Education

How Schools Thwart Passions

Pursuit of passions requires time for play and self-directed education.

Posted November 25, 2018 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Follow your passions. That’s what almost every commencement speaker says to the new graduates. It’s almost cruel. If all you’ve been doing is school and school-like stuff, how do you have any idea what your passions might be or how to follow them? To find and follow your passions you need lots of time and freedom to play. Play, almost by definition, is following your passions. But we’ve pretty much removed play from young people’s lives.

Over the past several decades, we’ve continuously increased the amount of time that children spend at school, on homework, and at school-like activities outside of school. We’ve turned childhood into a time of résumé building. You don’t build passions by building a résumé trying to impress other people. You build passions by doing what you love, regardless of what others think.

It’s no surprise that people who are famous for their passionate achievements have often declared their dislike or even hatred of school. For quotes about schooling from 50 such people, see here.

Wounded by School

Some years ago, Kirsten Olson, who was then a Harvard graduate student, began to conduct research on the ways that highly successful people were inspired by their experiences at school. She hoped to document how passions were kindled by school. But her early findings led her to turn that thesis around by 180 degrees. The book that eventually came out of that work is entitled Wounded by School. [For my review of the book, see here.] Here is a quotation from the book’s forward, written by her thesis advisor Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot:

"In her first foray into the field--in-depth interviews with an award-winning architect, a distinguished professor, a gifted writer, a marketing executive--Olson expected to hear stories of joyful and productive learning…. Instead, she discovered the shadows of pain, disappointment, even cynicism in their vivid recollections of schooling. Instead of the light she expected, she found darkness. And their stories did not merely refer to old wounds now healed; they recalled deeply embedded wounds that still bruised and ached, wounds that still compromised and distorted their sense of themselves as persons and professionals."

Since the time when Olson’s respondents would have been in school, school has become even more oppressive. Recess has been reduced or removed. Creative activities have been largely removed from the curriculum. Homework has been increased. All in the name of improving scores on multiple-choice, one-right-answer standardized tests. The results of all this are not surprising. Research has shown that over these same decades, creative thinking has declined at all grade levels (here); and anxiety, depression, and suicide among young people have increased (here and here). A 2014 survey by the American Psychological Association found that teenagers were the most stressed-out people in America, and 83% of them attributed their stress to school (here). These are not conditions that promote the development of passionate interests.

My Brother Fred

Now I’m going to switch to something happier and tell you about my youngest brother Fred Carlson. His last name is different from mine because he has a different father. Fred is 12 years younger than me, so he started first grade in public school the same year I started college. He lasted there through fourth grade. Around that time my mother became something of a hippie and moved onto a Vermont commune with my younger brothers. Fred left public school then and attended a little free school, which my mother helped to start. The school had no imposed curriculum and he could do there whatever he wished.

That school wasn’t certified as a high school, however, so, at age 14, he enrolled in 9th grade at the local public school. On his second day there the principal told him, “We don’t like you hippie types around here.” So he left and never went back. Then, with no school, he hung around the commune for a couple of years and helped to build a house. He got interested in wood and carpentry. He also got interested in music and learned to play guitar and banjo.

When he was 16 he enrolled in a publicly supported program designed for high-school dropouts. The guy who ran the program asked him what he’d like to do, and he said, “I’d like to build a banjo.” Nobody there knew anything about instrument building, but the head of the program helped Fred find a local person, a guy named Ken, who had a woodworking shop and knew some things about banjo building. And so, with Ken’s help, Fred built a banjo. After that, Fred used the small sum of money that his father had saved for his education to take a 6-week course at a guitar-building school and to purchase the equipment he needed to set up his own shop. The rest is history.

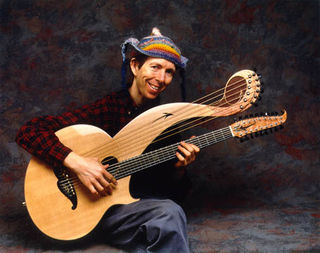

By the time Fred was 21 years old, one of his beautiful guitars was on display at the Smithsonian Museum. Ever since then he’s continued to make one instrument after another, each one different from any of the others; each one a new invention. He is famous among luthiers for his artistry, creativity, and craftsmanship. (For one example, see the inserted photo; for other examples, see here.) Fred believes, and so do I, that if he had stayed in school he would never have found his passion.

Self-Directed Education as the Pursuit of Passions

I’ve spent part of my academic career researching the outcomes of Self-Directed Education—that is, outcomes for people who did not go to a curriculum-based school, but, instead, educated themselves by pursuing their own interests. These include, many years ago, a study of the graduates of the Sudbury Valley School, in Massachusetts, where students, from age 4 on through late teenage years, are free all day to pursue their own interests; and, more recently, a study of grown unschoolers (see here and here). Unschoolers are people who for legal purposes are homeschoolers, but are not bound by a curriculum and are continuously free to pursue their own interests. The most interesting finding, for our concern now, is that a high percentage of these young adults were pursuing careers that were direct extensions of passionate interests they had developed as children in play. Here are a few examples:

- A girl who loved to play with boats went on, as a teenager, to apprentice herself to a ship captain and then became captain, herself, of a cruise ship.

- Another young girl played with dolls, as many girls do. Then she started making doll clothes; then clothes for herself and her friends. At the time of our study, she was head of a pattern-making department in the high-fashion dress industry.

- A boy was passionate about all kinds of constructive play. He would make whole villages and factories, to scale, out of modeling clay. As a teenager, he’d hang around local garages and learn about automobile mechanics by asking and watching. At the time of the study, he was a much sought-after machinist and inventor.

- Another child fell in love with science fiction. Through that, he discovered mathematics and became passionate about it. He went on to become a math professor.

- Another individual was obsessed with computers as a teenager. At the time of the study he was 22 years old and founder and head of a very successful software development company.

- A girl fell in love with circuses when she was 3 years old and began training to become a performer at age 5. By the time she was a teenager she was performing professionally as a trapeze artist, and from age 19-24 she and her best friend founded and ran their own contemporary circus company.

- A boy became passionate about making YouTube videos with friends at age 11. In his teens, he began to study filmmaking. His experience and passion led him to be hired, at age 18, as a production assistant by a major film company. At age 20, at the time of the survey, he was working with a famous director in Los Angeles on the production of a major film.

- A boy by age 15 was pursuing three passionate interests—wilderness hiking, paragliding, and photography. At age 21, at the time of the survey, he was successfully pursuing a career as an aerial wilderness photographer, combining all three of his passions.

- A girl who had previously been in a traditional school revolted, at age 13, and left school never to return. She then developed passionate interests in art, revolutions, and wildlife. At the time of the survey, at age 28, she was a full-time Greenpeace activist, fundraiser, and manager.

These are just some of the many examples documented in my research. All of these people were able to discover and pursue their passions because they had left, or had never enrolled in, a curriculum-based school.

More recently I asked some of my unschooling friends about their young children’s passions. Here are three examples of what I learned:

- Kerry McDonald’s daughter Molly has several passionate interests, one of which is baking. When someone asked her, when she was 9 or 10 years old, what she wanted to be when she grew up, she replied: “A baker, but I already am one." One thing I’ve learned is that people on the Self-Directed Education path don’t divide life into a period of preparing for the future followed by a period of living that future. They don’t distinguish between learning and living or learning and doing. That’s true when they are children and it’s still true when they are adults.

- Molly’s younger brother Jack is heavily into photography. He particularly admires and emulates the work of the famous landscape photographer Ansel Adams. I’ve attached one of Jack’s artistic photographs, called “reflections.”

- Akilah Richards’s daughter Marley has a beautiful voice and is deeply into voice acting. By age 13 she already had gigs providing the voice for animations and fan fiction audios. Her voice acting has also led her to learn Japanese because some of the works she most enjoys were produced in Japan. By age 14 she was tutoring another young person in Japanese.

The great advantage that these young people have in life is this: They are not going to school.

So, How Does School Thwart Passions?

It’s almost too obvious. Schools thwart passions by:

- Requiring everyone to do the same things at the same time. It’s not possible for all the children in a room to be passionately interested in the same thing at the same time.

- Replacing intrinsic motivation with extrinsic motivators, such as grades and trophies. To pursue a passion you have to focus on what YOU want to do, not try to impress others or win honors.

- Threatening students with failure or embarrassment, which generates fear. Fear freezes the mind into rigid ways of thinking and negates the possibility of passionate interest.

- Teaching that there is one right answer to every question, or one right way to do what you are supposed to do. That’s a surefire way to nip any possible emerging interest in the bud.

- Teaching children that learning is work and that play, at best, is just a break from learning. But anyone involved in a passionate interest knows that play and learning and work are one and the same.

So, in conclusion, if we want our children to grow up with passionate interests, we must find alternatives to school. Or, at least, we must reduce the role of school and school-like activities in their lives and increase greatly their opportunities to discover and do what they like to do—that is, to play.

This post is a somewhat modified version of the transcript of a TEDx talk I delivered.

And now, what has been your experience with finding and pursuing a passionate interest? Are you one of the lucky ones whose career is a manifestation of passion and play? How did you discover that passion? This blog is, in part, a forum for discussion. Your questions, thoughts, stories, and opinions are treated respectfully by me and other readers, regardless of the degree to which we agree or disagree. Psychology Today no longer accepts comments on this site, but you can comment by going to my Facebook profile, where you will see a link to this post. If you don't see this post at the top of my timeline, just put the title of the post into the search option (click on the three-dot icon at the top of the timeline and then on the search icon that appears in the menu) and it will come up. By following me on Facebook you can comment on all of my posts and see others' comments. The discussion is often very interesting.