Spirituality

When Therapy Makes Things Worse, Pt. 1

Getting comfortable with our discomfort

Posted March 25, 2019

Therapy is often touted as a ‘safe place’, when, in fact, it is anything but that. It is a place where we surface our demons, dig deep into our neuroses, explore our habit patterns and challenge belief systems that often do more harm than good. Therapy is a place where we learn to be uncomfortable with ourselves, so we can, ultimately, become more comfortable with who we are and our place in the world.

We Don’t ‘Get Better’

The spiritual teacher Ram Dass is often quoted as saying that, after 40 years of psychotherapy and meditation (for those unfamiliar, Richard Alpert (Ram Dass) is himself a clinical psychologist and former Harvard professor), he is no less neurotic than he’s ever been—now, he simply invites his neuroses over for tea. This statement is a bellwether for those of us doing ‘the work’, in that it intones exactly what happens through the process of self-examination. We don’t ‘get better’. We diminish the charge of our struggle, reframe it and use what we’ve learned to make less destructive—and, in some cases, more productive—choices.

Before that happens, however, we need to sit in our sh*t—confronting our demons, digging in the dirt and deconstructing those repeated patterns of thought and behavior that seemingly and inexhaustibly dog our relationships, careers, family interactions and, often, every other aspect of our lives from finances to self-care. There is nothing to predict what prompts us to make this choice. It might be a bad breakup, the loss of a job, grief around a loved one or the simple existential realization that something just isn’t quite right with our world. No matter what the motivation, the call to self-examination is a powerful one and, more often than not, heeding that call can, at least for a time, make matters worse.

Shedding Light in the Dark

We all have skeletons. Life sometimes opens the door on that closet, amplifying the power those pesky little fellows have over us. For instance, a reflexive tendency to people please might, in the context of new relationships, turn the corner into unhealthy co-dependence, or unmet needs may, over time, build resentments that express themselves, if not as misplaced temper tantrums, at least in uncharacteristic acting out.

This leaves us with a choice—we can stay stuck in our struggle, or we can turn inward and explore our own inner darkness—our shadow self. Should we choose the latter, we will find that, just like a child who learns without a nightlight there’s nothing to be afraid of in the dark, entering the tomb of our inner landscape can, ultimately, only shed light on our darkness. In making the choice to turn inward and enter the tomb, we also choose to first recognize, and then embrace, our vulnerabilities, imperfections and, sometimes, flat out forays into Crazy Town. That’s when things get interesting and, more often than not, more than a bit messy. It’s also where ‘the work’ happens.

Becoming a Witness

One of the most important tools in this process is developing something called ‘witness consciousness’. This is a state of natural presence—operative word here being presence—where we objectively observe our thoughts and actions. It is not a state of disaffectation or emotional absence—quite the opposite. Witness consciousness is a relaxing back into an awareness of what is happening for us—in our bodies, with our thoughts and with our emotions. It is the lever that prods us into our discomfort and prompts us to see what it is we’re actually up to, and a window into our rapprochement—the way we are in the world. That window overlooks a landscape that leads to myriad paths tracking back to everything from our attachment issues to the shaping of our worldview. With the revelation of that perspective, we quickly discover we aren’t in Kansas anymore.

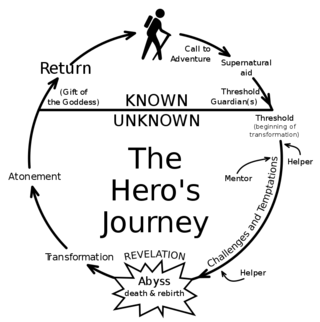

This revelation is very much a reflection of what, in literature, folklore and narratology (the study of narrative and narrative structure) has come to be called ‘The Hero’s Journey’. It is the bridge between our challenges and transformation, and the light we shed in the tomb of our inner landscape. In that abyss, we have the opportunity to discover our true nature; what in post-modern spiritual practice has come to be called our ‘authentic self’, and, in Buddhist psychology, our ‘awakened heart’.

Embracing Change

Truth be told, we’re going to fight it. Whether we’re talking about a story arc or real life, the revelation of the authentic self means change, and change is hard, to say the least. We’re going to push back—and hard. Shedding the mortal coil of our daily burdens, and coming to terms with our true nature, is probably one of the most significant, dangerous and enlightening choices we can make, but it does not come easily. Shedding that mortal coil is, in some ways, like a shedding, not of a skin, but the armor of what we feel is our humanity, which, in truth, is our isolating sensibility of separateness.

In the space between our challenges and our transformation, we encounter, not only the ego-self—the separate self we believe ourselves to be—and the authentic or awakened self, but the shadow-self. Engaging the shadow-self, and the energies it brings to our lives, we are presented with an opportunity for an integration of these disparate elements of self. The tomb becomes a womb—a sacred space where we experience the death of the former and the birth of new, entering into the light of our transformed, whole and integrated self.

The Hero’s Journey is not for the faint of heart, and many turn back on their path. For those willing to stay the course, braving the perils of our own inner the landscape and embracing the change we so fear, there dawns not only a new day, but a new way of being in the world.

© 2019 Michael J. Formica, All Rights Reserved