Career

Struggling to Learn Something Hard? You're Not Alone.

A new book shows how even famous artists overcome challenges.

Posted June 1, 2024 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Key points

- Artists struggle, even the best of them.

- Artists--whether painters, playwrights, authors, choreographers--find their own methods to make art.

- A remarkable new book shows how artists create something from nothing.

As a “fiction-writer-in-training,” I’m in the midst and muck of learning how to put a story together and am amazed at the number of balls I have to keep in motion. I tell myself it’s so hard because I’m new to this, I’m still learning and I haven’t figured out the routine, the formula, and the patterns. I want to become more efficient, quit going through fits and start, and just find a smooth, streamlined way to go forward. But I hit snags, over and over. This happens most often when I am searching for something I wrote earlier and happen upon scads of outlines, structures, premise statements, character descriptions, timelines for action, family trees and scribbled thoughts and notes. Jibberish, nonsense, and a complete mess.

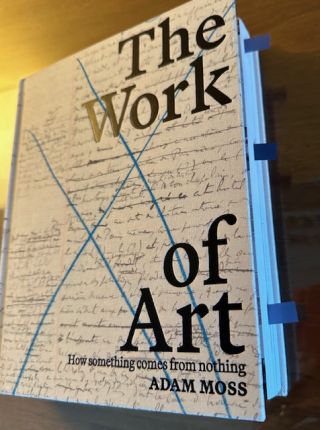

Then I found Adam Moss’s remarkable book, The Work of Art, in which he talked to 43 artists (writers, painters, dancers, playwrights and more) to find out how they think: “Where do they begin, and what do they do next, and when do they know they are finished? And more crucially, what do they do when they lose faith? Do they lose faith?” Those questions reminded me that brilliant artists are normal people.

Moss’s interviews show how artists struggle and how they encounter patterns of start/stop/change/return and whatever else happens during a creative process.

For example, Michael Cunningham, author of The Hours, changed the beginning, the characters, and the flow more than once. Poet Louise Gluck scribbles and plays with words and phrases and then circles ones that may have promise. And choreographer Twyla Tharp developed methods and processes that work for her, but may not for others. One is “the scroll,” a sheet of paper (14 feet long x 2 feet wide) that rests on the floor of her studio. On it, she jots “rough ideas,” sketches, and tracks the timing of a dance piece. Moss said the squiggles looked like hieroglyphics to him but Tharp knew exactly what each mark meant. At one point, she mentioned she had four and a half to five hours of a dance and would return to “edit it.” I’d never thought about editing in dance but it makes sense, just like editing words.

I knew intellectually that famous artists and writers struggle at times, but the end products always seem so perfect so I forget about what probably went into it. Moss’s book shows that struggle in living color. My takeaway: there’s hope for the rest of us mortals.

Finally, to the question of not losing faith and continuing to work, Tharp at age 82 came through again. In an article about her in The New York Times, she said “I keep working because I keep learning.” Good advice at any age.

References

Moss, A. (2024). The Work of Art. New York: Penguin Press.