. A diagnostic system enables research, guides treatment, informs patients, and allows for communication between providers.

Whatever the authors of the English study mean when they say that psychiatric diagnoses are "scientifically meaningless," one thing is clear: They are not clinically meaningless.

Case in point: A young woman presents to an outpatient office suffering from a profound and debilitating depression. Once an optimistic and lively person, she has been completely devoid of energy in recent weeks, unable to get out of bed, has stopped caring for herself, and has now been thinking of suicide. Wisely, the clinician assesses for past episodes of elevated mood, and the patient reveals that several months ago she was "completely on top of the world," feeling "better than well," partying, having lots of sex, spending lots of money, and didn't need to sleep for a week. The likely diagnosis is bipolar disorder, an endogenous and genetic condition, and one that is quite treatable with lithium carbonate or other mood stabilizing medication. Without a diagnostic distinction between bipolar and unipolar depression, this young lady would have likely been inappropriately treated and her long-term prognosis would have suffered.

Another case: A middle aged man presents to the psychiatric emergency room with extreme psychotic excitement and then develops a fever, muscle rigidity, and exhaustion. The patient becomes mute and begins staring into space. The diagnosis is malignant, or lethal, catatonia and warrants immediate psychiatric-critical care. Left untreated, the patient is likely to succumb to death. Early treatment with benzodiazepines and electroconvulsive therapy is paramount. Without a diagnostic concept of "catatonia" (or, in this case, its most severe variant, malignant catatonia), this individual might not survive. Diagnosis in this case is far from "meaningless."

While it may be easy for those secluded in the ivory tower of research and teaching to discount the need to classify mental disorder, it becomes virtually impossible to do so when faced with the clinical realities of the psychiatric emergency room and work with the severely and persistently mentally ill. Concepts such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression have existed for thousands of years and descriptions of these diseases predate the founding of psychiatry as a field of study. Far from an "illusion," these diagnoses represent real diseases and provide clinically useful and relevant information to both patients and doctors.

Before critics of psychiatry promote scrapping psychiatric diagnosis as a whole, they ought to consider that the current system represents an accumulation of knowledge derived over the past century and a half by the some of the greatest minds in our field. Diagnosis is not a mere attempt to stigmatize and control people, or to ignore their experiences, but rather an activity necessary for the proper understanding and treatment of mental disease. In some cases, it is lifesaving.