Race and Ethnicity

Why It Can Be So Hard to Talk About Race

When you can’t talk about a problem, you can’t solve it.

Updated June 9, 2024 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Addressing race-related issues is essential for progress, yet many are taught to avoid discussing it.

- Speaking against injustice and taking action against racism requires learning to see the world differently.

- Individuals can confront their own resistance to change, contributing to a more just society.

- Courageous conversations are needed to change old patterns.

by Monnica Williams, Ph.D., and Sonya Faber, Ph.D., MBA

When it comes to talking about race, there's a big difference between the way white families and black families approach the subject. Studies have found that white children are typically taught from a young age not to discuss race—that it's something taboo, something we shouldn't talk about (Eveland and Nathanson, 2020; Hagerman, 2017). But the truth is, ignoring the problem of race doesn't make it go away. It only reinforces existing systems of racial inequality.

On the other hand, black families don't have the luxury of ignoring race. They know that their children will be profiled and treated differently from others, often as early as preschool. They understand that talking about race is not only necessary but also empowering, as it allows them to understand and navigate the world around them.

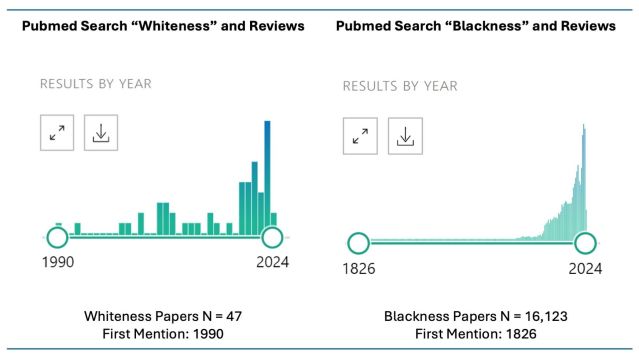

It's not that white people are bad or racist. It's just that they are socialized not to notice these problems. Most have been taught to see the world in a certain way, and that way doesn't include an understanding of the ways that racism and bias cause harm. White people are taught not to see the racism that is right in front of them daily. This also means that the psychology of race is under-represented in the academic literature (Roberts and colleagues, 2020). After all, editors and reviewers can’t cogently read or critique a topic that is too uncomfortable to discuss or even think about. When journal papers about race get published, editors and publishers often change the language to make the material more comfortable for white people, which can change the meaning and prevent authentic dialogue about race.

Please Don’t Make Me Feel Bad!

White people socialized into Western culture generally don’t acknowledge how race has shaped their lives. They have a great deal of difficulty talking about their race and what that identity means—about themselves or their racial group in general. When pressed to discuss race, they often experience a dissociative reaction (not a clinical term) requiring them to change the subject or become defensive to ground themselves and escape from the indescribable distress caused by focusing on their privileged racial identity (for example, DiAngelo, 2012).

These conversations are distressing and the state of Florida has passed a law (Stop Woke Act) designed to curtail discussions about race that might make white people feel remorse, some would argue in violation of free speech. In several places, the legislation states that: “A person should not be instructed that he or she must feel guilt, anguish, or other forms of psychological distress for actions, in which he or she played no part, committed in the past by other members of the same race or sex.” The problem with this statement is that many white people very easily feel these emotions, whether or not anyone says they “must.” This is because they have materially benefited from harm to people of color, whether it was harm done by themselves, harm done by their parents, or harm done by others in their group. The incorrectness of these benefits creates cognitive dissonance; this knowledge must be suppressed to maintain the illusion that one bears no responsibility for the benefits they accrue due to being white (Kinouani, 2020). This is why white people can be triggered by discussions about their race. They are engaged in constant mental work to blind themselves to their unfair advantages—to the point where they are unaware this mental work is happening at all. It is unsettling to have this process interrupted by being asked to reflect upon racial inequities, and so people often react emotionally (DiAngelo, 2012).

In terms of the Florida law, there is nothing wrong with the language of the act described above. Although it would be natural for fair-minded people to have some emotional response to injustice, it would certainly be wrong to state that someone must feel any particular emotion at all. The point to be made here is that the language of the act supports white fragility. Rather than learning how to engage in a conversation about racial injustice, it screams, “I am just too emotionally fragile to have this discussion.” Or worse, “Officer, arrest that person; they made me feel bad.” Avoiding things that make us anxious only reinforces those anxieties.

A Shift in Your Vision

The good news is that people can learn to see the world differently and master difficult emotions about race. Anyone can learn to recognize structural injustice and then learn to have cogent conversations to address it. It is not easy, and it won't happen overnight. But it's worth it. Because when we start seeing the world as it is, we can start having the dialogue needed to make it a better place for everyone. We can give language to distressing thoughts and make decisions based on knowledge rather than simply reacting to feelings of guilt, anguish, or distress. We can argue for what we believe in without fear.

The Need for Courageous Conversations

What do we do to change these patterns? How can one start talking about race in a meaningful way? One way is through exercises that allow you to uncover your blindness and resistance to change. Most people think they can push against racism when they see it, and they are surprised when they find themselves rendered mute. Our latest paper in the American Psychologist outlines 10 exercises designed to change the way people think and act in response to racism. The exercises help people understand unjust social norms and challenge their own biases, to ultimately learn the skills and mindset they need to have courageous conversations about race and racism.

Resist the Current by Learning to See

Personal growth on the journey of racial allyship requires one to understand and resist the quiet tide of racism. This demands a deeper look into the undercurrents that shape our society—where unseen assumptions dictate our perceptions which in turn contribute to persistent inequalities. These hidden forces are embedded in the fabric of our collective mindset, which influences what we say and how we say it. Being able to just talk about race is the first step towards unraveling a mindset that creates mental blindness and perpetuates the fears that keep us stuck in old patterns resistant to change.

References

Williams, M. T., Faber, S. C., Nepton, A., & Ching, T. (2023). Racial justice allyship requires civil courage: Behavioral prescription for moral growth and change. American Psychologist, 78(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000940

Hagerman, M. A. (2017). White racial socialization: Progressive fathers on raising 'Antiracist' children. Journal of Marriage & Family, 79(1), 60-74. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12325

Eveland, W. P., Jr., & Nathanson, A. I. (2020). Contexts for family talk about racism: Historical, dyadic, and geographic. Journal of Family Communication, 20(4), 267–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2020.1790563

DiAngelo, R. (2012). Chapter 10: What Makes Racism So Hard for Whites to See? Counterpoints, 398, 167–189. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42981490

Roberts, S. O., Bareket-Shavit, C., Dollins, F. A., Goldie, P. D., & Mortenson, E. (2020). Racial inequality in psychological research: Trends of the past and recommendations for the future. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(6), 1295-1309. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620927709

Kinouani, G. (2020). Difference, whiteness and the group analytic matrix: An integrated formulation. Group Analysis., 53(1), 60–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0533316419883455