Neuroscience

Can Projective Geometry Help Explain Consciousness?

Researchers from around the globe have gathered to discuss new ideas.

Posted April 7, 2022 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Scientists from around the globe have come together to discuss the nature of consciousness (see article here), which remains one of the greatest mysteries in science. The discussion took place in the peer commentary journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences.

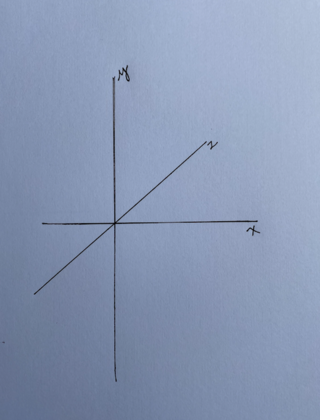

It contained an idea I had never heard about before. It struck me that, in the long run, this idea, originally introduced by Rudrauf et al. (2017), may help answer several questions about the nature of consciousness. Here is my attempt to explain this interesting and counterintuitive idea, which is based on a type of mathematics called “projective geometry.” Projective geometry was used by Renaissance painters to create the illusion of depth in their paintings.

Our “conscious field” is composed of everything we are conscious of at one moment in time. For example, one could be resting on a beach and be conscious of a ship on the horizon, the feeling of sand under one’s feet, and the smell of, say, pineapple juice. The conscious field includes the perceptual world we experience at every moment. Regarding our visual sense, notice that the conscious field has three dimensions: one horizontal (the horizon seen from the beach), one vertical (which allows one to see the clouds above the horizon), and one that involves depth (a sand toy near one versus a ship that is far away). According to “viewpoint theory,” which, again, is based on the principles of projective geometry, for something to observe these three dimensions (as we do), the origin of the vantage point must reside outside these three dimensions.

Hence, the observer must exist in an extra dimension, which would be, in our case, a fourth spatial dimension. It is proposed that this observer cannot ever directly observe itself, because observing the fourth dimension would then require an additional, fifth spatial dimension. This is called the “n + 1” problem: To apprehend an n number of dimensions, the observer must be in the n + 1 dimension. Viewpoint theory explains an observation noticed by the philosophers Hume and Schopenhauer: That the conscious observer cannot directly apprehend, nor introspect about, itself. It perceives only other things, such as percepts, urges, and ideas.

In the present article by Merker et al., it is further argued that this principle applies not only to perception but also to the imagination and dream world: One cannot even imagine the nature of a fourth spatial dimension. Our conscious field, and its model of the world, are incapable of representing this dimension in which, in a sense, the conscious observer resides. The conscious observer is not able to directly introspect about itself.

I find it easier to understand this idea by thinking of a simpler case. Imagine that one lived in a two-dimensional world, such as that of a line drawing on a sheet of paper. The line drawing is of a tree. If one lived on the paper, that is, on the planes of this two-dimensional world, one would not ever be able to see the whole drawing on the page. It is only from the third spatial dimension, outside the plane of the two dimensions composing the drawing, that one could see the tree. Similarly, to perceive the three spatial dimensions of our perceptual model of the world, the observer must reside in a fourth spatial dimension, which cannot be perceived in any way. This approach may illuminate much about the nature of consciousness.

For a humorous tale by Morsella, involving a neurologist, by Morsella, click here.

References

Rudrauf, D., Bennequin, D., Granic, I., Landini, G., Friston, K., & Williford, K. (2017). A mathematical model of embodied consciousness. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 428, 106–131.