Addiction

Star Trek: The Mental Frontier

Can Kirk and Spock help teach psychology as no one has taught it before?

Posted September 5, 2012

Through a dozen motion pictures and more than 700 episodes over the course of five live action television series, not to mention an animated series and an endless stream of novels, comic books, and fan fiction, Star Trek characters have explored strange new worlds and the range of human nature itself. Because creator Gene Roddenberry believed in showing the essential humanity of all sentient species regardless of their planet of origin, extraterrestrial nonhumans also let us look at real psychological processes. While Star Trek explores many aspects of human nature, key issues keep reappearing, particularly those of importance to understanding and resolving conflicts between diverse peoples. Even the ongoing struggle between logic and emotion usually manifests as a cultural issue.

A course instructor interested in using Star Trek to each psychology first must consider that they cannot count on students in general to know the details of any specific episode or motion picture. If teaching a special topics course that would attract students specifically interested in Star Trek, the instructor has so many strange new worlds to explore.

Logic vs. Emotion

Each Star Trek series’ cast includes a main character who seeks to understand human emotion: Spock the Vulcan-human hybrid (Star Trek, known to fans as The Original Series - TOS); Data the android (Star Trek: The Next Generation - TNG); Odo the shapeshifter (Star Trek: Deep Space Nine - DS9); Tuvok the Vulcan and the Voyager's holographic Doctor (Star Trek: Voyager - VGR); and yet another Vulcan, T’Pol, a female for once (Star Trek: Enterprise - ENT). While the Vulcans suppress strong emotions beneath the veneer of logic, emotionless Data seeks to become more human and Odo, capable of mimicking human beings, dispassionately observes human nature with curiosity, rarely envy.

Fantasy vs. Reality

Characters often have to make choices between accepting reality or retreating into fantasy, whether through worlds filled with illusion (“The Menagerie,” “Shore Leave,” TOS), many Holodeck adventures (TNG), or Voyager’s recurring Holodeck village.

Prosocial vs. Antisocial

Distinguishing good from evil can be tricky. In “The Enemy Within,” an early TOS episode, a transporter accident splits Kirk into two people, one embodying his aggressive nature and the other nonaggressive. Aggressive Kirk is not purely evil, nor is nonaggressive Kirk an effective leader. Both sides must merge back into a single individual for Captain Kirk to use all his strengths.

“The Conscience of the King” shows that good intentions can produce actions history will deem monstrous, and that those deemed monsters might nevertheless possess the capacity for remorse. Lack of remorse and empathy largely define psychopathy (essentially evil disorder). Greater cruelty and sadism are core aspects of malignant narcissism, a more severe personality pathology that psychologist Erich Fromm called “the quintessence of evil.” Roddenberry eventually regretted that he overemphasized the Klingons' worst qualities, making them seem too evil, because he did not believe an entire race or culture could be evil. With so many Star Trek villains, anyone interested in using Star Trek to teach a psychology course would have no shortage of examples to draw from while discussing the complexities of prosocial and antisocial actions and intentions.

Conflict vs. Peacekeeping

Enterprisecaptains, who preach peaceful conflict resolution, get into a lot of fights. Relevant issues include pacifism, superordinate goals (critical to Star Trek: Voyager’s series premise), mirror image perceptions “Errand of Mercy,” “Day of the Dove”).

Security vs. Freedom

Psychologist Erich Fromm held that the basic human dilemma involves contradictory desires for both freedom and security. Star Trek emphasizes freedom to the point of distrusting restrictive security. Time and again, Kirk breaks the Prime Directive, Starfleet’s non-interference policy, in order to help or make people shake off what he sees as tyranny. Kirk’s distrust of utopian societies colors his views on both pacifism and security.

Us vs. Them

Hundreds of Star Trek episodes address how different groups view each other. Issues include prejudice, discrimination, stereotypes, outgroup homogeneity, and related attitudes. Ironically, though, Star Trek often perpetuates these kinds of thinking by presenting vastly more diversity among humans than within any extraterrestrial species.

Scientific Method

Star Trek features many scientist characters, their research projects, and discussions of scientific ethics (as in the Voyager episode, “Scientific Method”). An instructor might have difficulty linking most of the featured science to psychological research methods.

Psychophysiology

From the ridiculous TOS season three premiere, “Spock’s Brain,” to a Voyager episode in which aliens provoke prisoners’ aggression with stimulus to the brain’s hypothalamus (“The Chute”), Star Trek plot frequently rely on tampering with characters’ brains, nervous systems, neurotransmitters, and hormones, sometimes affecting everybody on the ship except for whichever character saves the day for everybody else.

Sensation and Perception

Of the physical senses, the one examined most often in Star Trek is vision, particularly its loss, as when Spock briefly goes blind (“Operation Annihilate!” TOS). Star Trek: The Generation stars a blind character, Geordi, in its regular cast. “Loud as a Whisper” (TNG) features a deaf negotiator, and many deaf actors appear in walk-on roles. Members of the Ferengi race have greater hearing than do other characters.

To demonstrate power, a Cardassian officer (played by David Warner) tries to make Captain Picard say there are three lights.

Generations: Developmental Issues

Star Trek offers outstanding opportunities for reviewing developmental psychology. Even though the Enterprise of the original series didn’t feature Starfleet crew traveling with their families as in TNG, the program often looked at developmental issues: childhood (“And the Children Shall Lead”), adolescence (“Charlie X,” “Miri,”), immaturity (“The Squire of Gothos”), parenthood (“Friday’s Child”), sex (“Amok Time,” “The Mark of Gideon,” “All Our Yesterdays”), gender (“Wolf in the Fold,” “Elaan of Troyius,” “Turnabout Intruder”), marriage (“For the World Is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky”), aging (“The Omega Glory”), senility (“The Deadly Years”), dying “For the World Is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky”), grief. (“The Man Trap”), immortality (“Metamorphosis,” “Requiem for Methuselah”).

An instructor teaching about grief must look at why Kirk doesn’t grieve over his brother’s death (“Operate: Annihilate!”). “Journey to Babel” introduces Spock’s father Sarek and their conflicted relationship. Otherwise, The Next Generation and Deep Space 9 provide better examples for family issues. A child born on The Next Generation grows up on Deep Space 9, and we see how another little girl born early in Voyager develops.

Topics worth discussing include will power (“Plato’s Stepchildren”) and how power corrupts (“Where No Man Has Gone Before,” “Plato’s Stepchildren”). This might be good place to examine why people feel motivated to administer torture (“Chains of Command” TNG) despite its general ineffectiveness. Issues on the larger scale include questions regarding why human and nonhuman characters fight, rebel, play, hoard latinum, and explore the galaxy.

Altered States

Altered states of consciousness may allow us to explore the deepest frontier of all as the subconscious mind intrudes upon the conscious. The Next Generation episode “Night Terrors” examines the mind distorting effects of dream deprivation. “The Naked Time” and “The Return of the Archons” (TOS) involve extreme examples of disinhibition.

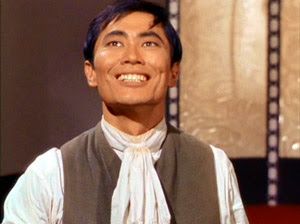

Sulu (George Takei) feels elated and disinhibited. Star Trek

Sulu (George Takei) feels elated and disinhibited.

Star Trek

Memory can be a terrible, unreliable, and precious thing. Many characters experience short-term amnesia (“The Paradise Syndrome,” TNG; “Conundrum,” “Amnesia,” TNG; “Sons of Mogh," DS9) and sometimes false memories (“Dagger of the Mind,” TOS). Amnesia typically involves retrograde memory loss in which the individual forgets the past, but Captain Archer suffers anterograde difficulty in which he cannot form new memories (“Twilight,” ENT).

Language, Psycholinguistics

Most Star Trek series skirt around issues of psycholinguistics by using universal translators that allow characters to hear others in their own respective languages. The Next Generation episode “Darmok” makes the point that simply understanding words does not inherently mean everything will make sense when people from different cultures lack each other’s historical and cultural references. Star Trek: Enterprise, which does not rely so heavily on universal translators, provides more examples of psycholinguistic issues.

Personality

We can have a lot of fun analyzing these fascinating characters in terms of specific personality theories, traits, and types. Of the human needs identified by psychologist David McClelland, the three he considered most dominant each figure prominently in the characters’ lives: Need for Achievement (NAch), Need for Power (NPow), and Need for Affiliation (NAffil). The Big Five personality factors of McCrae and Costa’s OCEAN model (openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism) provide a model for extensive personality assessment. Furthermore, do all hard-driven Starfleet captains have Type A personalities?

The original series shows little faith in artificial intelligence and offers plenty of reasons to distrust its computers and androids. The Next Generation‘s android, Lieutenant Data, is often its most sympathetic character. Voyager takes it a step further with a computer-generated character, the ship’s holographic Doctor.

Psychopathology

The 1966-1969 series rarely named any real mental illnesses, referring instead to characters going “mad” or “insane” (e.g., “City on the Edge of Forever”), and the later programs don't do a lot more. Suicide comes up (“Deathwish,” “Night Terrors,” VGR), as do assisted suicide (“Ethics,” TNG) and mass suicide (“And the Children Shall Lead,” TOS). Garek on Deep Space 9 experience long-term depression. Episodes of the original series which look at cognitive processes that, while not mental disorders in and of themselves, can be symptoms of mental illness include “The Ultimate Computer” (delusion) and “Obsession” (obsession).

In Star Trek: The Next Generation, Reginald Barclay develops Holodeck addiction (“Hollow Pursuits”), which might be comparable to modern Internet or video game addiction although the screenwriter intended his addiction as a satirical depiction of some Trekkies’ excessive preoccupation with imaginary characters. The TNG episode “The Game” more directly covers gaming addiction. In Star Trek’s most extensive exploration of substance addiction, the Vulcan T’Pol becomes hooked on an emotion suppressant throughout Star Trek: Enterprise’s third season.

Depictions of psychotherapy rarely resemble real therapeutic techniques (“Whom Gods Destroy,” TOS; “Outcast,” TNG).

Social Psychology

We could easily fill a Star Trek and Social Psychology course without focusing on another other area of psychology. The many examples of topics include the Pygmalion effect (“Mudd’s Women,” TOS 1x6), deception, hostage taking (“The Cloud Minders”), altruism, social dilemmas (“Tomorrow Is Yesterday”), belief perseverance (“The Doomsday Machine”), obedience, conformity, leadership styles, and deindividuation.

Optimism

Star Trek is an optimistic franchise, full of hope for the human race collectively and as individuals. Gene Roddenberry envisioned many struggles ahead of us and many advancements for the whole of humankind. He expected great things for the human condition. Positive psychology can make great use of Roddenberry's creations.

The Future Matters

Gene Roddenberry's science fiction franchise offers a wealth of characters and diverse situations a psychology instructor might explore to use psychology to analyze Star Trek and Star Trek to teach psychology.