Sleep

What's All That Stuff They Put on Me During a Sleep Study?

Wires and tape and EMGs...oh my!

Posted August 26, 2014

Have you ever had a sleep study done?

Perhaps you or a loved one has been referred to a sleep clinic for insomnia, apnea, narcolepsy, or restless legs syndrome. Maybe you’ve participated in a sleep research study. Or perhaps you're just looking for your next Halloween costume.

The hallmark of getting a sleep study done is—well, looking something like this (left).

Looks rather scary, right? Fear not—each component has a very simple purpose.

The snore mic is the first piece of equipment we’ll put on the sleep research participants in our lab. It’s simply a sensor I tape over the hollow of the participant’s throat that lets us know whether they’re snoring. This is interesting to note, especially for what our laboratory studies, because snoring may indicate obstructive sleep apnea—cessation of breathing due to some sort of blockage.

Next, I’ll apply two sticky pads attached to wires (one on the chest and one on the lower rib). These electrodes are used in electrocardiography (EKG), allowing us to monitor heart rate and rhythm.

I’ll then place two sticky electrodes on the shins, which will detect leg movement. In research studies, this helps us determine whether the participant wakes and moves around in the middle of the night (an “arousal”); in the clinic, uncontrollable leg movements may be indicative of restless legs syndrome (RLS).

Two Velcro straps, called strain gauges, are then placed snuggly around the chest and abdomen. These monitor the rise and fall of the torso while breathing.

Then comes the fun part: head electrodes! The principle behind electroencephalography (EEG) is to measure the brain’s “electrical activity”—a simple way of describing voltage fluctuations caused by ion flow in the brain’s nerve cells (neurons).

To create a tight seal and promote conductance, I’ll first rub the scalp with an abrasive lotion, then scoop wax onto each electrode before placing them in precise locations. I’ll then cover the head in gauze to keep everything in place during sleep.

Using many electrodes means we can study electrical activity from different parts of the brain. Since each brain region shows us characteristic wave patterns, we know what stage of sleep the participant is experiencing; we even know when they’re dreaming! (But don’t worry—we don’t know what they’re dreaming about—nor do we particularly want to!)

I’ll then place a nasal cannula in the participant’s nose to measure airflow from both the nose and mouth. Studying one’s breathing using both the cannula and strain gauges is very important; if we see that the participant’s torso is rising and falling but there is no nasal airflow, this may indicate obstructive sleep apnea.

Lastly, I place an oximeter on the participant’s finger just before they go to bed. This device uses infrared light to measure the level of oxygen in the blood. “Normal” levels are between 95-99% saturation; anything lower may indicate breathing abnormalities.

Wires from all sensors and electrodes plug into a small headbox linked to an amplifier, which is connected to the computer. (Don't worry—if you have to go to the bathroom in the middle of the night, we can simply unplug the headbox and you can trudge your way to the bathroom, looking like a mix between a mummy and Medusa.)

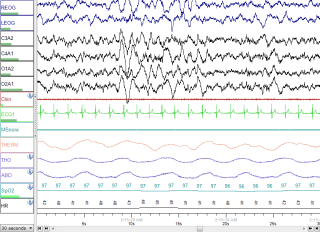

Now, what kind of information, exactly, is being projected to the computer with all these ridiculous wires? It looks a little something like this (left).

But that’s a whole new can of worms for another day. (You can read a little more about sleep cycles in this post).

Oh, and one last thing—like Santa Claus, “we see you when you’re sleeping, we know when you’re awake…” There’s a camera on you all night, so we know when you pull out that pesky cannula…and we’ll wake you up to fix it!