Mindfulness

How-To: Mindfulness-Based Interoceptive Exposure For Pain

A 5-step evidence-based approach lowers pain, depression, anxiety, and stress.

Posted November 7, 2017

There is a growing body of research showing that for some patients with chronic pain, mindfulness-based approaches can be an effective tool in the pain management toolbox (e.g. Zeidan, et al., 2010; Cayoun et al., 2017). There are numerous studies demonstrating the burden of chronic pain, offering support for brain-based mechanisms and non-opioid mechanisms of action for mindfulness-based pain relief, reviewed in Psychology Today in detail (e.g. Bergland, Haseltine).

With that in mind, I want to share this straightforward mindfulness-based technique for reducing chronic pain. Using it can't replace proper evaluation and treatment and I recommend that anyone experiencing chronic pain consult with an appropriate clinician who specializes in pain management for a full evaluation before beginning any specific course of treatment. The approach described below is provided by Cayoun and colleagues (2017) as part of a pilot study suggesting that it may be helpful for some people suffering from chronic pain. Mindfulness-based interoceptive exposure task (MIET) may be useful when added to a comprehensive pain management program.

In their study, the sought to test a straightforward approach easy enough for almost anyone to use. Based on desensitization from traditional cognitive behavior approaches, combined with practicing equanimity in response to inner bodily cues, MIET instructs the user to attend to inner cues and "learn not to take pain personally," after an "egolessness" (anatta) approach they detail in their paper. The qualities of inner bodily sensation (interoception) they use in MIET are drawn from Theravada, comprising mass, motion, temperature, and cohesiveness. In doing MIET, the user mindfully attends to the quality of pain along these dimensions and then distances her- or himself from the experience of pain.

In their study, they worked with 15 subjects ranging in age from 26 to 73 with clinically-significant pain referred by local pain specialists, primary care providers, and psychiatrists. In order to be included, participants had to have received a medical diagnosis of chronic pain and had to agree not to seek other treatments during the study. In addition, participants were excluded if they were self-medicating with alcohol or illicit drugs, were abusing prescribed pain medication, had practiced mindfulness meditation in the past, or were unable to participate due to pain or pain treatment.

Diagnoses included: chronic pain (general), chronic back pain, fibromyalgia, arthritis, post-surgical pain, post-injury or accident pain, spinal disk damage, whiplash, and migraine headaches. Participants tended to have co-morbid conditions including anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder, which tend to go along with chronic pain conditions. Measures used throughout the study included the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21), Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS)-20, short form of the McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), and the severity scale of the Mindfulness-based Interoceptive Signature Scale—Pain Version (MISS-PV).

They were taught the MIET in person using the following protocol:

"Participants were then guided through the mindfulness-based interoceptive exposure task (MIET), which served as a guided demonstration of the task and a baseline measure of pain-related equanimity, i.e., a measure of their initial ability to allow their perceived pain to decrease as a function of equanimity. They were instructed to close their eyes and focus neutral attention on the most intense pain sensation felt at that moment and monitor the potential changes that may take place in four fundamental interoceptive characteristics (mass, temperature, motion, and fluidity/cohesiveness), in a way that is commonly implemented in MiCBT [mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy] to prevent identifying with one’s interoceptive experience, promote equanimity, and prevent the learned aversive response."

Participants were given written instructions to use at home. They practice MIET for two weeks for a short time each day and completed measures as noted above to track changes in pain, mood, and anxiety. Researchers assessed participants at two weeks and two months after and found that the majority had continued to use the MIET during the follow-up period, often in response to episodic pain.

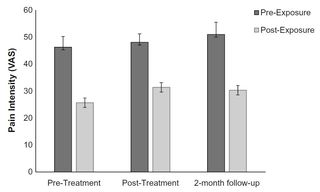

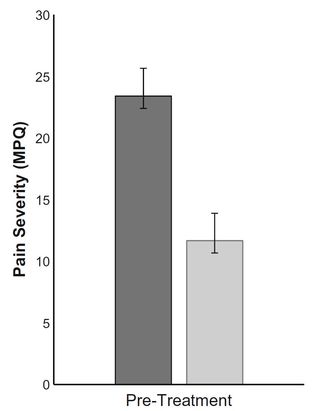

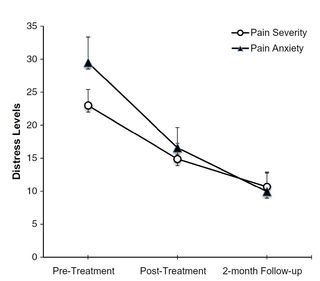

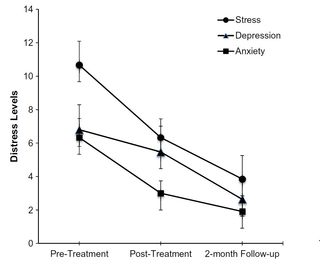

They found that participants reported significantly decreased pain severity, decreased anxiety regarding pain, and decreased anxiety, stress, and depression over the course of the study and during follow up, as follows:

While additional research is required to see if the MIET will be useful for a larger group of people and for whom it will work best, given its simplicity as an adjunctive approach to pain management and the difficulty people with chronic pain have finding relief, I'm happy to offer this preliminary work for consideration.

Here is the task used in the study:

Mindfulness-based Interoceptive Exposure Task

Below are instructions to assist you in applying the skill when pain intensifies.

You will need to practice this attention exercise in daily life every time pain sensations are prominent, for a period of about 30 seconds. Here are the instructions:

1. Locate the part in the body in which the sensation is the most intense

2. Focus all your attention at the centre of the most intense area

3. Immediately, begin to perceive what the sensation is composed of, in terms of its four basic characteristics:

a. Mass (is it light, heavy, neutral?)

b. Temperature (is it cold, warm, hot, neutral?)

c. Motion (does it move? Slow or fast? Is it immobile?

d. Cohesiveness (is it dense, solid, constricted? or is it loose,

diffused?)4. While you monitor these basic characteristics, try not to identify with the sensation and perceive it just as a physical event that is impermanent, knowing that sensations always change.

5. As much as you can, learn to accept the sensation, instead of resenting it and reacting to it emotionally. Try to prevent any emotional reaction while remaining aware of it.

References

Zeidan, F., Gordon, N. S., Merchant, J., Goolkasian, P. (2010). The effects of brief mindfulness meditation training on experimentally induced pain. Journal of Pain, March, 11(2): 199-209. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.07.015

Cayoun, B., Simmons, A., Shires, A. (2017). Immediate and Lasting Chronic Pain Reduction Following a Brief

Self-Implemented Mindfulness-Based Interoceptive Exposure Task: a Pilot Study. Mindfulness, published online October 3.

DOI 10.1007/s12671-017-0823-x