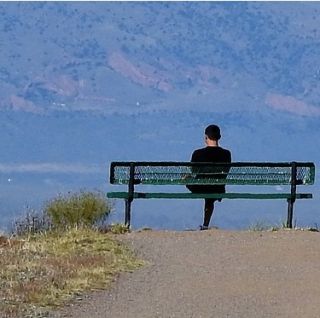

Loneliness

New Research Dispels 3 Myths About Loneliness

Debunking misconceptions about loneliness and people who feel the loneliest.

Posted May 30, 2023 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- We all feel lonely from time to time, but for some people, these feelings are severe and chronic.

- Loneliness occurs frequently during life transitions and is experienced even by those with many connections.

- Loneliness reduces the motivation to relate, and thus creates a vicious cycle of disconnection and isolation.

What is loneliness? What triggers it? And what are some myths and misconceptions about it?

To answer these questions, I present a selective summary of a recent paper on coping with loneliness, by Shrum and colleagues.

What do we mean by loneliness?

Loneliness refers to an unpleasant experience associated with the feeling that one does not belong or has unsatisfactory intimate relationships.

Unlike social isolation, loneliness is a subjective state. So, loneliness can occur even if one is surrounded by people all the time (at home, in public, at work) if he or she does not feel with them.

We may cope with loneliness in a variety of healthy and unhealthy ways—reaching out to others, participating in social activities, shopping, drug use, etc.

Pathological versus normal loneliness

It is important to note that transient feelings of isolation and abandonment (e.g., during the COVID-19 lockdowns) are common and often not a cause for concern.

The same cannot be said about severe or chronic loneliness, which is associated with negative social and health outcomes, such as low self-esteem, emotion regulation difficulties, fear of missing out (FOMO), acute and chronic pain, heart disease, and drug abuse.

This is particularly alarming due to the high prevalence of severe loneliness and social isolation. To illustrate, one in five Americans report never or rarely feeling close to others.

Loneliness triggers

Loneliness, whether transient or chronic, can occur for a variety of reasons, many of which are related to life transitions or other events that significantly affect relationships.

Some examples of such events are residential relocation, changing schools, starting a new job, getting married, going to college, the death of a loved one (e.g., parent, spouse, best friend, pet), getting divorced, migrating to a new country, and social crises (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic).

Demographic and situational factors, like living alone or being chronically rejected and bullied, are also related to loneliness and mental illness.

Now, having reviewed the meaning and triggers of loneliness, let us discuss common myths about loneliness.

Myth 1: The main cause of loneliness is a lack of relationships.

This assumption is incorrect. It is not so much a lack of relationships but the absence of quality social connections that is associated with loneliness.

In fact, research shows that to prevent feelings of loneliness, one need not be part of a large social circle or spend much time with others. If one is able to establish and maintain just a couple of healthy and intimate relationships, that may be sufficient to meet the need for love, esteem, and belonging.

Myth 2: It is mostly older folks who experience loneliness.

Loneliness is a problem for older individuals, but the problem has been exaggerated.

This misconception is understandable. After all, older people are more likely to be exposed to stressful life transitions and other triggers of loneliness, such as retirement, widowhood, or moving to a nursing home.

Nevertheless, research suggests the relationship between loneliness and age is weak. Only the very old (i.e. those over age 85) experience significantly more loneliness than the general population.

In fact, children and younger adults, compared to people over 65 but younger than 85, feel just as alone or more so.

Research indicates a significant percentage of young individuals report having no friends at all, and 30% of Millennials report feeling lonely either often or always.

Myth 3: Only social misfits are lonely.

Think of the prototypical lonely person. It is likely that you are imagining someone whose inability to fit in or belong is related to internal factors. Two examples are:

- Personality. Being neurotic, depressed, hostile, introverted, shy, socially anxious, etc.

- Absence of valued characteristics. Lacking strength, intelligence, beauty, social skills, competence, etc.

While it is true that loneliness correlates with personality traits and other internal factors, the causal direction is far from clear.

For instance, previous studies have demonstrated that people experimentally induced to feel lonely report experiencing more negative emotions (fear, anxiety, anger) and less positive mood, self-esteem, optimism, and social support.

Simply put, just as social misfits are more likely to feel alone, loneliness may also create social misfits—individuals who feel they are not wanted, accepted, understood, or valued by others or society at large.

Psychological causes of loneliness and potential treatments

Let us look at some possible causes of loneliness.

Lonely individuals tend to have maladaptive cognitions about themselves, others, and social interactions. For example, they…

- think of themselves as unattractive, unlovable, inferior, and incompetent; and also believe these shortcomings are the reason they are friendless and feel lonely.

- perceive others in the same negative way they see themselves—as unworthy of trust, unsupportive, unfriendly, etc.

- expect to be evaluated negatively (e.g., criticized, mocked, rejected) during social interactions.

Such negative perceptions lower the motivation to reestablish intimate bonds, which is necessary to reduce loneliness. The result? A vicious cycle of increasing social isolation, loneliness, and even ill health.

The good news is that there are a number of interventions to reduce loneliness. In particular:

- Personal and group psychotherapy, with an emphasis on correcting maladaptive cognitions (e.g., “everybody is untrustworthy” vs. “some people are honest and reliable”), learning flexible thinking and social skills, and finding one’s purpose in life.

- Increasing opportunities for socializing; these may involve community programs, social hobbies, recreational pursuits, online social support groups, pet adoption, etc.