Neuroscience

The Power of the Written Word

The written word reveals much about the nature of consciousness and the brain.

Posted December 21, 2023 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Stimuli can activate "conscious contents" in the "conscious field."

- The everyday stimulus of the written word can reliably and insuppressibly activate two conscious contents.

- How words activate conscious contents reveals much about the nature of consciousness and the brain.

The conscious field encompasses everything that one is aware of, and is experiencing, at one moment in time. For example, right now, as I am typing, I am aware of my computer, the smell of coffee, and the sound of birds outside my window, among other things (e.g., kinesthetic sensations). Each thing one is conscious of, at one moment in time, is a conscious content. The conscious field is composed of all the concurrently activated conscious contents.

Stimuli often activate conscious contents, such as memories. When discussing this with my lab, the question arose: Can one single stimulus reliably activate, not one, but two separate conscious contents? Right away we started designing possible experiments to investigate this possibility. We considered a laboratory study in which a single stimulus (e.g., an abstract shape) could, after some training that occurred earlier in the laboratory, activate two separate conscious contents (e.g., an olfactory memory and a visual memory). The idea was that subjects could learn to associate a stimulus with two conscious experiences and then, after enough training, the stimulus by itself could activate these associations. As an experimenter, one becomes accustomed to thinking in terms of “experimental manipulations” and “control conditions” in order to test some hypothesis. But a few days after the discussion, I realized that no such experiment is necessary, as there already exists a stimulus that reliably and insuppressibly activates two different kinds of conscious content: the written word. It sure is a “super stimulus.”

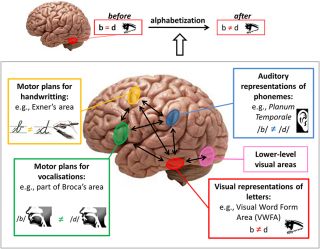

When one is presented with a written word (HOUSE), one cannot help but read it. Reading the word is no trivial process. It involves (at the least) activating visual centers in the brain, such that one can identify, say, the font in which the word is written, and involves activating the phonological representation of the word, which is an auditory-based mental representation associated with auditory areas of the brain (e.g., the superior temporal sulcus). Thus, a single written word can reliably and insuppressibly activate two different kinds of mental representations (one based on vision and one on audition), involving different brain areas and yielding two separate conscious contents, each of which is activated insuppressibly.

Words also activate meaning. These “semantic” representations might differ more among individuals than the lower-level visual and auditory representations activated by a written word. Thus, experimentally, this would make it difficult to know exactly what was activated, meaning-wise, in a subject presented with the word BIRTHDAY, for example. But the visual representation and phonological representation are more likely to be similar across subjects. Importantly, such activations are “high-level” and insuppressible, and result from years and years of extensive training. (Reading is not natural or inborn.) What makes this effect even more striking is that the association between the sound of a word (e.g., /haus/) and how it is written (e.g., HOUSE) is arbitrary and based only on convention. And we have so many of these mappings. The average college student has over 40,000 of these mappings between written words (an "orthograph") and their phonologies, and this is counting only one language. This mapping, and the resulting insuppressible activations in consciousness, are an incredible feat of the human brain. It is hard to think of any other animal that can store in its knowledge centers 50,000 such arbitrary mappings, not to mention the many more mappings that exist outside of reading, such as between objects and their names, which, too, involves an arbitrary mapping (the same object has different names across languages).

The lab and I were surprised that the most impressive experimental effect, one with far-reaching implications, is one that happens all the time in everyday life. What’s more, no laboratory experiment can ever involve a training session that is as elaborate and extensive as that for learning how to read. (Other interesting cases are musical notation and simple arithmetic.) This skill requires extensive training, but after the training, everything becomes automatic and almost effortless. The skill then elicits conscious contents, reliably and insuppressibly. Reading reveals so much about how conscious contents are usually activated by external stimuli (see further discussion here). My lab and I did need to recruit any subjects to study this interesting effect. It is occurring all the time, for free. For now, I leave you with this. Please do not read the following phrase: HAPPY HOLIDAYS.